A trial is always a battle of narratives, a war of words. In the case of Nicolas Sarkozy, standing trial since January 6th on charges of corruption, criminal conspiracy, receipt of the proceeds of the misappropriation of public funds, and illegal campaign financing, all related to the alleged funding of his 2007 presidential election campaign by the regime of Libyan dictator Mummar Gaddafi, it took four of his defence lawyers five hours to offer an opposing narrative to that which the prosecution presented ten days ago.

They were speaking on the final day of the trial, on Tuesday, after the defence lawyers for the 11 others accused of various degrees of involvement in the alleged funding, including three of Sarkozy’s former ministers, had summed up their arguments over the preceding days.

The prosecutors, from the PNF financial crimes branch of the public prosecution services, have requested that Sarkozy, 70, be handed a seven-year prison sentence and a fine of 300, 000 euros, less than the maximum sentence he faces of ten years in prison and a fine of 375,000 euros. The panel of judges are due to announce their verdicts and sentencing on September 25th.

The prosecution has requested that the three former ministers – Brice Hortefeux, 66, Claude Guéant, 80, both of whom served successively under Sarkozy as interior ministers, and Éric Woerth, 69, his campaign treasurer and later labour minister – be handed jail sentences. It called for Guéant to be given a six-year prison sentence and a 100,000-euro fine, Hortefeux to be given a three-year jail sentence and a fine of 150,000 euros, and for Woerth to be sentenced to one year in prison.

The prosecutors argued that the three had joined Sarkozy in mounting an “inconceivable, extraordinary, indecent pact of corruption” with Muammar Gaddafi beginning in 2005.

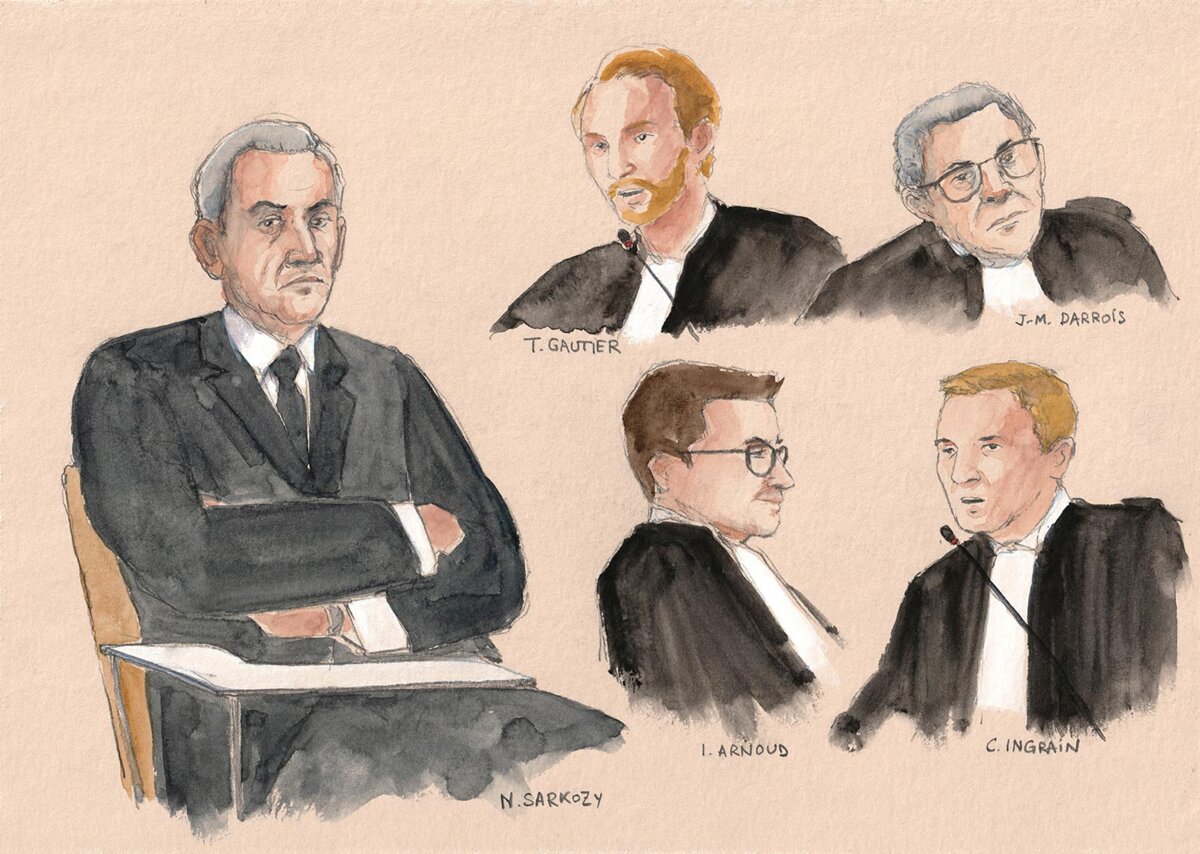

On Tuesday, in a packed courtroom, where the former president’s wife Carla Bruni-Sarkozy, his sons from an earlier marriage, Jean and Pierre, and his brother Guillaume had taken their seats, Sarkozy’s lawyers – Jean-Michel Darrois, Isaac Arnoud, Tristan Gautier and Christophe Ingrain – spent the day pleading his innocence of what they described as an “empty” case against him and asking for the charges to be thrown out.

They slammed the prosecution case for its “absence of proof”, “inexistant proof” and “crazy idea”, and what one called a “debacle of the prosecution”. The first of them to speak was Jean-Michel Darrois, who described what, to him, was the true motive of the investigating magistrates who led the judicial probe and sent Sarkozy for trial, along with the PNF. It was, he said, not led in the name of the fight to uphold probity but, rather, “to sully” the image of Nicolas Sarkozy.

Enlargement : Illustration 1

It was an attempt “to maintain the image of a dishonest Sarkozy, a gangster, greedy, with little respect for the values of the [French] republic”, the lawyer declared, as if ignoring that his client has already been convicted of “active corruption” and “influence peddling”, for which he was handed three years in prison, two of them suspended, and a three-year ban on holding public office. He was spared one year behind bars with an order to wear an electronic tag. Sarkozy is also awaiting the result of his final appeal against his conviction for illicit funding of his failed 2012 re-election bid.

Speaking in turn, and at great speed, lawyer Tristan Gautier attempted to demonstrate, using graphics projected onto a large screen, that the 5 million euros that the Gaddafi regime paid in 2006 into accounts held by French-Lebanese businessman Ziad Takieddine, who acted as a go-between in the dealings of Sarkozy’s team with Tripoli (see more here and here), could not have been linked to the alleged “corruption pact” between Sarkozy and Gaddafi as claimed by the prosecution. Instead, he argued, they were “funds“ addressed to Ziad Takieddine in payment of his activities for Libya”.

In March, prosecutor Quentin Dandoy told the court how Takieddine had withdrawn 600,000 euros in cash from funds originating indirectly from moneys provided by the Gaddafi regime. He had also sent a bank transfer of 440,000 euros to an account in the Bahamas belonging to Thierry Gaubert, a longstanding ally and friend of Sarkozy’s since the latter’s earliest years in politics, and a close friend of Hortefeux.

Gaubert, shortly before receiving the bank transfer from Takieddine, noted in his diary “Ns-Campaign”.

Under questioning during the judicial investigation, Gaubert insisted that “Ns” was not a reference to Nicolas Sarkozy, and that “Campaign” could have meant any number of things. When questioned in court, he finally claimed that the note was in fact a reference to a newspaper article he had read about Sarkozy’s future election campaign and his conservative party, the UMP.

Sarkozy’s lawyer said he had “no idea about the reason for the transfer” of Libyan money, via Takieddine’s account, to Gaubert but boldly stated that “one can formally exclude that it is linked to the [2007 presidential] campaign”. The defence also adopted the argument of campaign treasurer Éric Woerth, who claimed that the circulation of cash in large denomination notes during the campaign came in part from donations sent through the post anonymously by militants of Sarkozy’s UMP party (later renamed Les Républicains) and that other cash sums came from similarly anonymous donations handed over to the reception desk at UMP headquarters.

A telling element to observe in a lawyer’s defence speech is what they do not say, what they avoid mentioning, and Sarkozy’s defence team dodged several of the key points raised by the prosecution. These included the payments made by Libya to Ziad Takieddine after a secret meeting in Tripoli on October 1st 2005 between Sarkozy’s then chief of staff, Claude Guéant, with the second most powerful man in the Gaddafi regime, Abdullah al-Senussi, head of military intelligence, and against whom an international arrest warrant had been issued after his conviction by a Paris court of having organised the 1989 mid-air bombing over Africa of a French airliner in which 170 passengers and crew died.

For the prosecution, the regime keenly wanted to have the international arrest warrant withdrawn by France, and it was at that meeting between Guéant and Senussi in October 2005 that a “pact of corruption” was agreed. At the time, Sarkozy was interior minister and preparing to launch his bid to replace fellow conservative Jacques Chirac as France’s president in elections due in the spring of 2007. The Gaddafi regime, meanwhile, had begun seeking to normalise its relations with the West, after years of isolation as a rogue state.

In an attempt to explain having dinner with a state terrorist wanted by France, and which occurred without the French embassy in Tripoli being informed of the event, and was held without the presence of any diplomat, translator or bodyguard, but in the presence of the intermediary Ziad Takieddine, Guéant claimed the meeting was an impromptu event, a last-minute trap prepared by Takieddine into which he fell. “Claude Guéant has already given you his replies,” said lawyer Christophe Ingrain, suggesting that because it was “a sort of shame a posteriori which explains that Claude Guéant did not mention it to his minister”.

But that was to overlook, or dodge, the evidence produced by the prosecution that demonstrated there was nothing impromptu about the dinner between Senussi, Guéant and Takiedinne, nor was it a trap. Instead, the evidence suggests it had been planned in concertation between Takieddine and Guéant, the latter fully aware of what was to take place.

This concerned two documents seized as evidence during the judicial investigation and which, argued prosecutor Quentin Dandoy, proved that Guéant’s meeting with Senussi was planned well in advance and with his full knowledge.

One of the documents in question was a page of headed notepaper from the interior ministry, where Guéant was chief of staff to Nicolas Sarkozy. On the page, in Guéant’s handwriting, figured the annotations “Libya”, “Sep 22 2005 dinner with Takieddine”, and “Tripoli Oct 1st 2005”.

The second document came from Takieddine’s computer archives in which there is a note concerning a meeting he would have with Guéant on September 22nd 2005. This was entitled “visit from CG”. Among a list of “subjects to raise” was “dinner with the number 2 (head of the security and defence)” and the detail that it would be “without ambassador” but with “ZT”. It was a precise description of the circumstances in which Guéant met with Senussi one week later.

Another secret meeting with Senussi involved Brice Hortefeux, another close friend of Sarkozy’s and then a junior minister for local authorities (a post within the interior ministry), which occurred in Tripoli on December 21st 2005 and in the presence of Takieddine. These were the exact same circumstances as the meeting between Guéant and Senussi.

Hortefeux, echoing Guéant, had told the court he had fallen into a trap when he met with Senussi.

According to Sarkozy’s lawyer Christophe Ingrain, the meeting “was a whim by the regime’s number two [Senussi] who asked his friend Ziad Takieddine to organise the rendez-vous”. Concerning that meeting, Ingrain made no mention of a supposed “shame” on the part of Hortefeux as justification of why, as he claims, he did not discuss it with Sarkozy. The lawyer offered no explanation for that, but he declared that it was a “crazy idea” to link the meeting with a pact of corruption.

Sarkozy’s defence team also had no comment to offer as to why Guéant and Hortefeux continued to have close relations with Takieddine after the Tripoli meetings whereas, as they claimed in court, they had been tricked into meeting a terrorist.

The revelations of a dead man’s notebooks

The prosecution had described an extract from handwritten notes belonging to Shukri Ghanem, who was Libyan prime minister from 2003 to 2006 and subsequently oil minister from 2006 to 2011, when the Gaddafi regime was overthrown, as “fundamental” and “decisive” proof of the alleged Libyan funding of Sarkozy’s campaign.

Ghanem’s body was found floating in the River Danube in the Austrian capital Vienna in April 2012, in circumstances that remain mysterious. One year later, in an investigation unrelated to the alleged Libyan funding, Dutch police discovered a suitcase filled with belongings of Ghanem at the home of his son-in-law, in the city of Den Bosch. They included notebooks in which Ghanem jotted down details of his life, on an almost daily basis, as a Libyan dignitary and later in exile, between 2006 and 2012. The authenticity of Ghanem’s notes has been validated by Norwegian and Dutch police, before they were transferred to the French judicial investigation into the Libyan funding allegations.

The extracts produced in court concerned the transfer of Libyan funds destined for Sarkozy’s election campaign and were dated April 29th 2007, when Ghanem had a lunch meeting with Bashir Saleh, Gaddafi’s chief of staff. According to Ghanem, Saleh detailed a series of transfers of funds for Sarkozy’s campaign amounting to 6.5 million and made up of 3 million euros ordered by Saif al-Islam Muammar al-Gaddafi, Gaddafi’s second son, 2 million euros ordered by Abdullah al-Senussi, and 1.5 million euros sent by Saleh himself. Some of these amounts corresponded with movements found on Takieddine’s accounts. “Supposing [the notebooks] are authentic, that does not constitute serious and concordant evidence,” declared defence lawyer Jean-Michel Darrois, who said he did not rule out that the notebooks were falsified.

To recognise the opposite would lead to the collapse of the principal argument advanced by Nicolas Sarkozy since the first day of the trial. Namely, that the case against him is the result of a fabrication by the Gaddafi clan seeking revenge for launching in 2011 air strikes against the regime by an international coalition egged on by Sarkozy.

By avoiding the substance of the meetings with Senussi by Guéant and Hortefeux, and dodging the issue that the latter two continued their close relations with Takieddine, but also minimising the importance of the Ghanem notebook extracts, and swiftly passing over the circumstances in which Bashir Saleh – given refuge in France after the fall of the Gaddafi regime – was exfiltrated from the country shortly after Mediapart’s revelations of a Libyan document approving the election funding, Sarkozy’s defence team moved on to the core theme with which to attack the prosecution case.

“No proof, no evidence,” declared Ingrain, denouncing what he called a “whatever it takes” approach of the PFN prosecutors who “scrape the bottom of drawers” to support their arguments. “Nicolas Sarkozy didn’t need financing other than that which was official,” he said. “In 2005, he was at the height of his popularity. He was the man of power of the Right.” The suggestion he entered into a pact of corruption, the lawyer added, “is not ridiculous, it’s grotesque”.

If there was no pact of corruption, there are no diplomatic, economic or legal favours, unlike the claims of the PNF he said. The five-day visit to Paris by Gaddafi in December 2007 was nothing exceptional at the time in Europe, he suggested, and the principle of welcoming the dictator was first given the green light by Jacques Chirac, French president from 1995 to 2007. “Was there a Gaddafi travelling up the Champs-Élysées with the Republican Guard?” asked Ingrain. “Should he have been welcomed in a sub-prefecture with a cold meat buffet?” The lawyer made no mention of the role of Ziad Takieddine in organising Gaddafi’s visit, which had been recognised earlier in the trial by Guéant.

As for the economic favours, the provisional agreement reached during Gaddafi’s visit for France to sell Libya a nuclear reactor, that was also, according to the defence lawyers, an idea dating from Chirac’s presidency.

They suggested that the return favour to have the international arrest warrant for Senussi overturned also dated from Chirac’s time, and if they were pursued afterwards, notably through the involvement of Sarkozy’s close friend and lawyer Thierry Herzog, Sarkozy himself was never directly involved, claimed Ingrain.

In his summing up, Ingrain broadly suggested that Sarkozy never asked for anything, never ratified anything, never knew of anything, and never did anything, and compared the case against him with The Magic Skin by 19th-century French novelist Honoré de Balzac. “The case lies on the floor, there is no substance left.”

As Tuesday’s sitting drew to a close, Sarkozy was given the opportunity of being the last one to speak. Surprisingly and uncharacteristically, he showed little enthusiasm. “My lawyers have spoken, and spoken well,” he said, before denouncing a “detestable political and media context” and a “political and violent” summing up by the prosecution. Few words that suggested much more.

-------------------------

- The original French version of this report can be found here.

English version by Graham Tearse