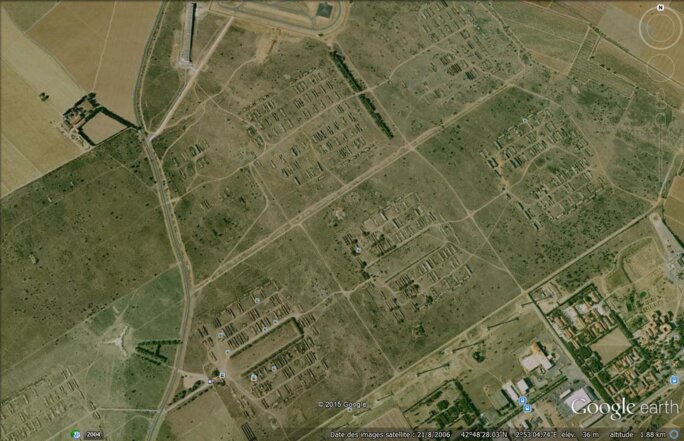

On the French side of the Catalan plain, to the east of the Pyrenees, a land baked by the sun in summer and buffeted for most of the year by the dry, northern Tramontane wind, stood an internment camp that represented many of the horrors of the 20th century, including those committed on French soil. Home to some 600,000 people from 1941 to 1964, Rivesaltes Camp held first Spaniards who had fled General Franco's regime at the end of the Spanish Civil War, then Jews and gypsies incarcerated by the Vichy regime, and finally Harkis who had fled Algeria after 1962, when the country won its independence from France, its former colonial master.

During the German occupation of France during World War II, about 2,300 Jews were deported from Rivesaltes to Nazi concentration camps, while hundreds of people died in the camp from malnutrition. Now, after 17 years in the making, a Memorial Centre dedicated to their suffering was inaugurated by Prime Minister Manuel Valls, whose parents were Spanish Republicans, on October 16th.

Enlargement : Illustration 1

In the aftermath of Franco's victory over the Republicans in February 1939, nearly 450,000 Spaniards crossed into France – a figure much cited since Syrians, Iraqis, Afghans and Eritreans fleeing war zones began to arrive in number in Europe. They were disarmed soldiers who had fought with Republicans, as well as civilians, and they were put in makeshift camps, many of which were on beaches near Rivesaltes, a village just north of Perpignan.

When France declared war on Germany in September 1939, the men among them were mostly allocated to Compagnies de travailleurs étrangers, units into which foreigners on French soil in wartime were grouped to do servicing work for the military. Women, children and the elderly often went back to Spain because of the sheer harshness of conditions in the camps.

"When France fell in spring 1940 there were about 170,000 Spanish refugees remaining in France," said Denis Peschanski, a historian at France’s national scientific research institute, the CNRS, who documented French internment camps in a thesis he presented in 2000 (and published by Gallimard as La France des camps. L'internement (1938-1946). Today, with the French population standing at almost 66 million in 2015, that number would be proportionally equivalent to 270,000 refugees, but France has offered to take in only a tenth of that figure in the current refugee crisis.

Peschanski, who chairs the scientific council for the Rivesaltes Memorial, explains that the camp was initially set up to receive Spanish refugees, and then from September 1939 housed Germans and Austrians who had sought refuge in France from Nazism, who were classed as citizens of enemy countries. After the French forces were defeated by the Nazis in 1940, the collaborationist Vichy regime, which managed the southern half of the country, sent Communists, Jews and gypsies to Rivesaltes.

"Between 1940 and 1942, administrative internment of 'undesirables' was an integral part of the Vichy regime but was marginal in the strategy of the occupying power, which favoured other repressive tools," Peschanski said. "After spring 1942 the internment camps became purveyors of convoys for deportation as part of the Final Solution."

Then, after the Liberation, the population of the camps changed. They became a repository for people suspected of collaborating with the Nazis or with involvement in the black market, amounting to some 60,000 individuals in the autumn of 1944.

Administrative internment was decided by the préfet, or local government official, without any legal recourse. It was, Peschanski said, "a phenomenon of exceptional scope in time and space, because it involved all the départements [equivalent to counties] and three regimes: the Third Republic, Vichy, and the emerging Fourth Republic."

Deadline after deadline was missed

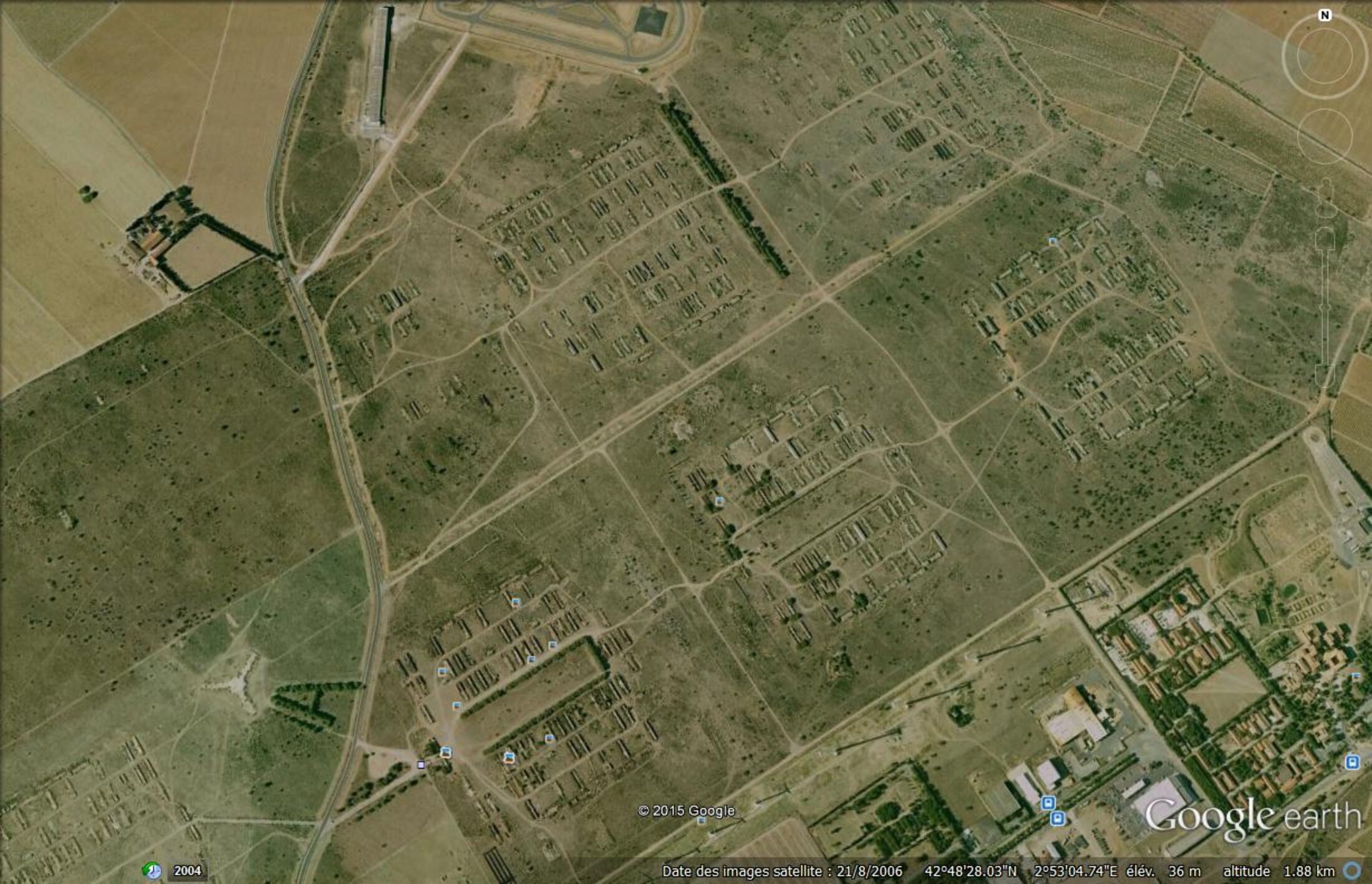

Rivesaltes was only one of around 200 French internment camps, but it was remarkable in two ways. Firstly, in terms of its size. It was a huge polygon four kilometres long and two kilometres wide, covering 612 hectares of rocky terrain a few kilometres north of the village itself.

Enlargement : Illustration 2

The army built the camp in 1938 and used it for soldiers who had been called up in September 1939. In late 1940 it was partially transferred to the Ministry of State for Home Affairs (secrétariat d'État à l'intérieur), as the army had been drastically reduced after the Armistice in June that year.

A month later, in December 1940, it became a centre d'hébergement, in the terms used at the time, a euphemism for a holding centre. Then in September 1942 it became the transit camp for the south of France, like Drancy in the north, a place where Jews rounded up by the Vichy regime were delivered to the Nazi extermination machine.

Secondly, in terms of its longevity. Once the southern zone had been occupied in 1942, the Wehrmacht set up its barracks at Rivesaltes. After the Liberation those barracks housed German prisoners of war, and later soldiers being sent to fight in Algeria transited through the camp before embarking at Port-Vendres just south of Perpignan. The same barracks were also used to intern militants belonging to the Algerian National Liberation Front (FLN), the main armed independence movement that fought against French colonial rule.

The great tragedies of the 20th century in France are present at Rivesaltes, and thanks to the Memorial, they can now be seen, and above all, felt. At Drancy, just north of Paris, you see the ironically named Cité de la Muette, built as a modern urban housing project in the 1930s, then used to detain thousands of Jews who had been rounded up and earmarked for deportation.

At Milles, close to the southern town of Aix-en-Provence, there is the former tile factory where first Germans and Austrians, then Jews, were confined. At Gurs, near Pau in the far south-west of France, seemingly endless rectilinear memorials have been erected and a forest planted. Nothing is left of the other camps, not even a commemorative plaque. But at Rivesaltes, the ruined barracks extend as far as the eye can see.

Enlargement : Illustration 3

The idea for a memorial emerged from opposition to the army’s plan in the late 1990s to raze the site. Local associations, with renowned Nazi hunter Serge Klarsfeld as a national figurehead, questioned that a place of such historical significance should be allowed to disappear. When the Socialist Party won control of Pyrenées-Orientales département in 1998, and Christian Bourquin became president of its general council, he said the first file he found on his desk was that of Rivesaltes.

Faced with the dilemma of what to do with the 600-hectare site – the army wanted to get rid of part of it – Bourquin contacted Peschanski, also a Socialist Party member, because he had come across Peschanski's thesis. The historian then became vice-president of the steering committee developing a project for the site.

Fast-forward to 2005, when the département acquired 42 hectares of the camp's former îlot F but was unable to finance the Memorial project by itself. Deadline after deadline was missed, and the conservative government, with an eye to re-taking Pyrénées-Orientales, was not about to help out. But when Bourquin in 2010 became president of the Languedoc-Roussillon region, in which the camp stands, the regional council took on the project.

And finally, the election of François Hollande as French president in 2012 ended the deadlock. For reasons explained further below, the project had been blocked at a national level despite having support locally from practically all political formations.

'The C20th was one of internment and forced displacement'

Work on the Memorial began in November 2012. The project was particularly dear to the heart of Kader Arif, then junior minister for veterans and a regional councillor, as he himself is the son of a Harki who was interned at Rivesaltes. But it got little encouragement from then culture minister Aurélie Filipetti. It received a boost when Ségolène Neuville, a socialist Member of Parliament for a constituency in the Pyrénées-Orientales, and who was also Bourquin's partner, became a member of the government, as junior minister for the disabled, in April 2014.

But it was not until Bourquin's funeral four months later – he had suffered from cancer for years – that the project got the governmental backing it needed in the form of a public promise of backing from Prime Minister Valls. Then the funding was complete: the département put up 7 million euros, the region 13 million euros, and the government 2.7 million euros.

Designed by Rudy Ricciotti, the architect behind the Museum of European and Mediterranean Civilisations, which opened in 2013 in Marseille, the Rivesaltes Memorial is evocative in its powerful understatement. Ricciotti says: "The Memorial is silent and oppressive: it rests in the earth and in the axis of îlot F with a calm, silent determination, a monolith of ochre concrete, untouchable, angled towards the sky. Both buried and emerging from the earth, the Memorial surfaces at ground level just after the entrance to the camp and extends to the eastern extremity of the former assembly point, up to a height equal to that of the roof ridge of the barracks."

Enlargement : Illustration 4

Enlargement : Illustration 5

The description is accurate. Even though the site sits between an industrial zone, a wind farm and a military terrain – the camp’s former îlot K is still owned by the intelligence services, the DGSE - the Memorial is a striking monument.

Inside, in the centre of a long hall, photographs and objects belonging to those who were interned are exhibited. All is in chronological order, with large, backlit panels summarising the main historical stages of life in the camp. Images constantly projected onto the wall show the misery of internees' existence. Cinema footage from the time shows the authorities' cynicism over internment policy. Tablets play internees' testimony. And in a separate space at the bottom of the hall, is a simple pronouncement: "The 20th century was the century of internment and forced displacement of people."

A fragmented legacy of remembrance

The Memorial also pays tribute to all those who helped, legally and illegally, to get internees out of Rivesaltes. “Eighty-seven children were deported from Rivesaltes between 1941 and 1942, which is obviously dramatic, but very few in proportion to the number of children who were interned there, and in comparison with other camps,” said Denis Peschanski. “Rivesaltes is also an exceptional site with regard to the amplitude of rescue operations that were put in place there.”

- Above: a series of photos depicting the camp between 1941-1942, with commentary, in French, by historian Thomas Fontaine, co-author of the texts of the Rivesaltes Memorial’s permanent exhibition.

Organisations that would today be described as humanitarian NGOs - such as the Quakers, the Young Men’s Christian Association (YMCA), Secours suisse, the CIMADE – were officially present in the camp and played an active part in rescuing people.

The circuit ends with a video interview with the representative in France of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, who underlines that the world today counts some 60 million refugees, compared with 40 million at the end of World War II, and that Europe has shown itself to be quite timid over welcoming just a small number.

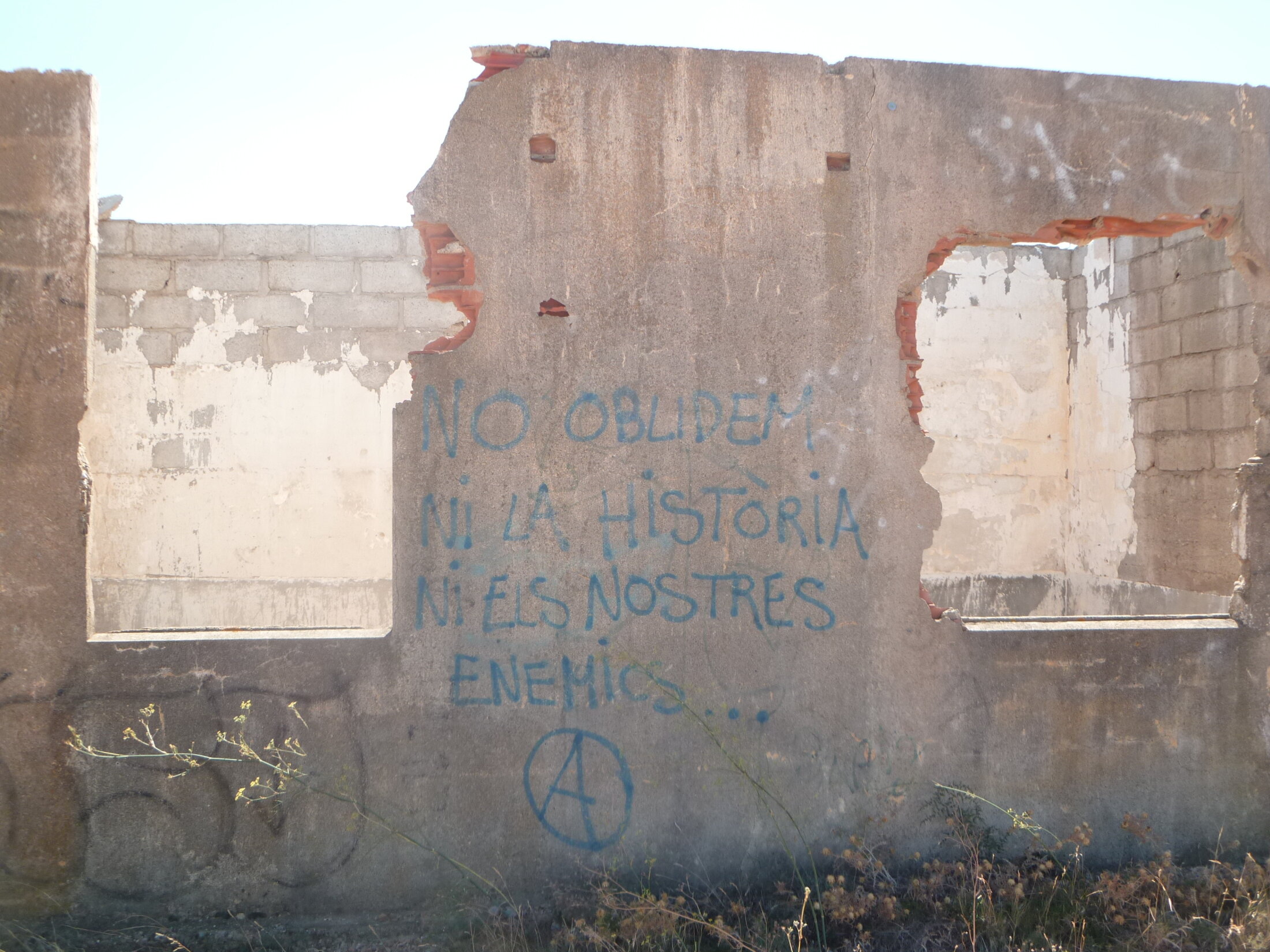

The permanent exhibition, set in a small sector of the camp's ruins, above all managed the feat of avoiding any opposition between the different populations which were successively interned in the camp decade after decade. For, on a small country road which crosses through the former perimeter of the camp is a series, built up over several years, of five small commemorative monuments.

Enlargement : Illustration 7

Enlargement : Illustration 8

These are tributes to the Jews interned in the camp (which dates from 1994), to the Harkis (1994), to the Spanish (1999) and to the Roma (2009). The CIMADE, which was already present in the camp during World War II, was behind the fifth. “Here, from February 1985 until December 2007, was an administrative retention centre where thousands of women and men were interned, whose only fault was that they were foreigners considered to be in an irregular situation,” reads the plaque it holds, referring to the internment of immigrants without legal status for residing in France. It then quotes article 1 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights adopted by the United Nations’ General Assembly in 1948: “All human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights.”

The four other memorial stones were created by different associations, which between them share an already fragmented remembrance. The local harki associations are as numerous as those representing gypsies, the latter taking up the duty of remembrance for the Roma who were interned in Rivesaltes, most of whom were from the Alsace-Moselle region of north-east France. The divisions between communists and anarchists remain present among the Spanish.

“The Memorial, from the beginning, wanted to refuse competition between these [collective] remembrances,” said Peschanski. It was because of this that it was possible to gain unanimous local political support for the project, ranging from that of the Left, which is notably sensitive to the Spanish Republican cause, to the Right and far-right, traditionally supportive of the harki cause (far-right Front National party vice-president Louis Alliot, who narrowly failed in his bid in local elections earlier this year to gain control of Perpignan town council, owns a house close to Rivesaltes) in a region where the former French settlers of North Africa, the pieds-noirs, make up a powerful section of the electorate. One week before the 2012 presidential elections in France, Nicolas Sarkozy, in his bid to win a second term in office, travelled to the site to place a wreath in remembrance of the Harkis interned in the camp.

- Above: In an interview with Mediapart (in French) historian Fatima Besnaci-Lancou, a member of the Memorial’s scientific council, explains the history of the internment of the Harkis. Of Harki origin, she was herself interned with her family in Rivesaltes as well as other camps in France.

It was the local right-wing politicians who were responsible for moving the administrative retention centre from Rivesaltes, when Sarkozy was interior minister, such would have been the embarrassment of having the camp’s new Memorial centre standing just a few hundred metres from a centre in which illegal immigrants were locked up.

Attracting visitors will be the Memorial's new challenge

While the Memorial has fully succeeded in meeting the challenge of uniting the different parties representing the camp's former internees, the challenge now will be to attract the public. The memorial’s director, Agnès Sajaloli, explained that a priority has been made of attracting school visits because, she says, “the memorial must set down bearings, in a context where they are missing for the young”. She has strongly campaigned to obtain agreement from the local education authorities that six teachers - two from primary schools, two from lower-age secondary schools (collèges) and two others from higher-age secondary schools (lycées) – be seconded a half-day every week to organize the pedagogical visits and stays.

Enlargement : Illustration 10

The second target is among the visitors to the region, which attracts a yearly average of 15 million tourists, which she hopes to draw via partnerships with other sites, such as the Céret Art Museum, and cultural venues, such as the Perpignan photojournalism festival Visa sur l’image, and the Prades Pablo Casals music festival.

Sajaloli, who is a former stage director and ex-head of the Lille national dramatic centre for the young, hopes to attract a local public partly through the staging at the Memorial of artistic shows which are based on the themes of internment and refugees, and evening ‘carte blanche’ discussions. In the coming months, guest artists will include the accordionist Bastien Charlery, choreographer Julie Nioche, actor Damien Bouvet, stage director Pippo Delbono and visual artist Anne-Laure Boyer. Former footballer Eric Cantona, whose mother, of Spanish origin, was interned in Rivesaltes, and the writer and 2014 Goncourt literary prize winner Lydie Salvayre, whose parents were Spanish Republicans, are booked for the ‘carte blanche’ meetings.

-------------------------

- The French version of this article can be found here.

English version by Sue Landau and Graham Tearse