Following the official end of the bloody seven-year Algerian War of Independence in 1962, concluded by the Évian peace accords in March that year after 132 years of French colonial rule , tens of thousands of Harkis, the name given to Algerian auxiliaries who fought to alongside France’s army, were massacred in the North African country, along with their families, who were denounced as traitors to the independence cause.

They were largely abandoned to their fate by the French government – historians argue that between 30,000 and 150,000 of the Harkis and their dependants were murdered following the defeat of French colonial power – while Paris organised the repatriation of Algerian-born settlers of French nationality, known as the pieds-noirs. It is estimated that around 20,000 Harkis and their families were eventually allowed to escape to France, despite the reluctance of then French president Charles de Gaulle and thanks in part to the loyalty of French army officers.

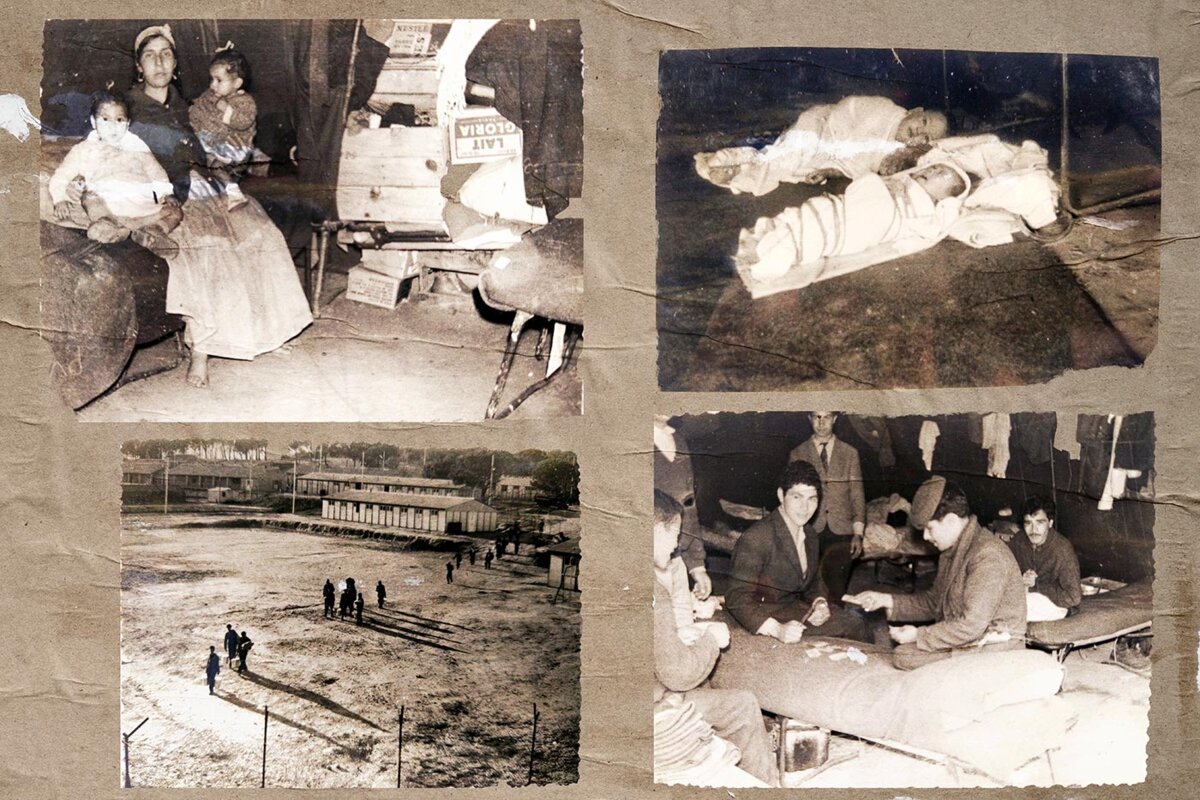

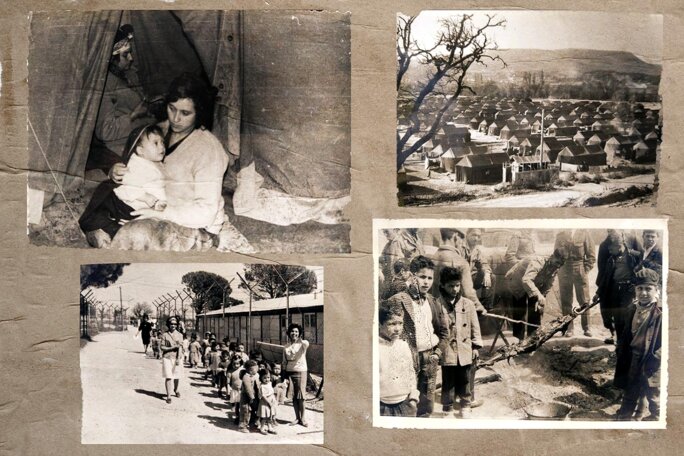

The unwanted former allies in what was a particularly vicious war, and who were often recruited in poor rural areas in Algeria, were mostly placed in so-called “temporary” internment camps, as tolerated by Paris and situated in isolated French rural regions, where conditions were often dire.

One of these was the camp of Saint-Maurice-l’Ardoise, located close to the village of Saint-Laurent-des-Arbres in the Gard département (county) in south-east France. Around 1,200 Harkis and their families were kept in the camp, many in tents, under army surveillance and surrounded by barbed-wire fencing. The winter that followed their arrival in 1962 was to prove extremely harsh, and especially so for the young children. Between November 1962 and March 1963, temperatures were recorded to have descended to as low as minus 15°C, and amid the deplorable living conditions came an outbreak of measles, causing the deaths of many infants.

Inhumation records at the camp reveal that 71 of the internees, including 61 children, were buried between 1962 and 1964. Included in that number were 31 infants who were buried in shallow graves at a makeshift site on military ground close to the camp. The camp was closed in the mid-1970s, and the location of the graves of the infants became surrounded in mystery. Many descendants of the Harkis were aware of the existence of the graves, notably among those children who survived their passage at the camp, now in their 50s and 60s, some of whom lost brothers and sisters. But precisely where they were hurriedly buried was unkown until 2019.

That was when a gendarmerie document, until then classified, was discovered in the regional archives. Among the revelations it contained was a diagram showing the area where the graves were found. But as has been the case throughout, the Harki families faced further frustrations in their search for the truth. Official excavations were finally carried out in February and March 2022 by France’s National Institute for Preventive Archaeological Research, but found nothing. A second dig in March this year at a parcel of land a little further north finally led to the discovery of 27 of the 31 graves.

The following month, on April 21st, the armed forces ministry’s junior minister for military veterans, Patricia Mirallès, visited the site where a wreath-laying ceremony was held in the presence of families of the Harkis, local politicians, and the media. At one point she held the hand of Aïda Seifoune, a woman in her eighties whose infant son Raoul was buried there – “like a dog”, she said.

Mirallès announced the future construction of tombstones and a dignified cemetery site. She also announced genetic testing for those families hoping to retrieve the remains of their relatives. “It is, in a way, giving life back to them,” she told journalists present. “We must also repair and recognise the harm that was done to them.”

According to Rachid Bedjghit, whose brother died in the dreadful conditions in 1962, Mirallès, meeting privately with a small group of Harki families and politicians before the ceremony began, said she had only recently discovered the story of the cemetery. “She said that it was ‘inadmissible’ but that she was ‘discovering’ all of this,” Bedjghit said. “I reminded her that she had the documents and written correspondence since more than a year.”

Enlargement : Illustration 1

The junior minister’s comments did not go down well. The French state had for long ignored campaigning for the identification of the site by activists among the Harki community, like Hacène Arfi, president of the “Coordination harka”, who has spent more than 20 years searching for the burial places amid general indifference. The authorities only finally took interest when they were confronted with the shocking gendarmerie report found in the regional archives. Written up in 1979, it described a proposal by the mayors of two municipalities bordering the burial site to move the remains to communal graves in local cemeteries, and this “without divulging” the move, and notably without informing the families.

The gendarmerie document was discovered in 2019 by Nadia Ghouafria, the daughter of a Harki fighter. She had spent many years scouring local archives for details of the makeshift graves. As part of her campaign, she created an association called Soraya, the name of an Algerian infant girl, born in 1961, who died in the Harki camp of Saint-Maurice-l’Ardoise in February 1963.

Enlargement : Illustration 2

The gendarmerie document, which Ghouafria succeeded in having de-classified, included not only a diagram indicating the rough position of the makeshift cemetery, but also a “provisional inhumation register” which revealed the extent of the tragedy. “Why had the discovery of a document in the archives been waited for in order to begin the first excavations?” asked historian Fatima Besnaci-Iancou, who is president of the scientific council of the memorial and cultural centre for the Saint-Maurice-l’Ardoise camp. “The children of the Harkis had lived through the events, they had already spoken of them,” she added. “But as long as there was no direct proof, no move was made.”

Almost four months have now passed since the team from France’s National Institute for Preventive Archaeological Research first revealed the locations of the children’s remains on March 20th. The cleared ground still has the appearance of wasteland, dotted with mounds of earth and surrounded by bramble bushes. Only the cuddly toys and flowers deposited here and there by families draw attention.

Among the families angered by the lack of consideration shown by the authorities is teacher Daniel Douaouia, who wrote to junior minister Patricia Mirallès on May 5th. “I only learnt yesterday, through an association, that my sister [lies] among the graves that have been found,” he wrote. “I regret that once again the state fails to live up to its responsibilities in writing to me directly. We are sickened, because on top of these indecent burial conditions, her grave was emptied.”

According to the gendarmerie document discovered by Nadia Ghouafria, nine other graves were exhumed in 1979, but it is unknown what became of those unearthed remains. “Who is behind that?” asked Douaouia, exasperated by the secrets that still surround the affair. “Where are the remains? We know of the will of the authorities at the time to transfer the remains to a communal grave site without informing the families. Is that the case?”

A few weeks after sending the letter, Douaouia received a phone call from the director of the local branch of the National Office for Military Veterans and War Victims, the ONACVG. “He said to me that he had my letter on his desk and he didn’t know what to say to me in answer,” Douaouia told Mediapart. “When I met him, he told me he could do nothing other than to take note of my complaints.”

“I asked the junior minister about this question of the exhumed graves when she came,” said Hacène Arfi. “She didn’t want to answer.”

The brother of Aïcha Djoubri, the daughter of a Harki soldier, and whose family now live in Normandy, was stillborn at the camp in December 1962. The name of her brother, Mohamed, does not figure on the burial records, but instead there is the mention “N° 4”. When their mother applied to receive her pension rights, she was unable to have Mohamed’s birth officially recorded, despite a specific request to the town hall of Saint-Laurent-des-Arbres, where the Harki camp was located. Mohamed’s very existence is denied administrative recognition.

“All of this adds contempt to the cascade of inadequacy,” commented Aïcha Djoubri. “Today, they must surely say that we’ve already waited 60 years and that we can wait for another 60. We’re going to lose ourselves again in the passage of time.”

Enlargement : Illustration 3

According to the Harki families, the local branch of the national office for war veterans has no plan for dealing with the complaints, nor any instructions about doing so. It appears that most of those who wrote to the junior minister have received no reply to their questions. An exception is a letter sent by Patricia Mirallès to the Djoubri family, dated June 19th, in which she announced that the construction work on the cemetery “should be finalised on September 25th 2024” (since 2003, every September 25th is a national day of homage to the Harkis).

The date for the opening of a transformed cemetery had not been made known to any of the Harki associations in the Gard département, and some voice doubts, based on past experiences, that it will even go to plan. According to sources close to the programme, no new excavations to find the still missing graves has yet been decided upon, nor has an investigation over the missing remains been planned.

While no agenda has been set for revealing the results of the DNA tests, there has been no official initiative either to trace relatives who have as yet not come forward. “To my knowledge, since 2019 no family has been contacted by the state,” said Nadia Ghouafria. “People ask themselves why they are discovering all that through the press.”

The office of the junior ministry for military veterans did not respond to Mediapart’s request for an interview, nor did it reply directly to questions submitted by email, instead referring to a statement issued on April 21st, the day that Mirallès visited the burial site. “I have the feeling that it will end up being the same story as what happened at the Rivesaltes camp, with a panel with names on it, and it will stop there,” said Rachid Bedjghit. “The only difference [there is] since the discovery of the site is the show of image,” he added, referring to the widespread media coverage of the visit by Mirallès.

Bedjghit is now planning to create an association in which to regroup all the families concerned by the burial site. To break the heavy silence weighing on them, many intend to now write to President Emmanuel Macron, and also the armed forces ministry, in yet another effort to avoid the story of the burial site from ending as it began, in contempt and shilly-shallying.

-------------------------

- The original French article on which this report is based can be found here.

English version, with added reporting, by Graham Tearse