Barely a week after France and its former colony Algeria began easing their strained relations, renewed tensions have erupted between the two countries and brought the prospect of dialogue to all but a close.

The disagreement was this time sparked over the placing under investigation in France – a legal step which is one step short of charges being brought – of an Algerian consular official who is suspected of having participated in the kidnapping and detention of an opponent of the Algerian government living in exile in France. The opponent, an influencer with the adopted name of Amir DZ, was eventually released unharmed.

“This inadmissible and unspeakable new development will cause great damage to relations,” read a statement released by the Algerian foreign affairs ministry. Summoning the French ambassador in Algiers, the ministry reacted to what it called an “undignified” act by announcing on April 13th the expulsion of 12 French officials who were given 48 hours to leave the country. It was a rare move in the history of diplomatic relations between the two countries.

The tensions between France and Algeria rose dramatically last year when French President Emmanuel Macron announced the recognition of Moroccan sovereignty over the disputed Western Sahara region, where Algeria, in open conflict with Morocco, supports the pro-independence Polisario Front.

Those tensions were heightened when, in November last year, Algeria arrested French-Algerian novelist Boualem Sansal, 75, accused of national security offences for questioning the veracity of Algeria’s borders. He was handed a five-year jail sentence.

But overshadowing everything in French-Algerian relations is the bitter history of French colonial rule over the north African country, which began in 1830 and ended, after a murderous eight-year war of independence, in 1962.

A statement issued on Tuesday this week by the French presidential office, the Élysée Palace, said Algeria bears “the responsibility for a brutal deterioration [of] bilateral relations”, describing the move by Algiers as unjustified and incomprehensible”. On April 15th, the Élysée announced that France was taking action “symmetrically”, with the tit-for-tat expulsion of “12 officials serving in the Algerian consular and diplomatic network in France”, adding that Macron had decided to “recall for consultations” France’s ambassador to Algeria, Stéphane Romatet.

“In this difficult context France will defend its interests and continue to demand that Algeria fully respects its obligations with regard to [France], particularly concerning our national security and cooperation in migratory issues,” the Élysée said. “These demands stand alongside the ambition that France will continue to have for its relations with Algeria, given its interests, its history and the human links that exist between our two countries.”

Speaking off the record, a French presidential adviser commented: “In reality, Algeria has no wish for things to improve between our two countries.”

On Tuesday morning, French foreign affairs minister Jean-Noël Barrot criticised a “very regrettable decision” by Algiers. Interviewed by public television channel France 2, the minister warned that the Algerian decision to expel the French diplomats would not be “without consequences”, and said it “compromises the dialogue that has begun”.

“There remain a few hours for the Algerian authorities to reverse their decision”, Barrot added, saying France was otherwise “ready to respond with the greatest firmness”.

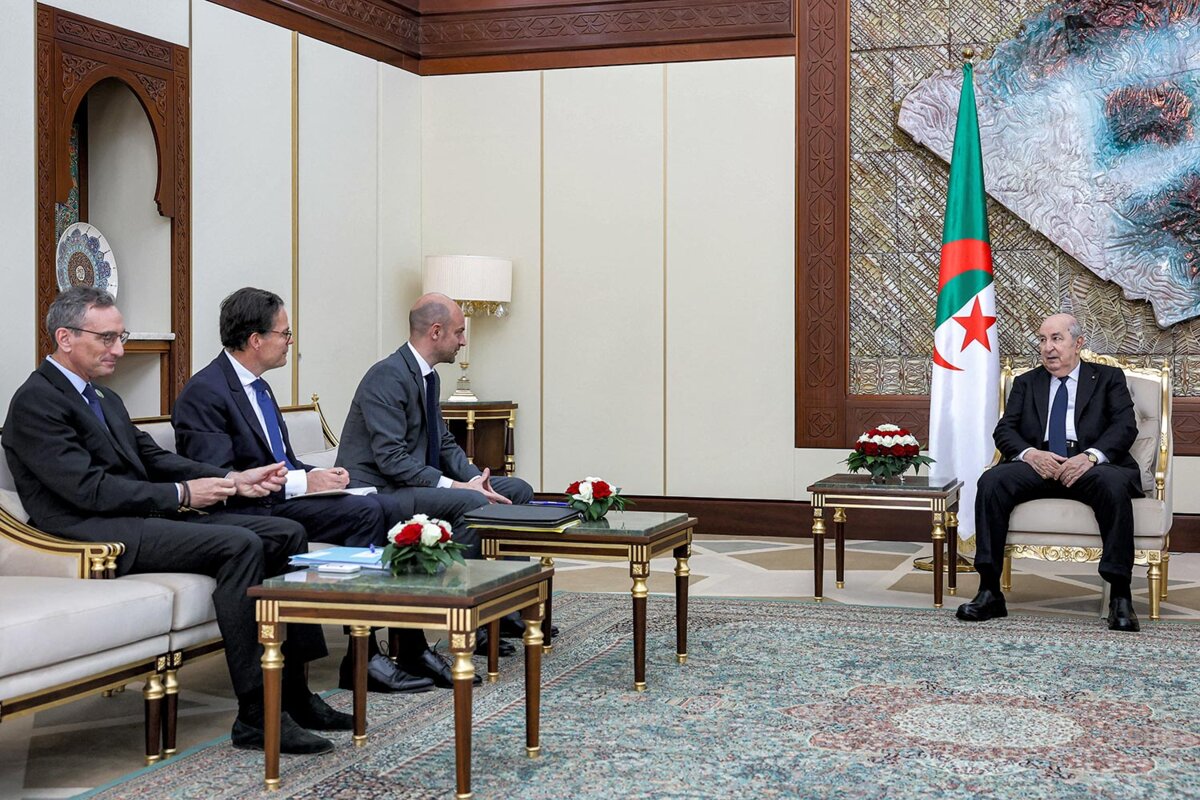

Enlargement : Illustration 1

The French Right and far-right took the opportunity to scoff at Barrot’s meeting on April 6th in Algiers with President Abdelmadjid Tebboune, which marked the beginning of a thaw in the previous crisis between the two countries. In a post on social media platform X, Jordan Bardella, chairman of the far-right Rassemblement National party, mocked “the brilliant results […] of Jean-Noël Barrot’s prostration in Algiers”. Meanwhile, Laurent Wauquiez, a Member of Parliament (MP) who is preparing a bid to become leader of the conservative Les Républicains party in competition with hardline interior minister Bruno Retailleau, targeted the minister with his own post on X. “There’s what the flexible response has brought us: a new humiliation,” he wrote. “Now, it’s for the government to defend France’s honour and to force Algeria to at last take in all its OQTFs,” he added, referring to those Algerians served with a deportation order. The refusal by Algiers in March to accept the return of around 60 of its nationals served with OQTF deportation orders led Retailleau, with Macron’s blessing, to announce France would adopt a “flexible response”, ranging from a reduction in visas granted to Algerians and even a possible temporary ban from its territory on Algerian air and maritime traffic.

Bruno Retailleau in the crosshairs of Algiers

Reading the very codified language of diplomatic tensions, amid the current tensions there is nevertheless a will on both sides of the Mediterranean to leave a door open for a de-escalation. With that in mind, Algeria has concentrated its attacks on interior minister Ratailleau in order to best preserve the recent improvement in exchanges with the French presidency and the foreign affairs ministry. For the Algerian foreign affairs ministry, Retailleau, it said in a statement, “carries full responsibility for the turn of events in relations between Algeria and France”.

Algiers accuses Retailleau of “a flagant lack of political discernment”, of carrying out unofficial, shady operations “for purely personal ends” (a reference to his political ambitions), and of seeking to “belittle Algeria”, a country towards which he shows a “negative, pathetic and constant attitude”.

Similarly, the 12 French officials ordered to leave Algeria are not from the diplomatic corps but are civil servants from the interior ministry. All of which the French foreign affairs ministry was obviously took note of. While Jean-Noël Barrot has defended his interior ministry colleague, saying Retailleau had “nothing to do” with the placing under investigation of the Algerian consular official – a move that is decided only by a magistrate – he has carefully weighed his words. “The number one principle of diplomacy,” said Barrot, “is that one must always give dialogue a chance. Those who say the opposite are irresponsible.” Even the Élysée Palace, in its statement on Tuesday, left the door open to discussion.

The only channel of confidence between Paris and Algiers appears to be that linking Macron and Tebboune. “He is my alter ego,” the Algerian president said of Macron in a television interview broadcast in Algeria at the end of March. “We’ve had our ‘sirocco’ moments, moments of strain, but it’s with him that I work.” At the height of bilateral tensions, before the most recent developments, it was through direct contact between the two that a meaningful dialogue was re-engaged.

While Macron’s North Africa advisor, Anne-Claire Legendre, made three trips to Algeria in early 2025, demonstrating the respect that Tebboune and his chief of staff Boualem Boualem have for her, the degree of confidence between Tebboune and Macron is not shared by the rest of the Algerian state apparatus.

Enlargement : Illustration 2

In the background, others are pushing for closer economic ties between the two countries. An example is Rodolphe Saadé, the French-Lebanese chairman of the giant CMA CGM transport logistics group, owner of French TV channel BFMTV, and who is close to Emmanuel Macron. He was on Tuesday this week in Algeria to discuss future large commercial agreements which, according to online newsletter Africa Intelligence, could make him the “major private actor in maritime freight in Algeria”.

France overestimating its perceived upper hand

Behind the scenes, the French government and presidency are wary of the Algerian authorities, regarded as old fashioned and weighted down by formalities. A the Élysée, what is regarded as the goodwill of Tebboune is seen as on a collision course with the omnipotence of Algeria’s military, who are reticent towards renewing relations with France. “It will never work with them,” commented a French minister, off the record, who is close to the efforts to open up dialogue.

On the diplomatic front, it is possible, if not probable, that the current spat will eventually be defused. But re-establishing French-Algerian relations may falter because of a fundamental misunderstanding.

France believes the balance of power is in its favour. It sees Algeria as isolated in the region, due to its open conflict with Morocco and also, as of recently, with the West African military juntas in Mali, Niger and Burkina Faso.

The French authorities also regard the introduction of visa restrictions for Algerian dignitaries, part of Retailleau’s “flexible response”, have hit hard those who have children enrolled in education in France, or who have second homes in the country. Furthermore, from the point of view of Algiers, the repercussions of the crisis for Algerian nationals living in France would be particularly harmful.

For all those reasons, the French authorities judge that re-establishing bilateral relations is more urgent for Algiers, which explains why France has shown little enthusiasm to make significant gestures of reconciliation, whether they be memorial, economic or strategic. The most telling example is the issue of the Western Sahara; Macron has made clear that his support for Morocco’s claim of sovereignty over the region is irreversible. “Algeria knows it has lost in this case,” commented a diplomatic source.

But by pushing its perceived advantage so far, France is taking the risk of a profound collapse of bilateral relations. President Abdelmadjid Tebboune is a connoisseur of French political life; Macron has just two years left as president (under the French constitution, he cannot stand for a third term) and his camp is subjected to the ever more pressing demands of the conservative Right and a far-right that continues to progress.

The personal stakes in the current crisis are the same for both Macron and Tebboune, namely what will be the mark they leave in the long history of relations between the two countries. Algeria could be tempted to let those relations stagnate until the next presidential election, which is often the occasion to pick up again with dialogue. Italy, Turkey and Russia, already on very good terms with Algiers, would most certainly grab the opportunity of stepping into such a diplomatic breach.

-------------------------

- The original French version of this article can be found here.

English version by Graham Tearse