For twenty years they have waited, often impatiently, thinking of when their time will come. For fifteen years they have hoped to take control of the Socialist Party (PS) whose inner workings they were already familiar with. For ten years they have thought about becoming lieutenants as a stepping stone to higher rank one day. For five years they have known the cruel charms of being in ministerial office. And now here they are, all four of them, fighting it out against each other as the main contenders in a socialist primary contest to choose a presidential candidate for 2017. A contest that feels like it could be the end of the party in every sense, even though none of them has ever given up on their dream to make it to the Elysée.

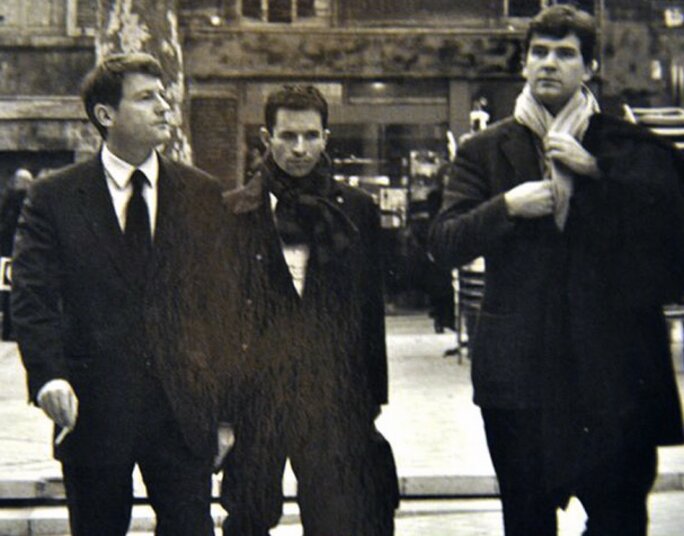

The quartet in question are former prime minister Manuel Valls, former education ministers Benoît Hamon and Vincent Peillon, and former economy minister Arnaud Montebourg. This group of politicians from the same generation who are in their 50s - with the exception of 49-year-old Hamon - know each other very well. On October 16th, 2002 at the Sorbonne in Paris, three of them launched the Nouveau Parti Socialist, a movement within the Socialist Party which had just suffered the calamity of its presidential candidate Lionel Jospin failing to reach the second round of that year's presidential election. The only one who did not take part in this attempt to breathe fresh life into the party was Manuel Valls. Though he had discussed joining this new modernising movement with the three others, he ultimately chose to stay loyal to former prime minister Jospin and the existing PS first secretary, one François Hollande.

Back in 2002 all four men were in fact seen as 'Jospin's babies', rising stars of the party who had had their first government experience under the outgoing left-wing coalition administration, either in the National Assembly or as ministers. They were already much discussed in socialist circles, often because they irritated party bosses with their maverick views and their stances on the fringe of the party as they increasingly kept their distance from the mainstream party apparatus.

Enlargement : Illustration 2

Even back in 1995, when they were in their thirties and the PS had just ended with the era of François Mitterrand, they already seemed certain of a bright future. Valls and Hamon were leaders of socialist youth organisations. Peillon and Montebourg were not party hacks in the same way but still knew their ways around the mysteries of the party of which they had been members for some years.

Philosophy graduate Vincent Peillon, for example, had been speech writer for the president of the National Assembly, Henri Emmanuelli, in 1992, before standing against the latter in 1994 to become head of the PS itself. Peillon received 8% of the vote while Emmanuelli was elected as first secretary.

Arnaud Montebourg, meanwhile, was already a lawyer in the public spotlight, famous for having defended the man who murdered French official René Bousquet, who had been accused of crimes against humanity in World War II. Montebourg also achieved fame for forcing the son of the then-prime minister Alain Juppé to move out of his Paris flat in 1995 amid allegations of an abuse of power. Flamboyant, and to some an irritant, Montebourg was already preparing to establish his political power base in the Saône-et-Loire département or county in central-eastern France, next to the Nièvre département where he was born. Montebourg was vocal in his criticism of the failings of France's Fifth Republic set up by Charles de Gaulle and hoped to inherit the mantle of Mitterrand, who back in the 1960s had likened rule under the general to that of a “permanent coup d'état”. Montebourg also aped Mitterrand's annual tradition of climbing up the Rock of Solutré in the Saône-et-Loire, by staging his own yearly walk up Mont Beuvray.

When Montebourg was elected as a Member of Parliament for Saône-et-Loire in 1997, he joined Peillon who had been elected in the Somme in northern France. The pair become something of a National Assembly political double act – they were dubbed “Modeste et Pompou” by Libération after two cartoon characters - who instigated inquiries on issues such as tax havens and used their powers to present themselves as champions of probity in public life.

Montebourg made his mark in the PS Parliamentary group while Peillon became spokesman for the PS, which was led at the time by François Hollande. Valls was employed in prime minister Lionel Jospin's office while Hamon worked for Martine Aubry, who was minister for employment and solidarity. Both were political advisors. The two men each had a network of contacts but had not yet found a local political stronghold. However, Valls later made use of his position as vice-president of the Paris region to became mayor of Évry near Paris in 2001, a post he held until 2012. Hamon drew on his contacts among young socialists and his establishment of the Nouvelle Gauche, or 'New Left', inside the PS to provide a springboard for his own ambitions in the party.

So it was that three of these four thirty-something politicians found themselves at the Sorbonne in October 2002 after the disaster of that April's presidential election, seeking to represent a revitalised Left after the failure of social democracy. The keys to the Nouveau Parti Socialiste (NPS) platform were the modernisation of French institutions and a return to policies aimed at the working classes and young people. Their stance was seen as strong criticism of a Europe that had become, in political-economic terms, too liberal.

If Valls ultimately declined to join the NPS section it was because he felt it was too far to the left and he wanted to cultivate support on the right of the party, adopting a mixture of Blairism from Britain and the authoritarian approach of the early 20th century French prime minister Georges Clemenceau. He developed policies based on his work as a local politician and set out his stall as a figure on the right of the PS. By that time Valls had already gained a reputation for a tough approach to law and order, though he retained an interest in socialist social programmes, albeit with a strong dose of pragmatism and ideological flexibility. That was also the hallmark of the trio who set up the NPS, setting them apart from the more traditional left of the PS.

Hamon had been a supporter of Michel Rocard, prime minister under Mitterrand, and later became a protégé of Martine Aubry. Peillon set out his stall as a liberal in political terms, identifying himself with the non-Marxist socialism of the end of the 19th century. Montebourg positioned himself around questions of morality and the modernisation political institutions, and in 2000 founded a movement calling for a new constitution, the Convention pour la Sixième République. These were all complementary positions but nonetheless the NPS did not fare well when it came to wielding power inside the Socialist Party. At the PS conference at Dijon in the autumn of 2003 the NPS movement picked up just 16.5% of the vote. They were faced with the master party tactician François Hollande, who was helped by an alliance with leading party figures from the Bouches-du-Rhône département the south and the Nord-Pas-de-Calais region in the north, which between them contained around a third of all party activists. Hollande was re-elected party boss with 61.5% of the vote.

This meant that the story of the NPS was over almost as soon as it had begun. Increasingly the trio went their own way, driven by disagreements on strategy and clashes of ego. Each ploughed their own furrow, a little like the fourth member of the gang, Manuel Valls, who while supporting the mainstream Hollande line also made clear his differences on the right of the party.

During the early 2000s and the constant internal battles in the PS and right up to their involvement in the government of prime minister Jean-Marc Ayrault under President Hollande from 2012 to 2014, the four were constantly forming and dissolving alliances between themselves. They seemed unable to unite and wrestle control from the generation above them that had methodically thwarted their rise. Now, at last, after waiting so long, their time has finally come.

After 2007: a time for action

Just once in the past did the four politicians all find themselves on the same side in a political fight. It was at the end of 2004 during the internal Socialist Party referendum on whether they should back the planned Constitution for the European Union. All four were for a 'no' vote but the party voted in favour by 59%. In the nationwide referendum that followed all four chose to remain quiet, as the party boss Hollande and the senior conservative politician and future president Nicolas Sarkozy made common cause in favour of the EU constitution, even appearing together on the cover of Paris-Match. The only one of the four to break ranks was Manuel Valls who a few weeks before the 2005 referendum announced he was in favour of a 'yes' vote. In the end the 'no' side won in France with 54.7% of the vote.

At the PS party conference in Le Mans that followed, the movement backed by Peillon and Hamon – both Euro MPs by now – picked up 23.6% and they decided then to back Hollande, who won again with 53.7% of the vote. But Montebourg did not join cause with them as he refused to back down on his demands for constitutional reform and a Sixth Republic. The NPS was definitively over.

As for Valls, he had supported Hollande from the start of the Le Mans conference. He then backed Ségolène Royal in the party's primary to choose a presidential candidate for 2007, a move in which he was joined by Peillon and then Montebourg, both of whom became her spokesmen. Hamon, who had wanted Hollande to stand, eventually backed former prime minister Laurent Fabius.

Enlargement : Illustration 5

After Royal's defeat to Nicolas Sarkozy in the 2007 election, Valls resisted attempts by the latter to recruit him into the conservative government. Briefly Valls and Montebourg discussed forming an alliance of 'young lions' but the idea quickly fell away. Neither was able to construct a movement around them inside the party, a problem that still dogs them today. In contrast Hamon was able to build upon his old youth networks and brought together different strands of opinion on the left of the party. Peillon continued to represent the line adopted by Ségolène Royal, and was able to count on the support of officials and elected representatives who had backed the NPS.

In 2008 the Socialist Party held a conference at Reims in northern France to choose a new leader. Hamon decided to make a bid for the leadership himself, heading a list reunifying the left wing of the party. Valls and Peillon were Royal's main supporters in her bid to be party boss while Montebourg eventually swung behind Martine Aubry. It was Aubry who won the second round vote, with the backing of Hamon, whose movement had lost in the first round. The final result was greeted with howls of outrage from Royal's supporters, with Valls and Pellon outspoken over the claims and counterclaims about cheating in the election.

Now head of the PS, Aubry made Hamon the party's chief spokesman and after a few lively debates put Montebourg, who was the national secretary for renewal, in charge of arrangements for the 2011 primary to choose the party's 2012 presidential candidate. Montebourg himself was to be a candidate in that primary, representing the left wing of the party, with Valls as standard bearer for the right. Hamon supported Aubry. The verbal jousts between Valls and Montebourg were a feature of the televised debates between the candidates.

Initially Peillon, who kept control of the movement that had backed Royal even though the pair had at one point bitterly fallen out, worked at creating a new “social, environmental and democratic” movement. However, it failed to reconstitute the left and barely survived its launch weekend. It did, though, herald the current alliance between the PS, the Parti radical de gauche (PRG) and some greens which forms what is known as the 'Belle Alliance' and which is staging the primary election. Peillon had initially backed International Monetary Fund managing director Dominique Strauss Kahn in the 2011 primary but when the latter was forced to pull out of consideration, Peillon backed François Hollande – the eventual winner.

Enlargement : Illustration 7

Valls only won 5% of the vote in the primary and as soon as his first round defeat was announced he switched his allegiance to Hollande. He then became the director of communications for the latter's presidential campaign. It was Montebourg who created the biggest surprise, picking up 18% of the first-round vote. Though he was closer to Aubry he, too, backed Hollande in the second round.

Once Hollande was in the Elysée he made all four men - Valls, Peillon, Hamon and Montebourg - ministers in prime minister Jean-Marc Ayrault's government. Valls became interior minister, Peillon was put in charge of education, Montebourg was given a remit to oversee the recovery of French industry and Hamon was responsible for the social economy and solidarity. Then in March 2014, following what was clearly a deal between the trio, Valls became prime minister with the backing of Montebourg, who was promoted to economy minister, while Hamon went to education. The loser was the existing education minister, Peillon, who left the government and withdrew from national politics. Then, five months later, Valls himself oversaw the departure of Montebourg and Hamon from the government, in a disagreement over budgets and austerity policies at European level.

Enlargement : Illustration 8

As prime minister Manuel Valls took an increasingly tough line with the left inside the party, even talking at one point about some of the left being “irreconcilable”. Little by little Valls cornered Hollande. And when the president said he was not going to stand again, the prime minister said he himself was ready to take on Montebourg at the socialist primary to choose the 2017 presidential candidate. Meanwhile Hamon had stolen a march on Montebourg by announcing his own candidacy in the summer of 2016. Then, as if it was decreed that none of the four could miss this great school yard debate that looks like an ideological settling of scores (unless it's the other way around), Vincent Peillon, too, threw his hat in the ring. This was to the great dismay of Valls who thought he would be the only candidate occupying the political space carved out by Hollande's decision not to stand.

Now the four, each of whom has shown a complete inability to step aside in favour of one of the others, and who have never learnt how to agree on things, are going to have to fight it out among themselves. All are quite good speakers, quite good-looking, come across as leaders of the gang, are a bit macho (while describing themselves as feminists) and are all to a greater or lesser extent convinced of their own destiny, along with the superiority of their intellect and/or strategy. The quartet fills the void of a party at the end of its story, like the last survivors standing amid a heap of ruins.

Vincent, Benoît, Arnaud and Manuel … you could be forgiven for thinking you were in a Socialist Party version of a film by director Claude Sautet. These promising thirty-somethings, the thwarted modernisers of former years, now battling it out against each other in their fifties, set on revenge after having to wait for so long, and in a somewhat low-key primary contest. But are they really competing for the Elysée, or are they in reality simply jostling for position in the battle for the repositioning and reordering that will take place on the Left if the Right wins the presidential election in 2017?

They are, in any case, the four favourites to wear the colours of a party that is on the road to extinction, a party whose survival they have not contributed to because they have never learnt how to play collectively. Each will doubtless make a case for the special nature of their respective manifestos. And it is true that each one today represents a section of what remains of the PS.

Benoît Hamon represents the modernised left wing, backing a universal or basic income, a social economy and a 32-hour working week; Arnaud Montebourg stands for a “producers' alliance” between bosses of small companies and unions, and a “Made in France” form of economic nationalism that is critical of the European Union; Peillon represents the left of the current government minus the authoritarianism exemplified by Manuel Valls; and Valls himself represents the left of the current government minus the lack of authority shown by Hollande.

All four have been ministers under Hollande with two of them critical of the government's record – Montebourg and Hamon – with the other two broadly accepting and supporting it. It is currently impossible to say which of them will qualify for the decisive second round of the vote; the two rounds of voting are on January 22nd and January 29th. It is also equally hard to know which of the losing first round candidates would back who in the second round. That is the appeal and uncertainty of a primary between politicians from the same generation.

But the quartet of fiftysomethings (or nearly in Hamon's case) are themselves now caught in a generational pincer movement outside the primary. On the one side is the radical left 65-year-old Jean-Luc Mélenchon, on the other side is Emmanuel Macron who is in his thirties. The former freed himself from the PS (though after 30 years in its ranks) to give him more freedom to express his left-wing views, and his candidacy for the presidency is today more attractive to a left-wing electorate put off by the socialist government and the PS. The latter, meanwhile, a former advisor to Hollande and then his economy minister, has seized his chance and is making an independent bid for the presidency, having chosen not to linger for years in the backwaters of political life.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

This is an abridged version of an article in French which can be found here.

English version by Michael Streeter