Former French president Nicolas Sarkozy on Monday finally announced he is to run in his party’s November primary elections to choose its candidate for next year’s presidential elections.

Sarkozy, 61, who lost his re-election bid in 2012 in face of the socialist candidate François Hollande, also announced that as a result he was standing down from his post as president of his conservative Les Républicains party (LR) - formerly the UMP.

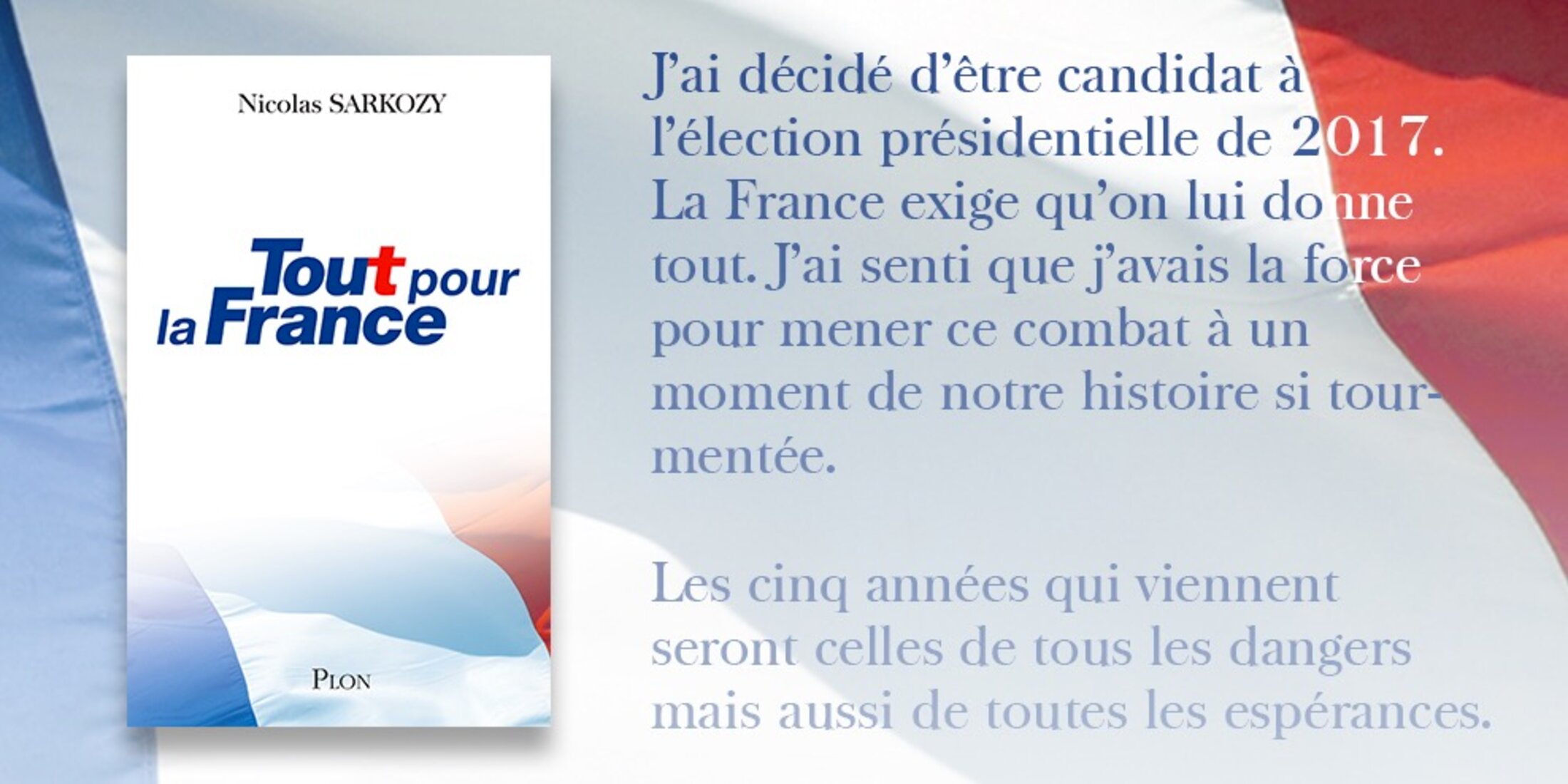

The announcement has been expected for months now, and Sarkozy dispensed with the usual method on such occasions of issuing a statement or appearing live on the main TV evening news, choosing instead to launch his campaign with the publication of a book setting out his political programme.

Tout pour la France (Everything for France) will be published on Wednesday but already extracts have begun circulating on the social media networks. The book is made up of five chapters, which together set the tone of what will be the former French president’s campaign for re-election: “The challenge of truth”, “The challenge of [national] identity”, “The challenge of competiveness”, “The challenge of authority” and “The challenge of freedom”.

On his Facebook account he declared that “This book is a departure point” of his campaign, which will open in earnest with his first public meeting on Thursday. Among the comments appearing on the account was one which asked: “Shouldn’t he be in prison?” For Sarkozy, who had initially hoped to automatically become his party’s candidate after taking over its leadership in November 2015, is heading into the race while implicated in a number of ongoing corruption investigations.

Enlargement : Illustration 1

The former president, who left his five-year (2007-2012) term of office under a cloud of scandals, is the only one of the now 11 candidates running in the conservative LR party’s primaries to also be formally placed under investigation in two judicial investigations. Other investigations in which he is implicated, although not as yet placed under investigation, are continuing, and some political observers have questioned whether Sarkozy’s judicial woes drove him to return as a presidential pretender despite his 2012 declaration, following his election defeat, that he was leaving politics. Under the French constitution, a serving president cannot be prosecuted for the offences he is suspected of.

Sarkozy is placed under investigation – a status in French law which is one step short being charged but which requires that there is strong or concordant evidence of having committed a criminal offence – in what has become known as the “Paul Bismuth affair”. More precisely, he is under investigation for suspected “corruption”, “influence peddling”, and “receiving” information obtained through “the violation of professional confidentiality”. The investigation centres on Sarkozy’s alleged corruption of a senior French magistrate, Gilbert Azibert, by offering to use his influence to obtain for the magistrate a prestigious post in Monaco in exchange for Azibert’s help in a case involving Sarkozy.

Sarkozy is suspected of seeking Azibert’s help to ensure that a number of the former president’s diaries, seized as evidence in the Liliane Bettencourt affair, were returned to him before they could be transferred to another investigation.

That other investigation concerns the awarding of more than 400 million euros of state funds to French tycoon Bernard Tapie in 2008, one year after Sarkozy was elected president.

Until Sarkozy’s election, Tapie, a flamboyant high-profile figure who had actively supported Sarkozy’s election campaign, was involved in a protracted court battle to obtain damages from the state for his alleged spoliation in 1993 by the now defunct state-owned bank Crédit Lyonnais. Soon after Sarkozy’s election, the dispute was transferred by the government into private arbitration, a move that resulted in the exorbitant award one year later.

The current International Monetary Fund chief, Christine Lagarde, who was at the time Sarkozy’s former economy and finance minister, has now been sent for trial for “negligence” over her role in the affair, which was key to allowing the arbitration process. It is suspected that she was obeying orders from Sarkozy. Meanwhile, the award to Tapie was annulled last year by the Paris appeals court.

Sarkozy’s plan to use Azibert to obtain his diaries before they could be transferred as evidence in the Tapie arbitration case was discovered during phone taps placed on a mobile phone given to him by his lawyer, Thierry Herzog. The latter had taken out the mobile subscription under a false name, that of Paul Bismuth. During the phone taps, Sarkozy and Herzog, were recorded discussing the plan.

Herzog and Sarkozy failed in their bid to have the case dropped on the grounds that the phone taps were illegal, and the investigation appears to be drawing to an end. That would likely result in Herzog and Azibert - who were also placed under investigation - and Sarkozy being sent for trial. But the French legal process is notoriously long, and if the three are sent for trial they then have a three-month period in which to challenge the conclusions of the investigating magistrates leading the case. Once that process is completed, the public prosecutor’s office must then give its recommendations, which means that it now appears certain Sarkozy cannot stand trial before the presidential elections due in May 2017.

If Sarkozy, who denies any wrongdoing, were to win his party’s primaries, and then go on to win the presidential elections, he would escape prosecution during his mandate.

The second case in which the former president is implicated involves the disguised overspending of his 2012 election campaign, for which he was in February placed under investigation for “illegal financing of an electoral campaign”.

Sarkozy’s campaign is suspected of having spent double the legally-imposed ceiling of 22.5 million euros by a system of false invoices. The gross overspending was hidden with the help of communications firm Bygmalion and its events subsidiary, which billed Sarkozy's right-wing conservative UMP party (now renamed Les Républicains) for various services that should have been charged directly to the election campaign. In what has become known as the Bygmalion Affair, no evidence has been found that clearly demonstrates that Sarkozy gave orders to disguise the overspending, nor even that he was informed of the system that was set up. His allies underline that he has not been placed under investigation for “fraud” or “abuse of confidence” in the affair, unlike others.

However, the magistrate leading the investigation, Judge Serge Tournaire, has indicated that Sarkozy could not have been unaware of the overspending, notably given warnings issued over the matter by party accountants and an email sent by the party’s director-general in March 2012, two months before the elections, which mentions “the president’s wish to hold a public meeting each day”, which represented a notable acceleration of the campaign.

Sarkozy denies having any knowledge of the breach of spending and the fraudulent invoicing system.

Examining magistrates decide who stands trial

If sent for trial over the campaign overspending, Sarkozy would face a maximum jail sentence of one year and a fine of 3,750 euros. The judicial investigation was wrapped up in June this year, and the public prosecutor’s office has until early September to present its own conclusions as to whether Sarkozy should be sent for trial. The lawyers representing Sarkozy and the 13 other people placed under investigation are also entitled to present their own “observations”, which can include challenging certain elements in the case or demanding further enquiries, all of which would delay the procedure further.

As in the corruption case in which Sarkozy is placed under investigation, it is the examining magistrates who led the investigations who have the final say as to who stands trial, whatever the recommendations of the public prosecutor’s office. It would be difficult to imagine that Judge Tournaire, who placed Sarkozy under investigation, would subsequently decide that Sarkozy should not stand trial, but what final decision will be taken by another judge who was previously involved in the investigation, Renaud Van Ruymbeke, is unclear.

In February, Van Ruymbeke made known informally that he disagreed with Toutrnaire’s decision to place Sarkozy under investigation. If Van Ruymbeke opposes the sending of sarkozy to trial on charges of illegal campaign financing then this would possibly delay things further, although Judge Tournaire would have the final word given that he is the magistrate who led the case at its end. A third magistrate who was also earlier involved in the investigation, Judge Roger Le Loire, will have no say after he was stood down following his announcement that he was considering launching himself on a political career. The result is that a decision to send Sarkozy for trial could be taken in 2017.

Sarkozy is implicated in other investigations, although for the moment he has escaped being placed under investigation in any of them.

One is the Karachi affair, which involves the use of cash from secret commission in French arms sales abroad to fund former French prime minister Édouard Balladur’s 1995 presidential election bid, for which Nicolas Sarkozy, Balladur’s budget minister, was spokesman. While six people, former senior political aides and businessmen, have been charged with this far-reaching scandal (see more here and here), the judicial investigation has advised that three then-government members implicated in the case should be the subject of a separate investigation by the Cour de Justice de la République (CJR), which is a special entity dedicated to investigating and eventually trying former ministers for misdeeds during their term of office. The three are Édouard Balladur, his defence minister François Léotard and Nicolas Sarkozy. The criminal investigation recommended to the CJR that Balladur and Léotard were susceptible to being placed under investigation, while Sarkozy was regarded as a potential “assisted witness” in the case, which is a less serious status but which implies there are grounded suspicions of his involvement in wrongdoing. That recommendation was made two years ago, and the CJR, notoriously slow and cautious in its procedures, appears unlikely to be ever placed under investigation by the court, a necessary step before he could be sent for trial.

Concerning the ongoing judicial investigation into the suspected financing of Sarkozy’s 2007 presidential election campaign by the regime of the late Libyan dictator Muammar Gaddafi, as first revealed by Mediapart (see here and here), the outcome remains uncertain despite the compelling evidence that the Gaddafi regime approved the funding.

Sarkozy’s retroactive presidential immunity could apply to two other cases in which his name is cited. One of these involves the sale of helicopters to Kazakhstan by France in 2010, in which two of Sarkozy’s aides have been placed under investigation on suspicion they took illicit kickbacks from the deal. It is alleged that the French officials put pressure on Belgium to ease legal proceedings against Kazakh oligarchs, as part of a condition for the trade deal. Former Senator and personal representative of Sarkozy’s, Aymeri de Montesquiou, and Jean-François Étienne des Rosaies, Sarkozy’s former diplomatic advisor, have been placed under investigation in the case.

The other case is the suspected misuse of public funds and favouritism in the commissioning of opinion polls by the French presidential office during Sarkozy’s 2007-2012 term of office. The polls, of questionable public interest, were assigned without any prior public tender to firms with close links to presidential advisors. Several former Sarkozy aides are now placed under investigation in the suspected scam.

While Sarkozy has often denounced a supposed partiality against him by examining magistrates, even attempting in vain to bring in legislation removing them from their current role as independent investigators, he has, unlike his predecessors, used the legal apparatus on several occasions while interior minister and, later, president, to bring proceedings against those who crossed his path.

This includes the prompting of investigations to find the thief who robbed one of his sons of his scooter, the hackers who broke into his bank account, and those responsible for spreading rumours about his private life. The most notable case was the Clearstream affair, in which Sarkozy used all his influence, in vain, to secure the conviction of his arch conservative rival Dominique de Villepin, the former French prime minister.

-------------------------

The French version of this article can be found here.

English version by Graham Tearse