After the disruption of the Covid-19 pandemic, the Russian-led war in Ukraine has further tested the agenda for the introduction of the European Commission’s measures on climate change and notably its ambitious Green Deal programme which aims to make the European Union (EU) bloc carbon neutral by 2050.

Not least among the upsets is the rush to end dependency on Russian gas, which represents 40% of all gas consumption across the EU, with a number of member states turning for alternative natural gas supplies from North America and the Middle East, while others are reopening, or delaying the closure, of coal-fired power plants. All of which comes at a time when the European Commission wants to speed up the deployment of renewable energies and notably the development of ‘green’ hydrogen.

Meanwhile, the so-called “Farm to Fork” strategy, aimed at moving away from intensive farming in favour of an environmentalist approach, and which the Commission describes as being “at the heart of the Green Deal”, has also been adversely affected by Russia’s war against Ukraine amid fears voiced – in no small part by industrial agriculture lobbyists – over food supply shortages. As a result, fallow land along with permanent meadows and hedges classified as being of environmental interest has now been made available for production, while the presentation of the details of the “Farm to Fork” measures, including the expansion of organic farming, a reduction in the use of pesticides and chemical-based fertilisers, has been postponed to at least this summer.

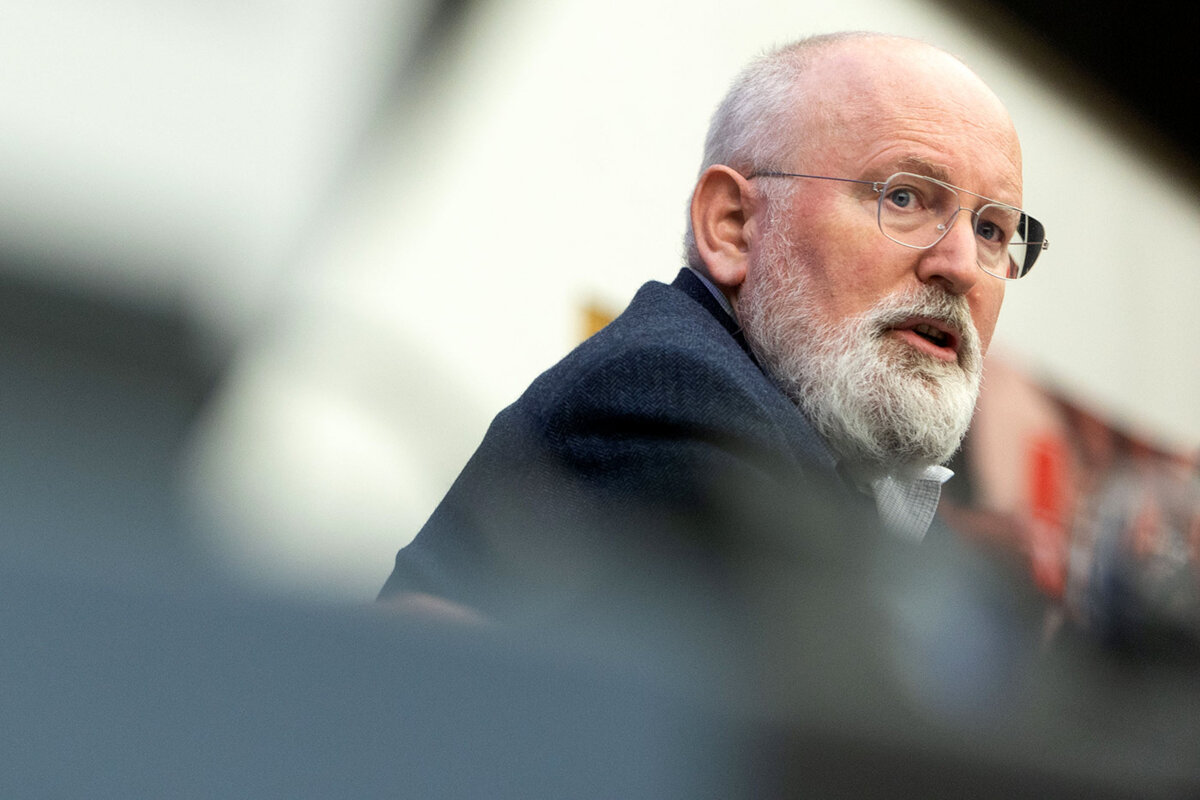

In this interview with Mediapart, Frans Timmermans, vice-president of the European Commission responsible for the Green Deal and climate change action, details the already challenging situation that has been made all the more acute since the invasion of Ukraine in February. The Dutchman, 61, calls upon political leaders across the EU to find the courage “to recognise the crisis that we are in”.

-------------------------

Mediapart: Does the war in Ukraine offer an opportunity for the European Commission’s Green agenda?

Frans Timmermans: The war in Ukraine is a tragedy. There is a Europe of before February 24th and a Europe of after. Injuries and scars are going to dictate our policies over generations. The transition towards a sustainable society has not lost its urgency – that urgency has been increased.

Mediapart: Yet the war in Ukraine has prompted some, critical of the ‘Farm to Fork Strategy’, who argue for more food security measures rather than the development of an ecological system of agricultural production. What is your view of that?

F.T.: First of all, we export massively. We also waste at least 20 percent of our production. If we reduce wastage of cereals, which represent half of Ukraine’s cereal exports, we would win back enormous quantities. Finally, when one sees to what degree our crops are used to feed animals and not humans, the system needs to be re-thought.

Mediapart: Such as reducing the amount of livestock farming?

F.T.: I’m not saying that livestock farming should be reduced, I’m simply saying that one should not use the argument that there would be shortage of food in Europe and to ask for more [farming] surfaces whereas they are almost exclusively destined for animal rearing. There are problems with food prices, I don’t deny that. But there will be no famine in Europe because of the war in Ukraine.

Enlargement : Illustration 1

Mediapart: Does that mean that the return to production of fallow land, which was decided one month after the Russian invasion, was not necessary?

F.T.: That was not my proposal. It is a decision by the EU Council and of [the European] Parliament, and I understand that this eases some fears. I said to the parliamentarians, food security and the supplies for the European Union are not threatened by the Russian invasion of Ukraine. I was attacked for that by Christiane Lambert, the president of the European agricultural [EU farmers’ representative] body, the COPA-COGECA. According to her, what I said was ‘shameful’ and ‘inhuman’. To use such terms shows one doesn’t have concrete arguments.

It’s interesting to note that the debate is not the same with the ‘Fit for 55’ package [editor’s note, a programme to cut current greenhouse gas emissions by at least 55% by 2030]. Everyone is convinced that, with this war, the energy transition must be speeded up.

My argument is that we must strengthen our food sovereignty. That can only happen with a sustainable system. It doesn’t mean raising production volumes under unacceptable social and ecological conditions, but rather to be more independent of the chemicals industry and to meet citizens’ demands.

For 40 or 50 years, the COPA-COGECA and those around it have been used to having an exclusive domain; all those who are not part of the system, who have the audacity to have an opinion about it, should be quiet. But I want to engage with them, I want cooperate, above all with farmers because there are many of them who want to change direction.

Mediapart: Already, before the war in Ukraine, the COPA-COGECA and other agribusiness bodies did all they could so that members of the European Parliament voted against the ‘Farm to Fork’ strategy which, they argue, would lead to a significant fall of the continent’s agricultural production. They notably referred to a study by the European Commission’s scientific services which predict a fall of between ten and 15 percent. Do you share that view?

F.T.: No. There are also other studies. Kiel university, for example, came to different conclusions [editor’s note, see more here and here]. In any case, we cannot continue with the current CAP [Common Agricultural Policy]. Droughts already cause us enormous problems, as do the loss of biodiversity and a lack of pollinators. We are in a crisis situation. ‘Farm to Fork’ helps us to solve that and leads to a more favourable situation for farmers.

Mediapart: In what way?

F.T.: For the first time we have a comprehensive approach which targets production but also the behaviour of consumers. Certainly, a proper remuneration for the work of farmers remains an issue, but an increase in intensive farming would provide no help at all on that front.

They must be given another role; be allowed to produce food that is recognised by consumers as being of high quality, rewarded for the protection of nature, remunerated for capturing CO2 in the ground. All of this will bring another foundation for their economic security.

One should not just consider the interests of the large agricultural businesses. Agriculture in Europe will either be tenable and sustainable, or it won’t be. To hold on to a system of production which struggles to offer sufficient income to farmers while knowing that this system cannot last is irresponsible. One must have the audacity to propose an alternative.

Mediapart: COPA-COGECA is not alone in lobbying against the ‘Farm to Fork’ strategy. Several EU member states are reticent about it, including France, whose agriculture minister, Julien Denormandie, is against it. During his re-election campaign, President Emmanuel Macron criticised it on several occasions.

There are a certain number of resistances to it since you have tried to advance with this agenda. Who, in fact, are your opponents – the agribusiness lobby, or the member states, or the Commission’s directorate-general for Agriculture and Rural Development?

F.T.: I call upon political leaders’ courage to recognise the crisis that we are in. It’s easy to leave things the way they are – no conflict with the big agricultural organisations, no electoral problems. What I hope for today is to open up a dialogue with the next French government in order to get into the details of our proposal.

‘Farm to Fork’ will not lead to a rise in prices nor a drop in agricultural production. I want at least to have the possibility to demonstrate this. In the last days of his [election] campaign, the French president re-declared himself to be an environmentalist. Let’s see what that means for the programme of the [new] French government.

Mediapart: That was to attract a certain electorate.

F.T.: Certainly, but maybe he also attacked ‘Farm to Fork’ to attract another electorate. We’ll see what that brings on balance when there will be a government.

It must be understood that agriculture concerns all of society. It is for that reason that we have elaborated this policy. The industrialists use the argument of farmers’ well-being to, in reality, make enormous profits. The challenge for us is to be the ally of farms, and not only of those who represent them.

Mediapart: The first concrete step in this agricultural roadmap will be the publication in June by the European Commission of a new directive on the use of pesticides. An early version of the text, leaked in February, was strongly criticised by European environmentalist NGOs over its lack of constraints and fixed objectives, which were left to the discretion of member states. Has the text of the directive evolved since?

F.T.: Yes. We haven’t yet finished our work. These new regulations are necessary because the loss of biodiversity is beginning to cause enormous harm, not only for nature but also for agriculture. My aim is to have a binding proposal.

Enlargement : Illustration 2

Mediapart: Does ‘constraining’ mean there will be the possibility of applying fines on member states which do not meet the objectives, and how can we concretely achieve a 50 percent reduction in the use of pesticides by 2030, as announced by the European Commission?

F.T.: It’s too early to say. We are in the process of preparing the text within the Commission’s services.

Mediapart: Is it the aim that, ultimately, the European Union would stop using pesticides altogether?

F.T.: We must reduce pesticides, we cannot do away with them. We must also modernise agriculture, using digital means to target with greater precision the use of pesticides, and developing other products that are nature-friendly. It is not only about defining the products that will be used; we are setting in motion a system change.

Mediapart: Another major subject in the European Green Deal is that of energy. The plan to make Europe’s energy consumption ultimately independent of Russian fossil fuels, as announced by the Commission on March 8th, includes an acceleration of the deployment of renewable energies.

But Italy has raised the possibility of reopening coal-fired power plants, while in France, state-backed utility company Engie has just signed deals for the supply until 2041 of liquified natural gas from the US. Meanwhile, Denmark has authorised the reopening of construction work on a pipeline carrying natural gas from Norway to Poland.

Is Europe not in the process of taking a big step backwards on climate change goals and which may derail the ‘Fit for 55’ programme agenda?

F.T.: One must have a holistic approach to this challenge. It is impossible to immediately replace all the Russian hydrocarbons with sustainable energy. Alternative energy sources must be found, and LNG [Liquified Natural Gas] is one of them.

The latter entails new infrastructures. In this respect, the Germans have announced the construction of new LNG terminals. Meanwhile, there are terminals in Spain that are under-used because the construction of the necessary infrastructure in France would be too costly – but I hope that the context will push France to change its opinion.

These infrastructures must be made to contribute to a true solidarity between member states because we still cannot easily supply each other within the EU in the event of a shortage.

These new infrastructures must also be prepared to transport renewable energies, notably hydrogen. If we manage this, the conversion of gas pipelines for [delivering] hydrogen can be carried out at just 25 percent of the cost of building a whole new hydrogen network.

Finally, getting rid of Russian fossil fuels means negotiating with other states, because the EU cannot replace its dependency upon one country with another.

The United States has already promised us a further 15 billion cubic metres of LNG, which will in the end become 50 billion cubic metres in the coming years. [Editor’s note, the EU imported around 155 billion cubic metres of natural gas from Russia in 2021].

Lastly, I was [recently] in Egypt and Turkey with a double proposition; firstly, that of being able to buy their gas, secondly that of including them in our long-term European strategy for green hydrogen . These producer-nations know that the market for hydrocarbons will disappear, and that they will have to therefore develop another economic base. And most among them regard photovoltaics, wind turbines and also green hydrogen production as a plus for their economy. We will never be in a position [ourselves] to produce enough green hydrogen for our industries. So, the idea is to build a strategic alliance with them so that they have access to our technology for green hydrogen and access to European markets. These countries will produce an excess supply of electricity that they can export to Europe, knowing that this electricity can also be stored thanks to green hydrogen.

Enlargement : Illustration 3

Mediapart: You talk a lot about LNG and green hydrogen, but the United Nations argues that gas production must be reduced by three percent per year between now and 2030 in order to limit global warming to 1.5°C. In Europe, more than 90 percent of hydrogen production is from fossil gas sources. Is not the EU closing itself into a future of fossil gas-based energy, using the pretext, as industrialists falsely claim, that gas represents a ‘transition energy’?

F.T.: There is indeed always that risk. But there is another lever which one must use; accelerating the deployment of renewable energies. The potential of rooftop solar remains enormously underestimated, whereas we can develop it very quickly. From a regulatory point of view, it’s not too complex to put in place.

The problem is rather the question of being able to produce enough solar panels in the EU and to find the workforce to install them. We are working on that with [internal market commissioner] Thierry Breton, as these products are today mostly imported from China.

We also have considerable possibilities to double production of biomethane, thanks to agricultural methanation units.

Finally, we must consume less energy. I do not shy away from an appeal to the individual behaviour of Europeans, and setting the right example. A [temperature] reduction of 1°C in our buildings is equivalent to saving 10 billion cubic metres of gas. Doubling the energy renovation of our buildings would save us 20 billion cubic metres of gas per year. And at the same time, it would strongly reduce our bills!

Mediapart: Sobriety, then, is not a taboo word for you?

F.T.: For me, no. It is also a convincing way to mobilise European citizens in solidarity with Ukraine, because this money stays in Europe and doesn’t end up in the pockets of Vladimir Putin [editor’s note, the EU spends about 700 million euros per day on Russian fossil fuel supplies]. If millions of Europeans took this small step, it would be a leap ahead for all of society.

We live in an individualistic, pessimist society and we are too often wary of others, but if we can demonstrate in this complex crisis situation that solidarity is not a vain word, and that it can concretely be put in place, it can give us an incredible energy.

Mediapart: Not all member states are committed in the same way to ending the use of fossil fuels. Poland, which is the European country that is most exposed to the war in Ukraine, remains the continent’s largest coal producer, and depends on Gazprom for 50 percent of its gas consumption. What does the European Commission propose so that Poland can turn away from both these fossil fuels?

F.T.: Polish leaders have committed themselves to ending the use of coal. That will not change. It is the timetable that is subject of discussion. Poland, moreover, receives enormous support from the EU to carry out this transition.

To end coal consumption, the Poles had planned to use gas as a transition fuel. Now, for understandable reasons, they prefer to limit that phase. So, they want to use coal for a bit longer than foreseen. That’s possible if we move much faster on the introduction of renewable energies. We can keep the same targets. We’re developing models for that.

Mediapart: In the coming days, the European Parliament is to discuss the reform of the European carbon market in the energy, industrial and air transport sectors, in order to adjust to the Paris Climate Accords. This will have an impact on the cost of vehicle fuel and domestic fuel and gas. It is a reform that will particularly affect financially insecure households.

F.T.: The rise in the energy costs first of all benefits Russia and the energy industrialists who currently make incredible profits. I do not understand why these profits are not subject to a supplementary tax – although that decision is not for the European Commission to make, but rather for the member states.

The political question to which one must respond is this: how does one redistribute the money levied from the CO2 market? Member states already have, with the current carbon market, the possibility of using this money to help those in difficulty with their energy costs. It is a question of political choices at the level of states themselves.

That is also how I view the future Social Climate Fund. Our intention is to put it into place before introducing the carbon market for transport and housing sectors.

The current rise in energy prices leads to profits that leave Europe, whereas a carbon market with a just system of distribution allows for pan-European solidarity and extra financial support for the transition towards renewable energies.

Some northern member states are strongly in favour of a carbon market for transport and housing, but they do not want the creation of a Social Climate Fund. Others want the opposite. Both are indispensable. We need a transparent and just system for citizens who have heavy energy bills to pay.

Mediapart: When will the EU put an end to the free carbon emissions quotas that are, since 2005, granted to European industrialists to allow them to compete with those from countries without such constraining regulations? According to the WWF, around 67 billion euros were lost over the period between 2013 and 2018 in the form of permits to pollute that were freely distributed to heavy industries. Member states are very divided on this issue.

F.T.: We are advancing towards a solution, both in the EU Council and in Parliament. The carbon border tax can only fully function if there is, little by little, a reduction in free quotas.

Mediapart: The lobbying by industrial businesses in this case must be quite something?

F.T.: Yes, although the latter are divided. There are those who are afraid for their economic survival, and others who have understood and have already moved into the future.

What we are asking for is difficult but not impossible. The competitive advantage with the future carbon border tax is enormous for Europe, they know it. Two years ago, the carmaking industry called me mad. Since then, we have all taken the same path – a complete transition to zero-emission cars between now and 2035.

-------------------------

- The above interview was conducted in French, the original text of which can be found here.

English version by Graham Tearse