Behind the huge sliding glass doors the slender outline of Idriss approaches and comes to a halt in an area that looks rather like a kitchen: there is a sideboard and tables laden with large plastic containers of drinking water, while an oven and fridge also equip this open-plan room. Everything is perfectly tidy, very different from the scenes of chaos that greeted the young man when he arrived one morning ten days earlier, during a parliamentary election campaign marked by the rise of the far-right in France.

“There,” he says, pointing with his finger, “the sideboard was overturned; they trashed everything and put washing-up liquid in the drinking water…” Photos of the mess caused show a machete stuck intimidatingly in the wooden worktop, with a second one buried into the sideboard. There were several graffiti tags, too, one declaring “Fuck Hamas” and another signed “FLB” for “Front de Libération de la Bretagne”, a Breton independence organisation. The attacks took place on the nights of July 1st and 2nd.

There is a sense of total disbelief among everyone involved in the project about these racist attacks. The A4 association, which supports migrants wanting to start careers in agriculture and crafts, opened a branch here at Lannion in Brittany in September 2022. Idriss, who's in his 30s, is pretty much in charge of the place: a Sudanese exile, who lacked official documentation for a long time but whose immigration status has now been regularised, he launched the project and is its only employee. It was he who in 2023 oversaw the erection of greenhouse on this plot of land, which was made available to the association by a private landowner.

Enlargement : Illustration 1

The team started with a simple range of produce, before expanding it in September 2023 with the help of the collective group 'Reprise de savoirs' to include tomatoes, melons, watermelons, squashes, aubergines and peppers. During the second incident, the attackers targeted the tomato plants.

“Some members were shocked, others angry. They didn’t understand what we'd done to deserve something like this,” says Clarisse, who used to work for the association, and who is now a volunteer, when Mediapart met the team on Thursday July 11th.

Racism exacerbated by the elections

“I'm afraid it will happen again and that one day they'll hurt someone,” adds Idriss, who has reported each of the two attacks to the authorities. The advice he was given by the police? It was to “install cameras” to help identify the perpetrators.

Idriss recalls how, on the evening of one of the attacks, he met an undocumented Cameroonian woman who lives in Lannion and who told him that she had come across two people on bicycles making monkey noises at her. He is not sure if this was a coincidence or if the two events were linked.

The market gardener is aware that he was the target of the attacks. Many in the area even call the place the “Idriss greenhouses” after him. He adds: “But ultimately, it targets all of us because there are foreigners in the group.” They are about twenty in total, explains Clarisse, with a core group of five active volunteers.

I've experienced a lot of violence in my life, but emotional violence is the toughest.

Bolivians, Chadians, Congolese, Colombians and Afghans mingle here, each with different statuses, including that of rejected asylum seekers, asylum applicants and undocumented immigrants, some of whom who are subject to an 'OQTF' or order to leave France. As with Emmaüs Roya, the organisation set up by olive grower Cédric Herrou in the Alpes-Maritimes département or county in south-east France, the greenhouses give migrants the chance to develop social ties while undergoing training.

The racist incidents should be seen in the context of the recent elections and the rise of the far-right in France, according to Clarisse and Idriss. However, Idriss notes that there had already been an increase in the number of racist acts or attacks in recent years. “Some people hate foreigners and now feel free to express it. I've experienced a lot of violence in my life, but emotional violence is the toughest,” he says.

Enlargement : Illustration 2

As he fiddles with and tears a piece of paper between his fingers, the Sudanese market gardener recounts the racist attacks he has personally endured in the region. One day while walking along the road he was stopped by a motorist who insulted him and shouted: “What are you doing here? You have invaded France!” Another time, during the lockdown, he was reported to the police by an elderly woman while distributing food supplies to isolated people in Lannion; she had been frightened at seeing a black man in front of her house.

He also recalls his initial arrival in the nearby commune of Trébeurden, after the dismantling of the Calais “jungle” or migrant camp in northern France in 2016. Nearly fifty asylum seekers had been transferred to a reception and orientation centre, before being accommodated in a reception centre for asylum seekers, known as a CADA. Well before the recent episodes in Callac or Saint-Brevin-les-Pins, their arrival had sparked demonstrations by far-right movements who opposed the idea of hosting migrants in Brittany.

A place where migrants move freely

When the plot of land was handed over in 2022, the landowner warned Idriss of the venomous reactions that the A4 project might provoke in the neighbourhood. “He told me there were racist people,” the market gardener recalls. But, as Clarisse notes, there are also “quite a few supporters, farmers who come to visit us and bring some of their products”. Examples are the neighbouring shared gardens, known as 'Chez Prosper', and some nearby farms.

Another local association, 'Étincelles', has welcomed them with open arms. On Friday, July 12th, the A4 team received a visit from Marion, one of the founders and managers of that body. For many years she had worked for the state-mandated organisation that welcomes and accommodates asylum seekers in the region, known as AMISEP.

“We had started French as a Foreign Language (FLE) classes, but AMISEP had to abruptly stop them due to financial reasons, and our contracts were not renewed,” she explains in the greenhouses as she helps Idriss pick ripe tomatoes. That was how the Étincelles association was born. Since then it has been offering socio-linguistic workshops to residents of the Lannion CADA and anyone else interested, including members of A4.

Enlargement : Illustration 3

“We come here once a week. And the idea is that people feel able to come back at other times without us,” says Marion. These include Olga, a Ukrainian woman who enjoys doing odd jobs here. Others come to water the plants or bake bread. “Our activities revolve around market gardening, bread-making, welcoming visitors, maintaining the premises, and organizing events,” explains Clarisse.

Whether they are seeking asylum or waiting for their status to be regularised, many of the people face a “long wait”, notes Marion, who sees this place as a “giant play area where there's always something to do”.

There was nothing political in the texts, except for the names that appeared there.

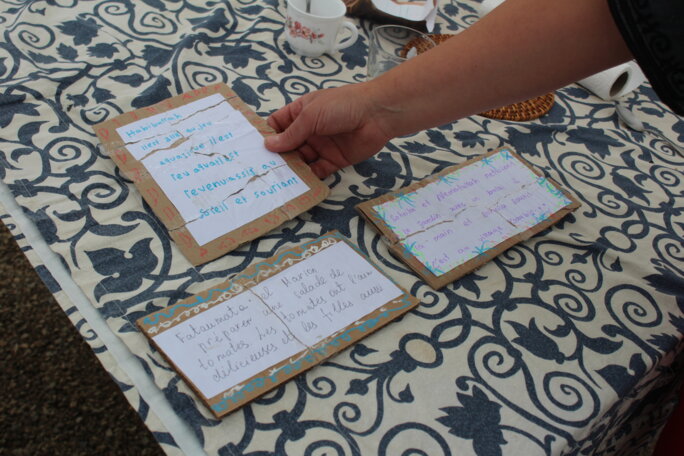

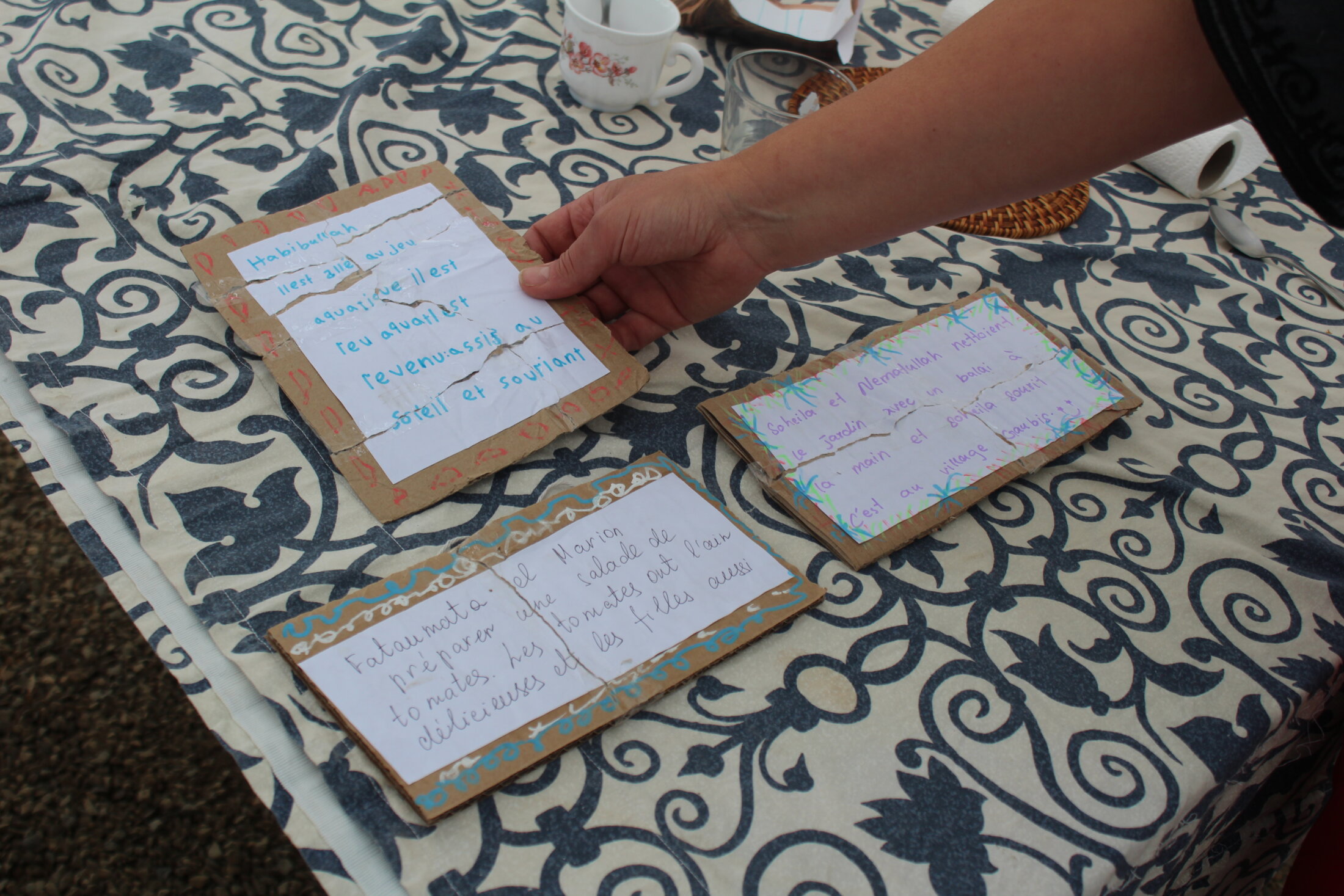

A few days before the attacks, members of Étincelles wrote short texts about photos taken during their workshops, with the aim of exhibiting them in the greenhouses. “They were hung up, and the people who vandalised everything ripped them up. There was nothing political in the texts, except for the names that appeared there”, says Marion, a reference to the fact that these names were of foreign origin.

On a table she lays out the pieces of paper she is going to stick back together, revealing the names that the attackers wanted to erase: Soheila, Fatoumata, Nematullah. The exhibition was taken down the day after the first attack, for fear that “they would do it again.” Marion says: “Our association was collateral damage. A4 was targeted because it's seen as a place of activism, and because there are foreign people there.”

For Éric Bothorel, the newly re-elected MP for Emmanuel Macron's centre-right Renaissance Party representing the local Côtes-d’Armor département, these acts of “vandalism” and the “macabre display” – a reference to the machetes stuck in the furniture - are simply “unacceptable”. Speaking at his office in Lannion he says: “Regardless of people's status, they need support; I don't differentiate between criminal acts.” He visited the site during the parliamentary election campaign, to show his support.

Active far-right networks in the region

Convinced that the perpetrators “did not choose their target at random”, the MP is less sure about the message they intended to convey. “The FLB hasn't been active in the region for a while. And the mention of Hamas is odd,” he says. Marion, from the Étincelles association, suggests a possible explanation: the greenhouses hosted a group of pro-Palestinian activists earlier in the year. “We're in Trégor [editor's note, one of Brittany's traditional provinces], so it’s very white. The presence of black people, veiled women, people wearing a keffiyeh, that can unsettle some,” she says.

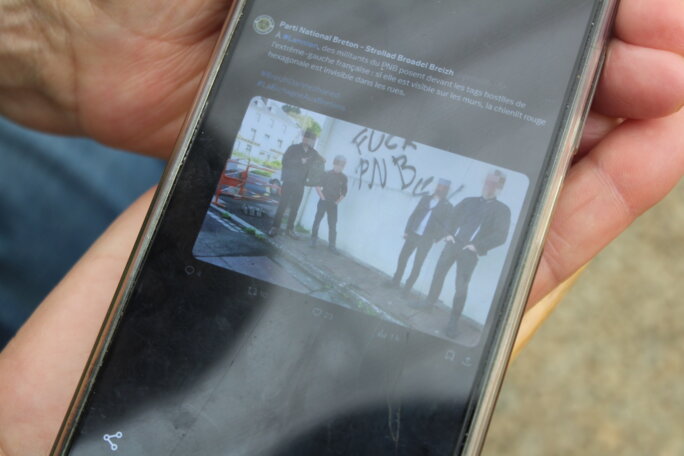

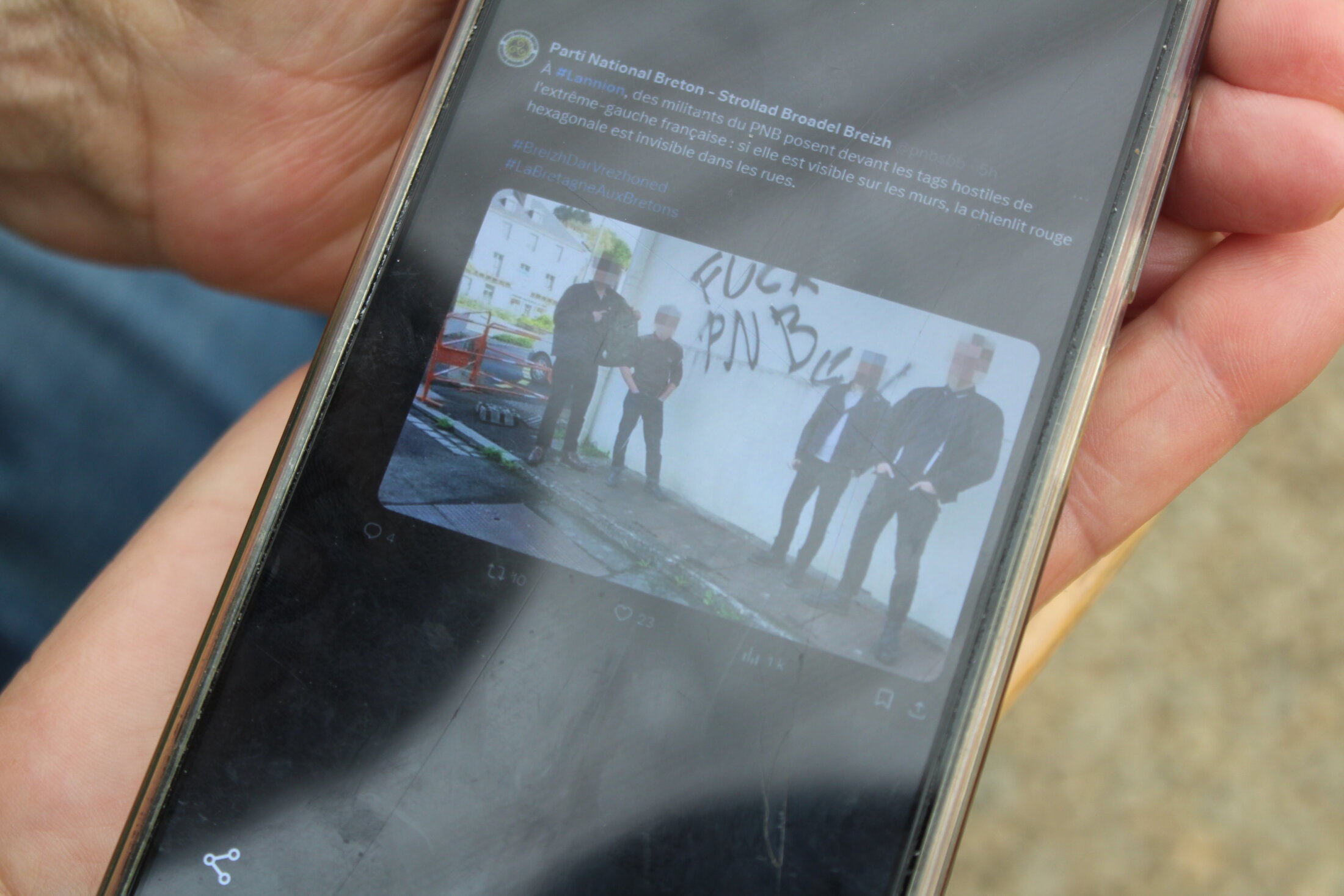

Others voice doubts that it was the FLB who were involved. “What we do know, however, is that there are militants claiming to be from the PNB, the Breton National Party, whose ideas are clearly far-right,” note two observers monitoring the progress of the far-right in Brittany.

Enlargement : Illustration 4

According to these observers, five individuals have been identified in Lannion. Several of them posed in front of an antifascist graffiti tag targeting the PNB to assert their closeness to the party, before posting the photo, with their faces blurred, on social media. The observers note a “significant and very worrying network” of the far-right in the region, including fundamentalist Catholics, descendants of Nazis, members of the now-banned GUD far-right student group and Breton nationalists.

“Some gravitate around several different movements. There are small elites with money and influence, and there are foot soldiers, capable of actions like the greenhouse attack,” say the observers. For this attack is not an isolated incident in the Côtes-d’Armor département: on November 17th 2023, a similar site in Saint-Brieuc was also targeted.

In that episode three masked men broke into the premises of 'La Serre' association and assaulted the occupants, leaving four people with minor injuries. The men were identified thanks to surveillance measures set up by the anti-fascist group, the Collectif de Vigilance Antifasciste (CVA22), the observers explain. The culprits were later given six-month suspended prison sentences.

By doing that, they put a target on their backs.

A member of the CGT trade union who followed the case says that at the court hearing the men had called for “Brittany for the Bretons”, a “white Brittany” and a fight against antifascists. “The [presiding judge] pointed out to them that they weren’t even originally from Brittany,” the official says.

During the parliamentary elections, far-right activists used social media to circulate photos of anti-racist activists who were demonstrating in support of Lannion being a “place of welcome”. “By doing that, they put a target on their backs,” note the observers, who were also alerted to anti-Semitic graffiti - with Stars of David - and Celtic crosses in the Ker-Uhel neighbourhood of Lannion, between the two rounds of the election held on June 30th and July 7th.

Enlargement : Illustration 5

The victims of Saint-Brieuc quickly contacted Idriss in early July to offer their help. Since then, a sign reading “You're being watched”, accompanied by the illustration of an eye to indicate that the area is under surveillance, has been put up a few metres from the plant beds in the greenhouses to deter potential attackers.

The mayor of Lannion, Paul Le Bihan, has not yet visited the site. Questioned by Mediapart, the elected official said he was “shocked” by these acts, which he learned about through the press. “Lannion is not used to this, so there's both surprise and the issue of who did this and why,” he said.

He talked about the associations and collectives in his area, including the Collectif de Soutien aux Sans-papiers – which helps undocumented migrants - which he said he “supports symbolically”. The mayor also said he was aware of the migrants' backgrounds, particularly that of Idriss, who has been involved with several local organisations for many years.

“The political context has been a breeding ground for such excesses, and it's not calmed down, even though the elections are over. The best response is to show solidarity with the victims of this racism,” Paul Le Bihan said. Meanwhile, Idriss and his comrades are hoping to find office premises for the association. They have been in discussions with the town about this for some time, so far without success.

“We need a space to meet and work in a warm environment during the winter, to seek internships and training for A4 members,” says Idriss, who remains aware of the difficulties of settling in the region as a farmer “when you're a foreigner”. He concludes: “It's not easy, but we're trying. No matter what happens, I'm staying here, and I'll carry on campaigning.”

----------------------------------------------------------------------------

- The original French version of this article can be found here.

English version by Michael Streeter