On Monday June 3rd 2019 two French citizens were sentenced to death by an anti-terrorist court in Baghdad for having joined Islamic State. That brought to twelve the number of former residents of France – eleven French citizens and one Tunisian – who have been given the death penalty in Iraq in the last nine days for their role as jihadists.

The men's varying backgrounds help paint a portrait of the French jihadists who joined the project to construct a Caliphate in the region between 2013 and 2014. They are men aged between 24 and 41, some of whom came from well-known recruiting grounds for jihadists in France such as the Paris region, Toulouse in the south-west and Roubaix in the north, but others who hailed from new recruiting territory for the radical Islamic propagandists such as Lunel, a small town in the south of France near Montpellier from where around 20 would-be jihadists set off for Syria.

Some had been on the radar of the anti-terrorist intelligence community in France, such as Leonard Lopez, the former manager of the French-language jihadist website Ansar al-Haqq, for which role he had been given a five-year jail term in France. But Mustapha Merzoughi, for example, a former soldier who had served in the French army and fought in Afghanistan, was not known to the authorities.

These men had carried out various roles within the Caliphate and experienced different fates. According to the Center for the Analysis of Terrorism (CAT) in Paris, a man called Mourad Delhomme became a judge on Islamic State courts and regularly ordered corporal punishment and summary executions. Another man, Yassine Sakkam, from Lille in northern France, who was wounded in fighting, saw his brother die in a suicide attack on the Iraqi-Jordanian border. After IS's defeat in Syria he stole a vehicle which he then gave to a people trafficker in order to get him out of the country. But it was not considered sufficient payment. Then after the convoy in which he was travelling halted, a second trafficker - who was supposed to lead them to the Turkish border - instead handed them over to the Kurd-dominated Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF).

Enlargement : Illustration 1

Two men in particular stand out among the twelve who have been condemned to death. Brahim Nejara appeared in an IS video entitled 'Paris has collapsed' which glorified the attacks in the French capital on November 13th 2015, and which was broadcast eleven days later. According to a statement by one of his brothers, Brahim Nejara had urged him to carry out a massacre in France by buying weapons and firing into a crowd. According to the French domestic intelligence service, the DGSI, the jihadist held a “high-profile position inside the terrorist organisation”.

Brahim Nejara was based at Shaddadi in the Syrian desert on the border with Iraq and worked for the Islamic State police, in all likelihood for its feared secret service the Amniyat. Here he carried out summary executions and trained jihadists in the 'free fighting' he had done in the Lyon region of eastern France. “Brahim sent me photos of the police station were he was working, photos on a tank, in an armoured car,” one of his brothers later said. “I also saw a photo and two videos in which he was armed, he was firing an enormous sub-machine gun on a tripod with a big box containing cartridge clips....One day he sent me a photo in which he was having a go at two guys sitting on the ground. The prisoners weren't tied up but they had hoods.”

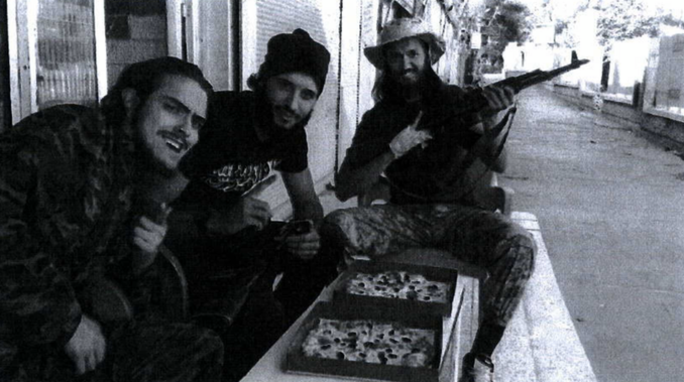

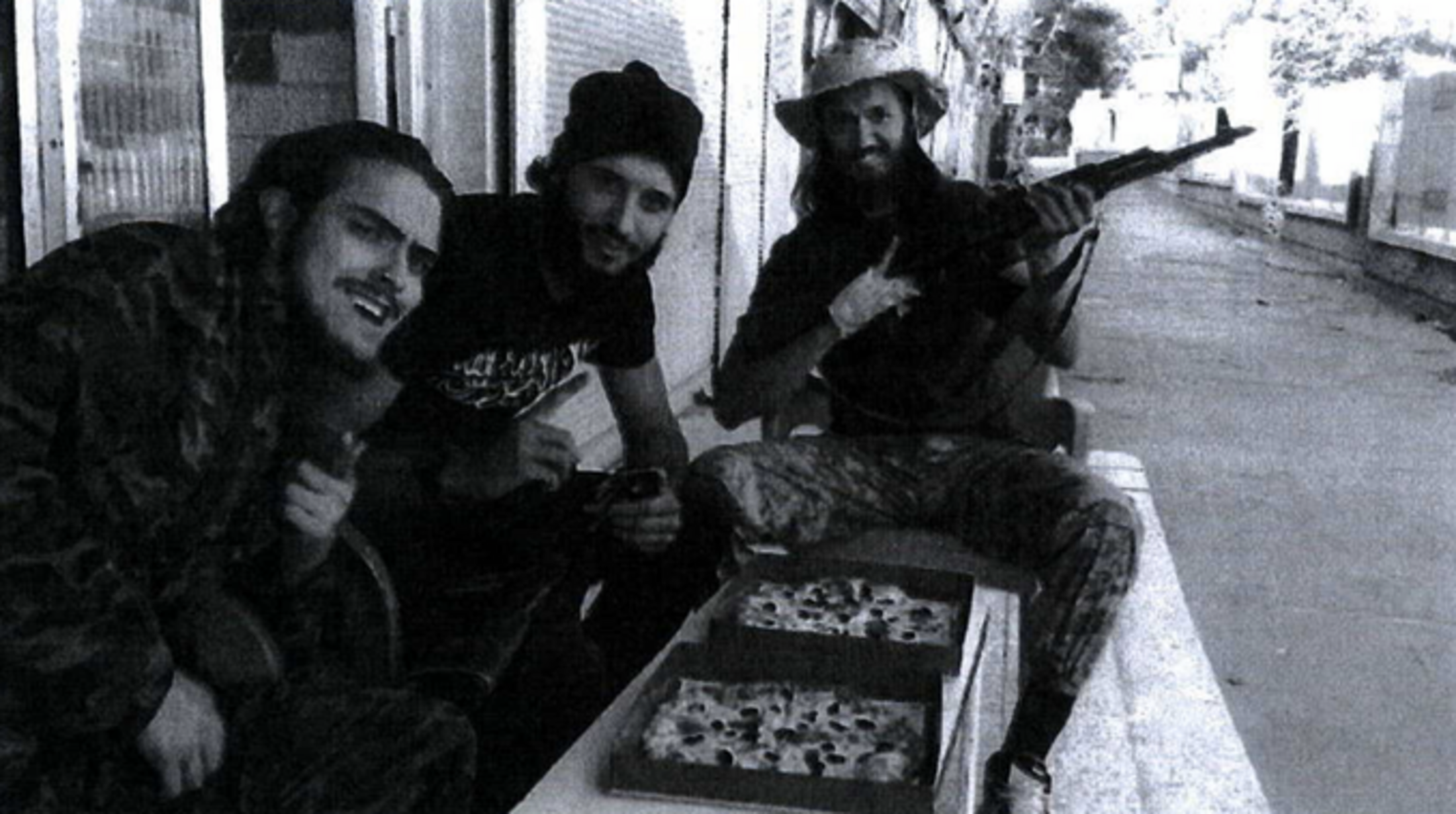

During downtime at Shaddadi, Brahim Nejara took photos and in one captured his fellow jihadists eating a pizza in a street where all the shops were closed. In the middle of the photo is Foued Mohamed-Aggad, one of the future attackers of the Bataclan music venue in Paris in November 2015.

The second noteworthy figure among the twelve condemned men is Fodil Tahar Aouidate. American surveillance had picked up Aouidate's elation in the aftermath of the November 13th attacks in Paris. And in a video he declared: “Allah had granted us the great pleasure and happiness to see these infidels suffer as we suffer here … Know that as you continue to attack us on our land, on Muslim soil, so we will continue to attack you where you are, in the heart of your capital!”

Aouidate was close to the man who coordinated the Paris attacks, Abdelhamid Abaaoud, and his case was flagged to President François Hollande at the start of 2016. The French intelligence services feared that he had taken over the role of his friend Abaaoud. As Mediapart can reveal today, it was Fodil Tahar Aouidate who was behind the so-called Strasbourg-Marseille planned attacks (members of a terrorist unit were arrested in those two cities, though in fact they had been planning to hit Paris). This thwarted plot was the last major Islamic State attack planned from its headquarters in Raqqa in Syria by the Caliphate's external operations office, the unit which organised attacks in Europe.

Whatever their role in the Middle East, the way that these French jihadists have been sentenced to death in swift succession has inevitably raised questions about the nature of Iraqi justice. Under Iraqi law someone can indeed be sentenced to death for belonging to a “terrorist” organisation, whether the accused was a combatant or not. According to the group Human Rights watch (HRW), there have been “serious flaws” in the prosecutions and it says that torture has been employed on the accused. It said: 'Human Rights Watch has documented Iraqi interrogators using a range of torture techniques, including beating suspects on the soles of their feet, internationally known as 'falaka', and waterboarding, which would not leave lasting marks on the person’s body.”

At the beginning of Fodil Tahar Aouidate's trial the judge Ahmad Mohammad rejected the allegations of torture made by the accused. “According to the medical report there are no traces of torture on his body,” the judge declared. However, according to Le Monde, Aouidate showed marks on his back to the judge who then called for a medical examination and an official forensics report.

Nabil Boudi, a lawyer defending two of those sentenced to death, including Léonard Lopez, was quoted by Le Figaro criticising what he described as “summary justice” and a “sham trial”. Lopez's hearing had lasted “no more than ten minutes”. He also criticised the absence of prosecution evidence such as telephone intercepts, photos or video surveillance to support the accusations and regretted the fact that the defence lawyers had not had access to the case files.

'Without the visible involvement of France'

Martin Pradel is one of 45 French lawyers who signed a joint article on the website of public broadcaster France Info attacking the lack of action by the French state over the death sentences pronounced against French citizens in Iraq. He does not represent any of those facing the death penalty but is involved in the defence of two French women, Mélina Boughedir and Djamila Boutoutaou, who have been sentenced to life imprisonment. He told Mediapart about his experience in Iraq. “At the current time you can't have a trial worthy of the name in that country. The situation is anything but calm,” he said.

The lawyer recalled his arrival in Baghdad and seeing the concrete tunnels that are supposed to protect houses from the blast of explosions and the six-feet high walls designed to protect people walking in the streets from snipers. “I had a very difficult time finding an Iraqi colleague who would agree to take me into in his office so that I could defend my client,” he said. “Some asked me for staggering fees of a million dollars to help them for half a day. They explain to you that it's for their family, that if they take the risk it must at least be worth their while ...” He said Iraqi lawyers live in terror. Martin Pradel did not have access to the investigation into his client. “When we were introduced to the judge the first thing that he explained to us was that his predecessor had been assassinated. Whatever the verdict that's reached, the different factions threaten the lives of the judges' families. If I sum up my stay in Baghdad, I met terrified lawyers and a hunkered down judge.”

The French lawyer said the trial itself lasted 30 minutes. “There was a reading of the charges which took around ten minutes,” said Martin Pradel. “Then two or three narrow questions to the accused which took five more minutes. Then we had to plead from a text written in advance and which could not exceed one page. Then the [court] president took his phone and left alone, without his advising judges, to deliberate. He came back after ten minutes, his phone still to his ear. He gave the sentence and it was over. ..and that is what the French government's spokesperson [editor's note, Sibeth Ndiaye] describes as a fair trial.”

France's Ministry of Foreign Affairs declared at the beginning of June that Paris was doing all it could to ensure that the French citizens escaped the death penalty. In reality, however, France is playing a double game.

The French state's General Secretariat for Defence and National Security (SGDSN) - Secrétariat Général de la Défense et de la Sécurité Nationale (SGDSN) – had previously been working towards the “repatriation of detained French citizens” and coordinated the inter-ministerial work carried out on this issue. When just before Christmas 2018, the SGDSN had submitted to the Elysée a document setting out the different options of various government departments, it had treated with scepticism the option of “our thirteen [editor's note, in fact twelve] citizens” being tried “in situ”. It warned: “The Iraqi option entails very strong cooperation on the part of this country's authorities, at a period when they have no interest in annoying the Syrian regime or Iran by helping us.” Before giving its opinion the SGDSN had consulted with France's Ministry of Foreign Affairs, the Ministry of Defence and the Ministry of the Interior.

At the time the French ministries were much more favourable to a repatriation of the French citizens carried out “from start to finish” by the Americans who would collect the jihadists in Syria and deliver them, their hands and feet chained, onto French soil. But that was before the U-turn by President Emmanuel Macron who did not dare to go against public opinion, with the polls showing strong opposition to the idea of the French jihadists returning, even to prisons in France.

As a result the idea that eventually prevailed was to have the jihadists tried in Iraq; there was no other regional option given that the Kurdish authorities in Syria who held them were not part of a state and given that France has no diplomatic relations with Damascus. The twelve former French residents were thus part of a larger group of 280 detainees handed over by the Syrian Democratic Forces to the Iraqi authorities in February 2019.

By chance the Iraqi president Barham Salih was in Paris at that time and he announced that the French jihadists expelled by the Kurds would indeed be tried in Iraq. President Macron, who stood next to his Iraqi counterpart, stonewalled all questions about their nationality and insisted that Baghdad had the “sovereign” right to decide on such procedures. It is legitimate to question, however, just how “sovereign” that decision was. In its recommendations to the French head of state two months earlier the SGDSN said that any operation to expel the jihadists to Iraq should be carried out “without the visible involvement of France” and that “our country's fingerprints” should not appear on it.

Enlargement : Illustration 3

Beyond the understandable questions about the law and morality, there are also issues over the operational effectiveness of trials in Iraq in terms of security and the prevention of further attacks in France. In all likelihood the death penalties will be commuted to life imprisonment; Baghdad has already sentenced to death more than 500 foreign jihadists for joining Islamic State and as yet none has been executed.

Meanwhile, there have been mass escapes by jihadists from Iraqi prisons in the past. Peter Chérif, a member of the so-called Buttes-Chaumont jihadist network – named after an area of north-east Paris - had initially been captured in Fallujah in Iraq in 2004. At the time an Al Qaeda fighter, he was given a 15-year jail term by the Iraqi authorities. But he did not complete it. On March 6th 2007 a raid on Badush prison in Iraq freed 150 prisoners, including Peter Chérif.

After another spell in prison – this time in France – Chérif went to Yemen and joined Al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula, and the French intelligence services suspect him there of having designated his old friends the Kouachi brothers, Saïd and Chérif Kouachi, to carry out the murderous attack on the satirical magazine Charlie Hebdo in Paris in January 2015. In theory Peter Chérif should have remained in an Iraqi prison until the following year, 2016 (he was finally arrested in Djibouti in East Africa in December 2018 and extradited to France).

On July 21st 2013 another prison raid, this time on Abu Ghraib jail on the outskirts of Baghdad, led to the escape of around 500 jihadists, some of whom went on to have senior roles inside Islamic State. As early as last year Wassim Nasr, a journalist for public broadcaster FRANCE 24 and author of L’État islamique, le Fait Accompli, published by Plon in 2016, had warned: “Agreeing to leave jihadists there like this could make the threat worse, because our intelligence services won't know where they are when they are freed.” he added: “European statesmen must accept and take decisions which don't please [public] opinion but which will bear fruit in the long term.”

But according to many observers, when it comes to the fight against terrorism, successive French governments have favoured the short-term approach.

----------------------------

If you have information of public interest you would like to pass on to Mediapart for investigation you can contact us at this email address: enquete@mediapart.fr. If you wish to send us documents for our scrutiny via our highly secure platform please go to https://www.frenchleaks.fr/ which is presented in both English and French.

--------------------------

The French version of this article can be found here.

English version by Michael Streeter