The trial of Nicolas Sarkozy and 11 others on corruption charges relating to the alleged funding of the former French president’s 2007 election campaign by the regime of Libyan dictator Muammar Gaddafi is now entering its final stages, after more than two and a half months of often tense proceedings.

The former president, who turned 70 in January, is charged with corruption, criminal conspiracy, receipt of the proceeds of the misappropriation of public funds, and illegal campaign financing. Prosecutors on Thursday concluded their three days of summing up when they called for Sarkozy to be handed a seven-year prison sentence and a fine of 300, 000 euros, less than the maximum sentence he faced of ten years in prison and a fine of 375,000 euros.

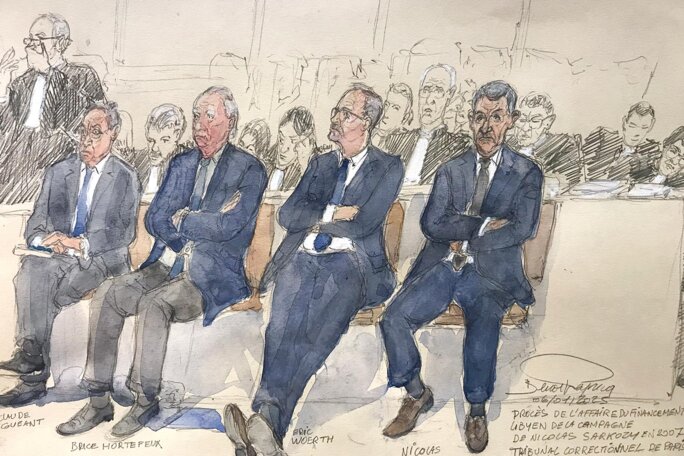

With him in the dock are three of his former ministers – Brice Hortefeux, 66, and Claude Guéant, 80, both of whom served successively under Sarkozy, as interior ministers, and Éric Woerth, 69, who served as budget and labour minister. The prosecution called for Hortefeux to be handed a three-year jail sentence and a fine of 150,000 euros, for Guéant to be given a six-year prison sentence and a 100,000-euro fine, and for Woerth to be sentenced to one year in prison.

The prosecutors said the three had joined Sarkozy in mounting an “inconceivable, extraordinary, indecent pact of corruption” with Muammar Gaddafi beginning in 2005.

Sarkozy was then interior minister and preparing to launch his bid to replace fellow conservative Jacques Chirac as France’s president in elections due in the spring of 2007. The Gaddafi regime, meanwhile, had begun seeking to normalise its relations with the West, after years of isolation as a rogue state.

Part of that process began in December 2007, seven months after Sarkozy’s election, when Gaddafi was given a lavish welcome in Paris during a five-day visit.

Sarkozy has vigorously denied the charges against him, once more telling the court last week that he had not received “one centime of illegal money, Libyan or any other”.

Following the statements on Monday of the civil parties, and the summing up of the prosecutors, who are from the financial crimes branch (PNF) of the public prosecution services, which ended Thursday, it will be the turn next Monday for the defence lawyers to present their final arguments – due to be completed by April 10th – after which the trial ends.

The verdicts, to be decided by the three trial judges at a later date, are not expected to be announced before several months.

Mediapart’s investigative reporters Fabrice Arfi and Karl Laske have been in court throughout the trial, and here they review what has emerged from the cross-examinations that ended last Thursday, in what is the most far-reaching political corruption trial ever held in France.

Enlargement : Illustration 1

The trial has led to the emergence of new evidence, as well as elements that provide a clearer context of the evidence already established.

The defence strategy of the principal accused, Nicolas Sarkozy, has, as the proceedings unfolded, revealed clear flaws which, despite his oratorical talent, the former French president could not hide. For the Libyan funding trial has also been a lively clash of facts against words.

The self-defeating argument of the defence

The trial began with a show of force by Sarkozy who, half-lion, half-orator, gave a spirited display in those early days of January when he denounced the charges against him as folly. During the hearings, and adopting the manner of the defendant-cum-lawyer that he is, Sarkozy, rather than answering questions put to him by the court, pleaded his case with “my heart and soul”, often adopting a tone of what was obvious, and on many occasions tackling cross examinations with the phrase “But that makes no sense!”.

His two principal lines of defence have been:

- The whole affair is a plot hatched by the Gaddafi regime in 2011 on the eve of the first airstrikes against it by France ahead of a NATO-led coalition;

- The prosecution case is empty and has not the least “proof” against him, despite a ten-year judicial investigation.

In court on February 10th, Sarkozy admitted that there was “serious evidence” against him but that it “is not concordant” (the criteria for placing a person under formal investigation in France, which precedes bringing charges, is that there is “serious and concordant” evidence of their involvement in a crime).

After being faced with the objective evidence of the case against him – that of secret meetings in Tripoli, the involvement of nefarious intermediaries, the return favours for the Gaddafi regime, bank transfers to and from tax havens, cash withdrawals, the use of cash in the 2007 presidential campaign, the suspicious exfiltration from France of a former dignitary of the Gaddafi regime – Sarkozy was then questioned about the far-fetched arguments advanced by two of his co-defendants, Claude Guéant and Brice Hortefeux, who figure among his close inner circle.

They claimed that the Gaddafi regime paid out funds in 2006 believing they were for the 2007 presidential campaign, but that all these secret sums were instead pocketed by the intermediary employed by Sarkozy’s staff when dealing with Arab countries, Paris-based Franco-Lebanese businessman Ziad Takieddine (see more here and here), who they said had used them in order to swindle the Libyans.

Sarkozy had already claimed the same in statements given to the pre-trial investigation. According to him, Takieddine, who he called a “little pig”, is a manipulator and a “crook” who “took advantage” of the “naivety” of Guéant and Hortefeux to cheat the Gaddafi regime.

Not only is that claim contradicted by the evidence in the case file – it is proven that Takieddine did not keep all the Libyan money for himself – but to suggest so invalidated the two principal lines of Sarkozy’s defence. For it implies the Gaddafi regime was truthful in saying in 2011 that it had paid secret funds intended to finance Sarkozy’s campaign four years earlier – but which Sarkozy argues was a lie motivated by revenge for French military involvement in overthrowing the regime.

The case file, meanwhile, is anything but empty.

The former French president spent much of his time at the stand turning on his co-defendants without pity in an attempt to save himself, just as he did during the investigations that led to the trial. To believe his testimony would be to accept that he was, before 2007, France’s least informed interior minister – and after 2007, the French president with the least competent entourage, whose activities he took little or no interest in.

It is a risky strategy of defence. As the trial unfolded, he appeared as the head of an organised group whose existence he denies. The judicial investigation’s conclusions are that the alleged crimes of his co-defendants were carried out under his authority and for his benefit.

The hearings have clearly demonstrated that his argument leaves only a tiny margin for manoeuvre for his co-accused. In order to ensure their line of defence fits in with that of Sarkozy’s, they are obliged to present the court with explanations that exceed all rationality.

Sarkozy appeared at times drunk on his oratory skills, as if having confused the courtroom with the platform of a political meeting, or with one of his many studio interviews with the primetime TV evening news. He sometimes entered into frontal confrontations: “Go on then, I’m not made of sugar,” he goaded one of the prosecution team who questioned him in a hesitant manner, like a boxer telling his opponent to hit him harder.

In contrast, the court magistrates, led by presiding judge Nathalie Gavarino, took care not to fuel the act. Instead, patiently and methodically, and without playing to the audience, they laid the bricks, one after the other, of a wall of facts.

Enlargement : Illustration 2

On January 16th, the prosecution focussed on a fundamental issue, and which was largely unreported, during the first cross-examination of Claude Guéant. He was questioned about his secret meeting, on October 1st 2005 in Tripoli, with Libyan official Abdullah al-Senussi, Gaddafi’s brother-in-law and head of the dictator’s military intelligence services. At the time, Guéant was Sarkozy’s chief of staff at the interior ministry (after Sarkozy’s election in 2007, Guéant became chief of staff of the presidential office, the Élysée Palace, and was later appointed as interior minister).

In 1999, Senussi, who was regarded as the second-highest official of the Libyan regime, had been sentenced by a Paris court in absentia to life imprisonment after he was found guilty of being the mastermind behind the 1989 bombing of a DC-10 passenger plane operated by French airline UTA. A total of 170 passengers and crew died in the mid-air explosion over Niger in West Africa. After his conviction in 1999, France issued an international warrant for Senussi’s arrest.

Relatives of the victims of the bombing have been attending Sarkozy’s trial in Paris as civil parties.

In an attempt to explain having dinner with a state terrorist wanted by France, a dinner which occurred without the French embassy in Tripoli being informed of the event, and was held without the presence of any diplomat, translator or bodyguard, but in the presence of the intermediary Ziad Takieddine, Guéant claimed the meeting was an impromptu event, a last-minute trap prepared by Takieddine which he fell into.

Already destabilized by questions put to him by presiding judge Gavarino over his account that he had told no-one about his meeting with Senussi, and that he also continued to meet with Takieddine afterwards, Guéant was next confronted by PNF prosecutor Quentin Dandoy. The latter showed two documents seized as evidence during the judicial investigation and which, he argued, proved that Guéant’s meeting with Senussi was planned well in advance and with his full knowledge.

The first of the documents in question was a page of headed notepaper from the interior ministry, where Guéant was chief of staff to the minister, Nicolas Sarkozy. On the page were, in Guéant’s handwriting, the annotations “Libya”, “Sep 22 2005 dinner with Takieddine”, and “Tripoli Oct 1st 2005”.

The second document comes from Takieddine’s computer archives in which there is a note concerning a meeting he would have with Guéant on October 22nd 2005. This was entitled “visit from CG”. Among a list of “subjects to raise” was “dinner with the number 2 (head of the security and defence)” and the detail that it would be “without ambassador” but with “ZT”. It was a precise description of the circumstances in which Guéant met with Senussi one week later.

For the prosecution, it is a crucial point. The dinner with Senussi was the first time that the subject of Libyan funding for Sarkozy’s election campaign would be raised, according to statements given by Takieddine and Senussi. For the prosecution, this was the starting point of the corruption pact entered into by the defendants and the Gaddafi regime. If the meeting with Senussi was not in fact an impromptu one as claimed by Guéant, it was instead planned hand-in-hand with Takieddine.

Enlargement : Illustration 3

The chronology of the events is revealing. On October 6th 2005, just five days after the dinner meeting between Guéant, Senussi and Takieddine, the then French interior minister Nicolas Sarkozy, travelled to Tripoli to meet with Gaddafi. The following month, on November 26th, Sarkozy’s close friend and lawyer, Thierry Herzog, travelled to Libya to discuss his proposed plan to overturn the international warrant issued for Senussi’s arrest. The month after that, Brice Hortefeux, another close friend of Sarkozy’s and then a junior minister for local authorities (a post within the interior ministry), in turn visited Tripoli, on December 21st, where he secretly met with Senussi in the presence of Takieddine, in the exact same circumstances as the meeting between Guéant and Senussi.

Taking the stand, Brice Hortefeux similarly claimed to have fallen into a trap when he met with Senussi. “I wonder if you yourself believe in what you’re saying,” retorted another PNF prosecutor, Sébastien de La Touanne.

The payments by Libya

All of which is anything but anecdotal. For in the weeks that followed the December meeting between Hortefeux and Senussi, the Gaddafi regime sent an initial bank transfer of close to 500,000 euros into the account of Takieddine’s offshore company, Rossfield Limited, without any accompanying justification. Part of that sum would subsequently be transferred on to an account in the Bahamas belonging to Thierry Gaubert, a longstanding ally and friend of Sarkozy’s since the latter’s earliest years in politics.

A man hiding in the shadows behind the Takieddine, Hortefeux and Guéant when Sarklozy was interior minister, Gaubert, shortly before receiving the bank transfer from Takieddine, wrote in his diary “Ns-Campaign”.

Under questioning during the judicial investigation, Gaubert insisted that “Ns” was not a reference to Nicolas Sarkozy, and that “Campaign” could have meant a number of things. When questioned in court, he claimed that the note was in fact a reference to a newspaper article he had read about Sarkozy’s future election campaign.

As for the Libyan money sent into his account, he has given both the investigation and trial a total of four different accounts, all of them irrational. But, taking the stand in court, Gaubert said his aim was above all to show that the funds had “no link to the presidential account”. Which, if that is really the case, a truthful account would suffice.

The court has also heard how Takieddine, before the 2007 election campaign began, withdrew a total sum in cash of 1.2 million euros from a bank account in Switzerland into which Libyan money had been placed. Some of the cash withdrawals, notably of 200,000 euros, 275,000 euros and 300,000 euros, had aroused the bank’s suspicions because of their unusual nature, noted the presiding magistrate. The prosecution argued that the withdrawals had no connection with Takieddine’s personal lifestyle, which was funded by other accounts he owned.

A revealing notebook

Another marking moment of the trial came during a hearing on February 10th. That was when Sarkozy, who had until then made a point of honour in always providing answers to questions put to him, appeared somewhat flustered before a document containing an extract of handwritten notes belonging to Shukri Ghanem, who was Libyan prime minister from 2003 to 2006 and subsequently oil minister from 2006 to 2011 before defecting when the Gaddafi regime was overthrown in 2011.

Ghanem recorded his notes of events by hand on an almost daily basis from 2006 to 2012. The notes produced in court were dated April 29th 2007, and concerned the transfer of Libyan funds destined for Sarkozy’s election campaign. These were described as transfers of 3 million euros, ordered by Saif al-Islam Muammar al-Gaddafi, Gaddafi’s second son, and 2 million euros, ordered by Abdullah al-Senussi.

Not only do these sums correspond precisely with transfers made into the bank account of Takieddine’s offshore company Rossfield Limited, but the date of when the notes were written – in April 2007 – prove that the allegations of Libyan funding of Sarkozy’s campaign could not have been invented during the 2011 war by revengeful members of the Gaddafi regime.

Sarkozy told the court that he did not “necessarily” question the “authenticity” of the document, while also saying that he had a “doubt about its veracity”. The authenticity of Ghanem’s notes has been validated by Norwegian and Dutch police in a separate investigation, and by their French colleagues in the judicial probe.

The body of Shukri Ghanem was found floating in the River Danube in the Austrian capital Vienna on April 29th 2012, in what remain mysterious circumstances.

Cash circulating during the election campaign

On March 17th, police commander Frédéric Vidal took the stand as a witness. For ten years and under the authority of two successive investigating magistrates, Vidal, from the French police’s Central Office Against Corruption and Financial Crimes, OCLCIFF, headed the groundwork of the investigations into the alleged Libyan funding of the 2007 campaign.

His concise testimony effectively shone light on the strategy of the police investigation which began as if pulling on a thread of evidence, a miniscule one at first, about the possible circulation of undeclared cash sums in large denomination notes during the 2007 campaign.

Retrospectively, it’s stupid.

Questioned about the discovery by police of the use of cash sums by the Sarkozy campaign team, such as for paying militants, the campaign treasurer, Éric Woerth, clearly had difficulty explaining their origins. Woerth, who served under Sarkozy after his election as budget minister and later labour minister, gave the judicial investigation a statement saying that part of the money came from donations sent through the post anonymously by militants of Sarkozy’s Union pour un Mouvement Populaire (UMP) party (later renamed Les Républicains). He said other cash sums came from similarly anonymous donations handed over to the reception desk at UMP headquarters. That claim was refuted by UMP staff.

“If you wish, we could also talk about the colour of the envelopes,” Woerth haughtily declared at a hearing on February 13th, visibly exasperated by presiding judge Gavarino's insistent questions over the presence of the cash.

As for Claude Guéant, he denied using a vast strongroom he had rented from a bank during the campaign for hiding cash. Guéant said it was instead for the purpose of storing documents, and notably old transcripts of Sarkozy’s speeches. “Of course […], retrospectively it was stupid,” commented Sarkozy of the rental of the strongroom. The former president has been pitiless in court towards Guéant, his former right-hand man once nicknamed “the cardinal”.

The continuing efforts over Senussi arrest warrant

The trial also held surprises about the period post-2007. One of these concerned the alleged efforts by Sarkozy’s team to overturn the international arrest warrant issued against Abdullah al-Senussi. It had been established that Sarkozy’s close friend and lawyer, Thierry Herzog, travelled Libya at the end of 2005 to discuss the subject. But documents found in Takieddine’s computer hard disc suggested the efforts to withdraw the arrest warrant had continued after the 2007 election.

The documents mentioned a meeting between the Franco-Lebanese intermediary and Guéant, held on May 16th 2009 at the Élysée Palace, two years after Sarkozy’s election, when Guéant was the Élysée secretary general. The date of the meeting was recorded in the archives of the presidential office. In the document found on his computer, Takieddine noted the object of his discussion with Guéant was “to put aside” the warrant for Senussi’s arrest.

On January 15th, Guéant confirmed for the first time the subject of his May 16th 2009 meeting with Takieddine. He told the court that it was about the “closure of the Senussi case”, although the sense of the word “closure” was unclear. But what it did make clear was that between 2005 and 2009, the subject of the arrest warrant against state terrorist Senussi was very closely followed by Sarkozy’s team. It also established that in 2009 Guéant continued to have confidence in Takieddine despite what he claimed was a “trap” mounted by the intermediary in Tripoli four years earlier.

Enlargement : Illustration 4

The trial has also revealed how Takieddine was involved in the negotiations to free five Bulgarian nurses and a Palestinian doctor sentenced to death in Libya for supposedly infecting children with the HIV virus (Sarkozy sent his then wife, Cecilia Sarkozy, to accompany the medics out of Libya in July 2007), and that Takieddine was also involved in the organisation of the lavish welcome given to Gaddafi during his five-day visit to France in December 2007.

Nuclear cooperation with Tripoli

Sarkozy told the court that it was not himself but his superior, then president Jacques Chirac, who first opened up the possibility of a nuclear cooperation deal between France and Libya. During Gaddafi’s visit to France in December 2007 a number of economic deals, notably the sale to Libya of Airbus planes, were concluded, and a memorandum for the sale to Libya of a nuclear reactor was recorded. Sarkozy told the court that the memorandum had no great significance and was never followed up. “It’s diplomacy, it makes it possible to give content to visits,” said the former French president, minimising the issue.

But the problem with that version is that Anne Lauvergeon, the former boss of France’s nuclear power engineering company Areva, told the court on January 30th that the reason no nuclear deal was concluded with Tripoli was that she and her colleagues opposed the sale of the reactor to a dictatorship. “There are things that one doesn’t do […], you can’t sell nuclear [activity] to a country that does not function in a rational manner,” she said.

Lauvergeon recounted that Guéant, at the end of a meeting in the spring of 2010, had insistently asked that Areva cooperate with the Gaddafi regime. Guéant confirmed her account and, in contradiction of Sarkozy’s version, said that “work” on the subject had been held at “regular intervals” but that the project was blocked because Areva “did not budge”.

Saving Bashir Saleh

The trial has also shed light on another major chapter in the affair. This was the safeguarding by France of Bashir Saleh, Gaddafi’s former chief of staff and keeper of the regime’s secrets, on two separate occasions. The first occurred in November 2011, after the fall of the regime, when Saleh was arrested and held by Libyan forces opposed to Gaddafi (and who Sarkozy had, however, supported). The second time was in May 2012, when Saleh, who had been living in Paris, was exfiltrated out of the country just days after Mediapart’s revelation on April 28th that year of a Libyan document authorising the Libyan funding of Sarkozy’s campaign. It was also just days before the second round of presidential elections, on May 6th, which would see Sarkozy lose his re-election bid.

The document published by Mediapart, dated December 2006, was signed by the then head of Libya's foreign intelligence agency, Moussa Koussa. Saleh, then president of the Libyan African Portfolio (LAP), one of the main investment arms of the regime, was to be in charge of supervising the payments.

After having told the judicial investigation that he had “never” been involved in the first exfiltration of Saleh, Sarkozy finally admitted to the court on February 5th that he “gave a political agreement” to the operation, but that he was not aware of what happened afterwards, and notably the involvement of business intermediary and co-defendant Alexandre Djouhri, who organised a private jet with which Gaddafi’s right-hand man fled to France.

Concerning the second exfiltration, which occurred on May 3rd 2012, under the supervision of Bernard Squarcini, the director of France’s domestic intelligence service, and Djouhri, Sarkozy insisted he had no knowledge of the events. Yet France had been protecting Saleh, once the official closest to Gaddafi, despite a “Red Notice” issued by Interpol for his arrest.

“The Interpol notice was not a [matter of] priority,” Sarkozy told the court, adding that what he was concerned with at that time was a meeting he was to hold in Paris for his 2012 re-election campaign. “I have [sic] 120,000 people who are going to come to the Trocadéro [square], with my preoccupations, ‘Will it rain?’,” he said.

Amongst the mass of evidence collected over the ten-year judicial investigation is a report from the domestic intelligence service, the Direction centrale du renseignement intérieur, or DCRI (now renamed the Direction générale de la sécurité intérieure, or DGSI), dated September 19th 2011. The document, which the prosecutors presented to the court, detailed that Bashir Saleh’s personal lawyer had told French special services that during the war and NATO-led air strikes, it was his client who had “blocked” Gaddafi’s inner circle from circulating compromising evidence of the Libyan funding of Sarkozy’s election campaign.

Sarkozy has claimed that he was first introduced to Saleh well after his 2007 election. However, a video, which figures in Mediapart’s documentary film on the Gaddafi-Sarkozy funding affair, Personne n’y comprend rien (“Nobody understands a thing), shows Sarkozy and Saleh warmly embracing on the tarmac of Tripoli airport in July 2007, when Sarkozy visited Libya following the freeing of the five Bulgarian nurses and Palestinian doctor.

The video was shown in court on February 13th. It demonstrated that they already knew each other, and also that Saleh was the only Libyan who Sarkozy embraced among the group of officials present to welcome the French president. Claire Josserand-Schmidt, lawyer for the anti-corruption NGO Anticor, a civil party to the case, suggested to Sarkozy that the scene appeared more like the embrace of two men meeting up again than that of an introduction.

The former president first said he had “no recollection” of the scene. He then suggested that “it was just a gesture of recognition for his action in freeing the nurses”. When the subject of the video returned in a hearing on February 19th, Sarkozy declared: “The images show the opposite of what they are wanted to demonstrate. This video does not show any proximity.” He appeared as convinced as ever that it is words that shape reality, and not the contrary.

-------------------------

- The original French version of this report can be found here.

English version by Graham Tearse