Trumpism cannot be washed away with lukewarm water. That is the main lesson from the American presidential election. Yes, Joe Biden was elected as the 46th United States president. But this knife-edge victory, at the end of an election notable for the highest turnout since 1900, was also accompanied by numerous defeats for the Democratic Party in other contests.

Not only did the “blue wave” that the Democrats hoped for not materialise, they also managed to lose a number of seats in the House of Representatives. Nor have they managed to seize control of the Senate. On top of that there were many poor performances in local elections that took place on November 3rd, with the party failing to take control in several state legislatures.

Enlargement : Illustration 1

“We did not win every battle, but we won the war,” House speaker Nancy Pelosi told colleagues in an animated conference call with fellow Democrat House members on Thursday November 5th. But she did not specify for how long. For this war is certain to continue, given how strongly Trumpism has taken hold.

Donald Trump won close to seven million more votes than he did in 2016. He increased his vote share in all sections of society with the exception of white men. “More white women voted for Trump in 2020 than in 2016 despite his, to say the least, sexism,” said historian Sylvie Laurent on Mediapart's live discussion programme 'À l’air libre' on Thursday. This was also true of African-American and Latino women.

Enlargement : Illustration 2

Finally, Donald Trump did brilliantly with his own party's supporters. He has dispproved those Democrat leaders who were convinced that a section of the Republican Party electorate would shun such an unappealing character. It was for precisely this reason, to attract such voters, that they felt it vital to run a resolutely centrist and low-key campaign, in which they said as little as possible.

Joe Biden played on one thing and one thing only: that he was not Trump. He was “decent” and “professional”; he promised to “rebuild” a “broken America”; he committed himself to “restoring the soul of America”. His manifesto could be summed up in one simple proposition: a return to normal.

This strategy did what was necessary by winning him – just – the White House. But it was not sufficient. Not having control of Congress, and clearly not the Supreme Court, nor many state authorities, already Biden appears paralysed. He will just be a transition president, unable to pursue an agenda of transformation, as was the case with Barack Obama during his second term of office from 2012 to 2016.

The exit polls carried out on November 3rd, which are more reliable than other polls, and the initial analysis of the vote raise numerous questions about the weaknesses and failures of the Democrat strategy. The debate on these has already started in the party's ranks.

Many of these issues obviously find an echo in Europe and in France in particular. That is because there will be a presidential election here, too, in under 18 months. And because a powerful far right has been on the political scene for a long time, one that is already well-placed to go through to the crucial second round of the presidential election, as Marine Le Pen did in 2017.

Leaving aside the many peculiarities of the American system, four questions relevant to both sides of the Atlantic arise. There is, though, one key difference in relation to France; here the political landscape is split into many different groups, whereas the American voter just has a choice between two main parties.

- 1. The economy and the massive growth in inequality

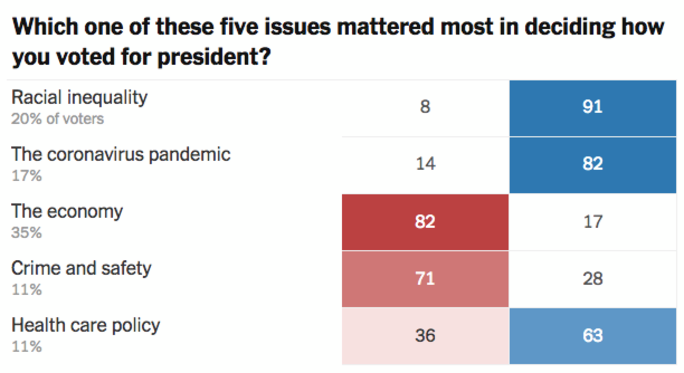

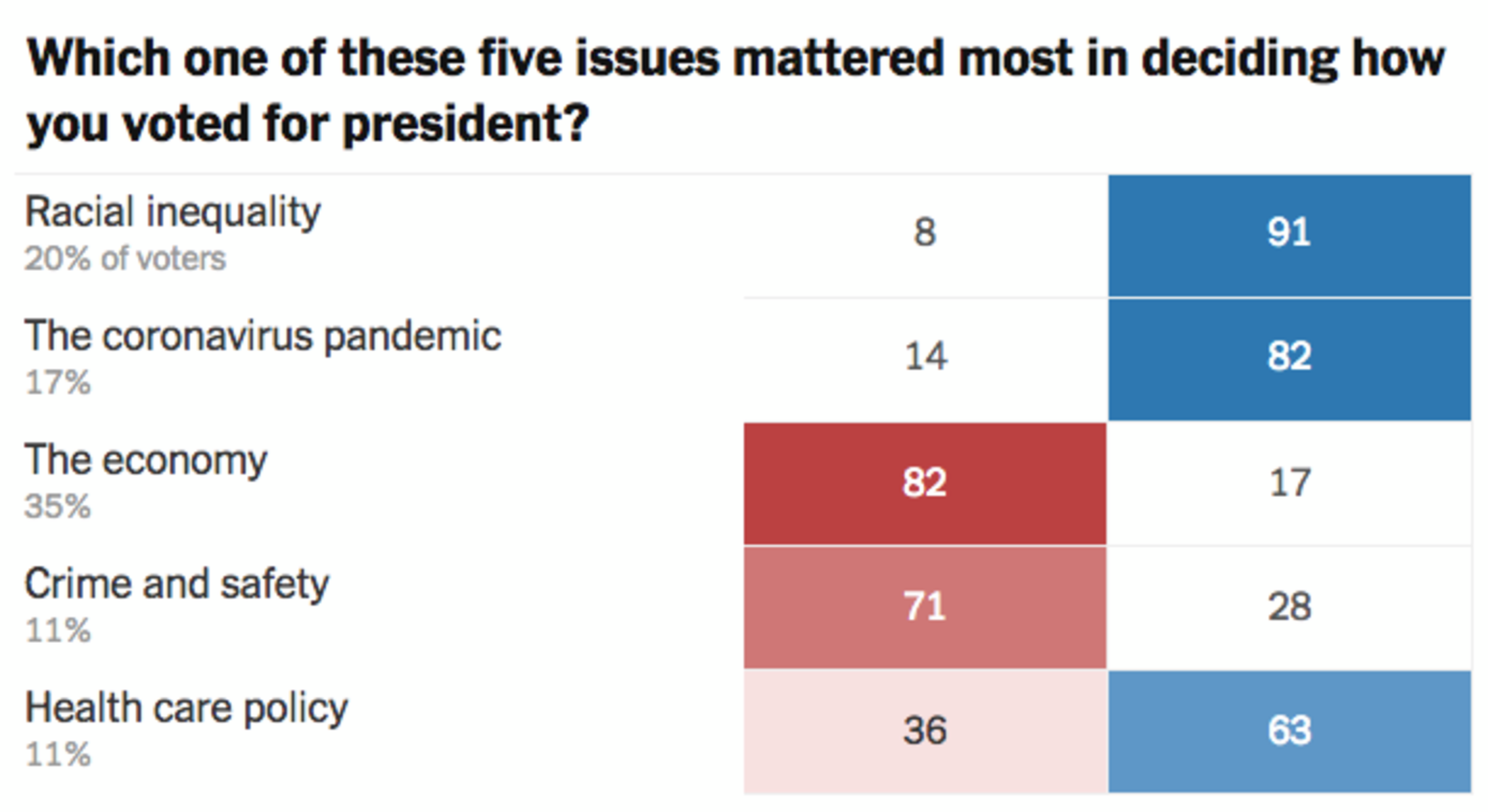

The economic situation was the single biggest factor for American voters (35%, against 11% for law and order and 20% for racism). Yet of those who placed the economy as the main motivation for their vote, 82% opted for Trump, against 17% for Biden.

Enlargement : Illustration 3

Paradoxically, the social and economic impact of the Coronavirus pandemic, which has seen 20 million more people left jobless, initially helped the incumbent, who constantly denied the seriousness of the “Chinese virus”. Trump was also credited with good economic results before the health crisis, results that were often due to his predecessor.

So while the United States has been torn apart by inequalities, and while Trump's policy was essentially to massively cut taxes for companies and the wealthiest, it was he who won on this major issue. The Democrats largely neglected social and economic issues.

It is true that Biden's team made some commitments on taxing the wealthiest. But this did not herald a major plan to kick-start the economy, redistribute wealth or fight against inequality. At the same time Biden constantly hesitated over the issue of shale oil and gas production, unsure of how to respond when Trump highlighted a sector which has produced jobs.

An illustration of this political impasse was seen in Florida. Trump ultimately won this state quite easily. Yet at the same time voters there backed an increase in the minimum wage to 15 dollars an hour in a local referendum.

In fact, the Democrats abandoned the domain of social and economic issues to the Republican candidate. This provides a useful lesson for politicians on the Left in France, where Emmanuel Macron wants to set a political agenda on national identity and security by using the language of the far right. And also where since 2017 Marine Le Pen's far-right Rassemblement National (RN) – successor to the Front National (FN) – has portrayed itself as a protector of the French people's economic interests. The socio-economic question is decisive, particularly during and after the health crisis we are currently witnessing.

2. A democratic and institutional crisis

In 2016 Trump was elected as the anti-system candidate (an old slogan of the FN/RN) who was going to get to grips with Washington, its lobbyists and the “deep state”, and drain the swamp. His ceaseless accusations of “plots” of all kinds, his refusal to accept the results of the election and his claims of “massive fraud” come against the backdrop of a clapped-out political system which, as in France, which has been made worse by a crisis in representative democracy itself.

Trump used his 88.4 million followers on Twitter – which is more than the 70 million votes he received on November 3rd – to speak directly to America, with no filters. As Paris-based American freelance journalist Harrison Stetler has written on Mediapart, the roots of the crisis that has been sweeping across the United States for thirty years go well beyond partisan politics. He argues that the violence that has spilled onto American streets is also the sign of a political or even a constitutional system that has failed to channel and give voice to popular opinion.

It is the same in France. Well before the 'gilets jaunes' or 'yellow vest' movement of late 2018 and its demand, among other things, for citizens initiative referendums, it was the very nature of France's Fifth Republic and its “presidential cretinism” that had put our democracy in crisis.

Let us cite just three examples. The right for foreigners to vote in local elections in France? That has been debated here for nearly 40 years and no progress has been made apart from for European Union citizens. The introduction of some form of even limited proportional representation for Parliamentary elections? It is a recurring promise that has never been kept. Thirdly, there is the Citizens' Convention on Climate, involving the direct participation of citizens in drawing up policy, which was set up by President Macron after the 'yellow vest' protests. No sooner was it done then it was promptly forgotten by the government.

Yet the issue of democracy is now centre stage. It is indeed the Fifth Republic that has to be removed, in order to build democratic debate. No party in France has chosen to make this a priority, with the exception of the radical-left La France Insoumise ('Unbowed France') who have proposed the creation of a “constituent assembly”.

- 3. Minority rights and emancipation for all

This issue is at the heart of the battle inside the Democratic Party. The “liberals” - broadly those on the Bernie Sanders left – are said to have scared off the traditional Democrat electorate in their fight for minorities. The movements for civil rights, against police repression, against white supremacists, against racism, the defence of illegal immigrants, support for LGBT rights and for Black Lives Matter and many other issues are said to have set a radical left, even a “socialist” political agenda, that supposedly paralysed Joe Biden and handicapped his campaign.

There is a striking parallel with France at a time when Emmanuel Macron wants to make the “fight against separatism” the theme of the rest of his term of office. This hysterical attack on the new enemy within, “communitarianism” - the forming of separate communities within a society, akin to multiculturalism – has been picked up by some on the Left. It is exactly the agenda which the far right wants to impose on the country, one of all-out warfare.

To prevent this backsliding towards xenophobic and identity politics, any plan to liberate people has to start with a defence of minorities and the establishment of new rights. The history of the Left in France, and its successes, have been punctuated with such commitments – and it is the same in the United States.

Enlargement : Illustration 4

As this debate begins in the Democratic Party it is worth noting that the four members of Congress from the left of the party were comfortably re-elected. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez (read her Twitter feed here), Ilhan Omar, Ayanna Pressley and Rachida Tlaib have reinforced the view that it is precisely these battles against racism and for new rights, and also for the Green New Deal, which have attracted new voters and mobilised new people.

The victory of Cori Bush (see our interview with her here, in French), the first black woman from Missouri to be elected to the House of Representatives, further strengthens their position. Without these new political struggles led by a new generation of activists, it is unlikely that Joe Biden would have been able to win in certain states.

- 4. Citizens movements and action on the ground

Indeed, this new American Left has known for some years how to develop new forms of action and forge unprecedented links with associations and the many local citizens groups based around the country. Following on from campaigns by Bernie Sanders, the “community organisers” have canvassed hard on the ground. They have campaigned, sometimes district by district, on very concrete issues such as poverty, violence, discrimination, health and the environment, which has helped re-engage people with politics.

“People need to really look at the communities who delivered these miraculous victories in Arizona, Georgia, Minnesota, Michigan etc. They are rarely a focus of traditional political investment or electoral strategy, & are often sacrificed in policy negotiations,” Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez noted in a Tweet explaining how local battles had helped assure a Biden win.

People need to really look at the communities who delivered these miraculous victories in AZ, GA, MI, MN, etc. They are rarely a focus of traditional political investment or electoral strategy,& are often sacrificed in policy negotiations.

— Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez (@AOC) November 6, 2020

One “thank you” would be changing that.

Here again French parties have a lot to learn. The meagre staffing levels of the left-wing parties or the green EELV party, and their remoteness from, suspicion of or lack of interest in everyday social struggles are a major handicap.

“Joe Biden and the Democrats have steadfastly refused to articulate a compelling alternative political vision to Donald Trump’s reactionary right-wing politics. Trump looks likely to have lost, but without creating an alternative to defeat it, Trumpism could return with a vengeance four years from now,” wrote Barry Eidlin in the left-leaning periodical Jacobin two days after the election (see also the article by philosopher Ben Burgis for Jacobin which Mediapart also translated into French).

The challenge is the same in France, faced with Marine Le Pen's Rassemblement National. One of putting forward a political project that is not about exclusion and identity; and building a global project that finally includes citizens and social movements. Is it too late? Without doubt.

Over the past three years there have been endless social protests and popular movements in France. Yet they have been looked on from afar or with suspicion by most of the so-called progressive, green or left-wing political groupings. These political groups have not known how to build on these sometimes unexpected and very often new movements which have sprung from society.

The old strategies, the insurmountable divisions, the blinkered ideologues, the battles of egos, with each person being convinced they are the person of destiny, make it impossible to build such a project. At the end of this road is the far right. Even though he lost, Donald Trump has just confirmed that. Unless...?

----------------------------------------------------------------------

- The French version of this op-ed can be found here.

English version by Michael Streeter