Corruption, for many people, evokes personal enrichment, individual privileges and suitcases of cash. But few think about the consequences it has upon society.

In the same manner, the subject of improper practices in football will, for most, be symbolised by astronomical salaries, tricky agents and high financial stakes. Some might also evoke how a small number of cunning or talented people amass great wealth, while supporters of the game, who represent the lifeblood of the sport, find it hard to stump up the money for a season or match ticket, or for a club shirt.

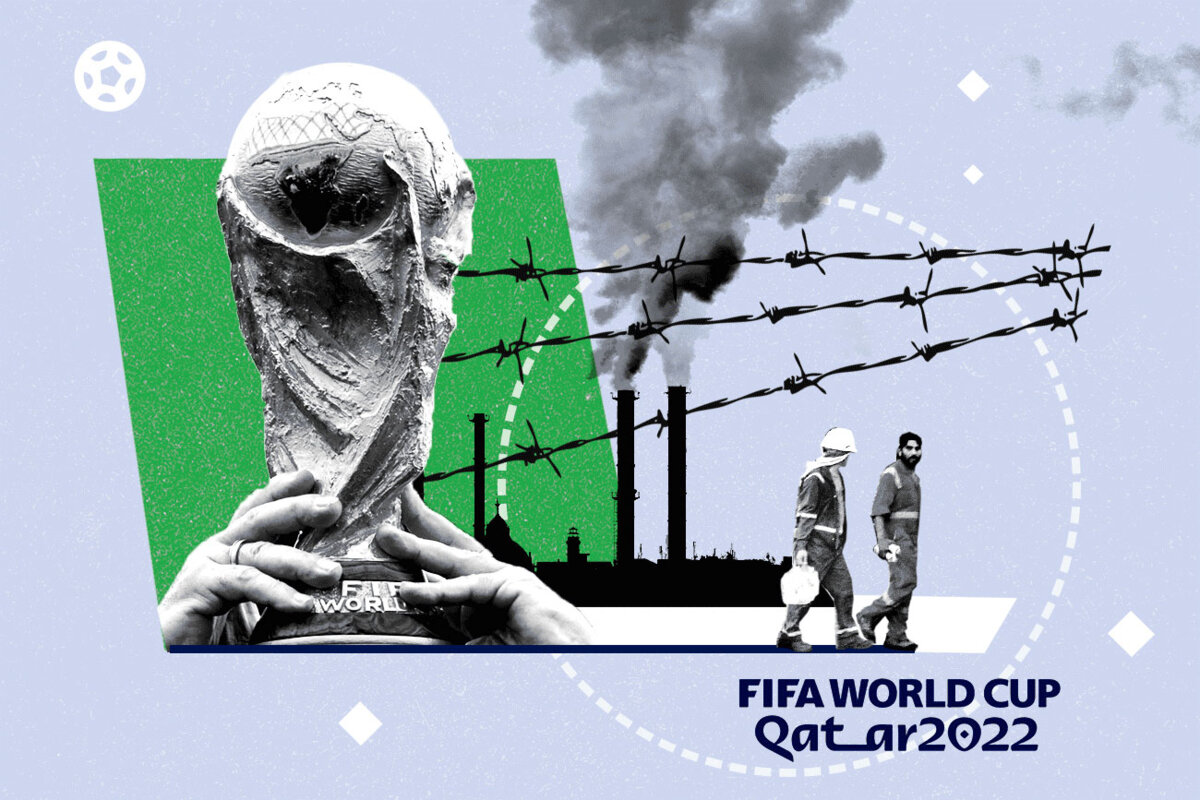

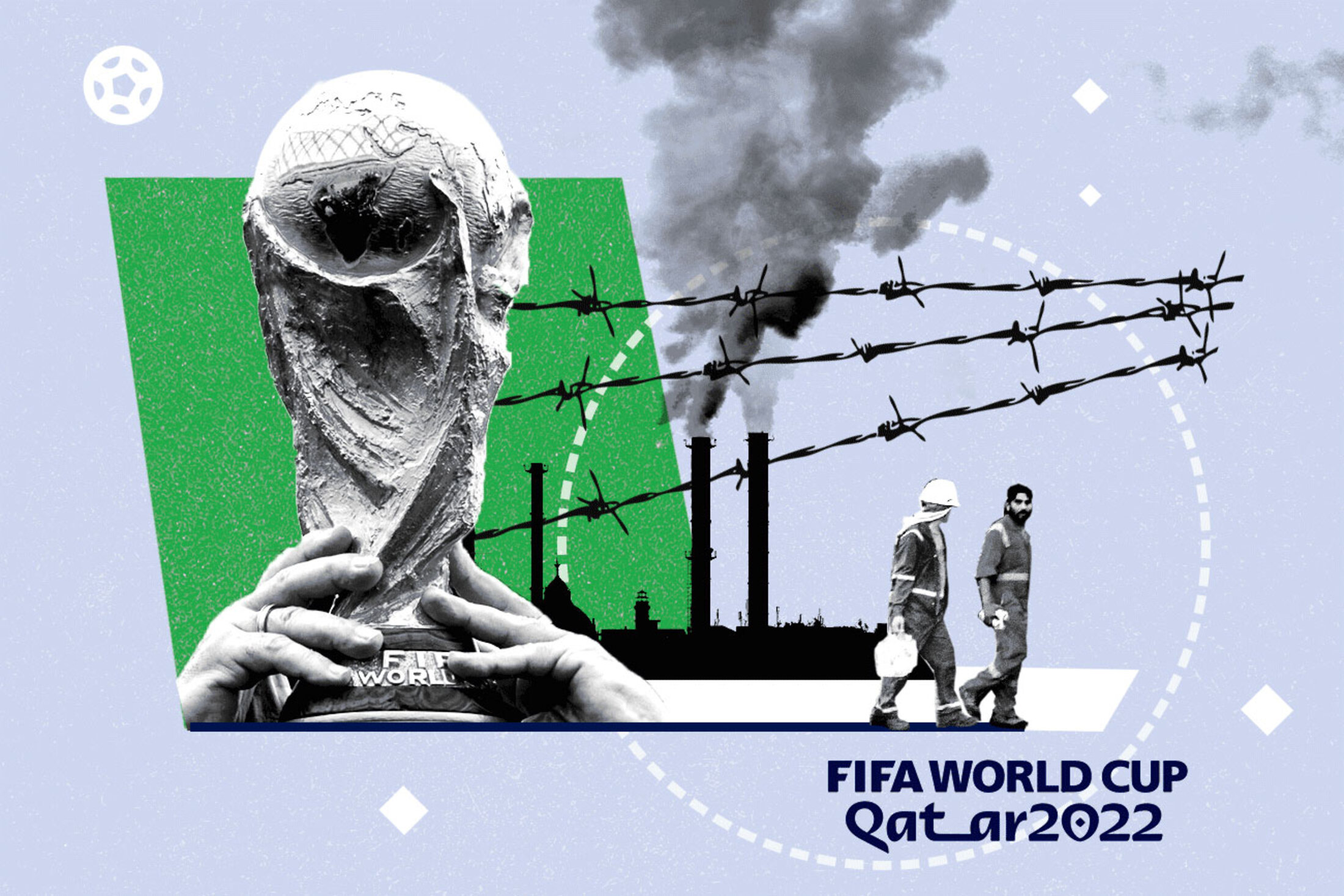

But what this World Cup in Qatar reveals with startling clarity is how shady deals have greater and graver consequences than individual profit alone. During the now notorious November 2010 lunch at the Élysée Palace, the French presidential office, when, among other things, the awarding to Qatar of the World Cup and the purchase by Qatar of the Paris Saint-Germain football club (PSG) were played out, were those then present aware of the terrible spiral into which they had launched the Gulf state?

Had Michel Platini, then boss of European football governing body UEFA, the then French president Nicolas Sarkozy and his chief of staff at the time, Claude Guéant, imagined that by promoting Qatar’s candidature, they would indirectly cause the deaths of thousands of workers engaged in building the new stadiums? Did they consider the disastrous climate effects that the tournament would create? What’s more, all of this was joined by a calamitous political signal: if a Panini sticker album of authoritarian regimes existed, the badge of Qatar would be shining high up among them.

Since the awarding of the World Cup to Qatar, Mediapart has documented these and many other issues. To read, re-read or simply sample that coverage, as highlighted in this summary, provides an insight into the scale of this scandal, in which France played a central role. Because, contrary to what President Emmanuel Macron declared last week, it is today impossible to distinguish sport from politics.

Firstly, it should be remembered that the awarding of the World Cup to Qatar was not an isolated event. Nasser Al-Khelaifi, the president of PSG and chairman of the BeIN Media Group, was formally placed under investigation in France for “active corruption” in relation to Doha’s bid to host the athletics world championship. During the bidding process in 2011, a company he and his brother owned paid 3.5 million dollars to the son of the then president of the International Association of Athletics Federations (IAAF).

In June 2020 Mediapart revealed the extracts of phone text messages that showed how Jérôme Valcke, then secretary general of FIFA, the international governing body of association football responsible for the World CUP, was in 2015 gifted with a luxury watch worth 40,000 euros just after a crucial vote in favour of holding the tournament in Qatar in the winter, in an extraordinary move from its traditional summertime date. A Swiss court eventually aquitted the two men of charges related to bribery, which included Valcke’s free use of a luxurious villa owned by Khelaifi in Sardinia.

Enlargement : Illustration 1

In France, there is a long list of coincidences which have attracted the interest of anti-corruption police. Over the years, it emerged that following his failed re-election bid in 2012, Nicolas Sarkozy personally benefitted from the support of Qatar in his return to private affairs. After his election defeat, he went back to practicing as a lawyer with his legal firm Claude & Sarkozy (later renamed Realyze), and was handed separate contracts by two high-flying French businessmen friends of his.

One was Arnaud Lagardère, whose Lagardère Group hired Sarkozy’s services six months after a Qatari investment fund became its principal shareholder; the other was Sébastien Bazin, chairman and CEO of French hotel and leisure group Accor and who was the boss of PSG until it was sold to the Qataris. In December 2015, the Qatari sovereign fund QIA became the second largest shareholder in the Accor group.

In September this year, Mediapart revealed how, in 2011, several months after Qatar was awarded the hosting of the 2022 World Cup, Sarkozy, via Claude Guéant, approached the Gulf state’s rulers to ask that they hire the services of PR consultant François de La Brosse who had never been paid for work he did for Sarkozy during the latter’s 2007 election campaign and also later, when Sarkozy was president (see the report, in French, here).

The Sunday Times recently revealed that Mediapart journalist Yann Philippin, who has led most of Mediapart’s investigations into the awarding of the 2022 World Cup, was targeted by a gang of hackers hired to spy on journalists and other individuals “who threatened to expose wrongdoing” over Qatar’s hosting of the tournament. It was only Philippin’s vigilance that thwarted a very sophisticated attempt to hack into his documents and email communications.

Meanwhile, in an article published this weekend, Mediapart has detailed how Nasser Al-Khelaifi, fearing a police raid on his premises in 2017, ordered his major-domo to urgently collect and destroy potentially compromising documents.

Workers exploited, environmental concerns disregarded

The conditions in which Qatar was awarded the hosting of the 2022 World Cup is not the only subject of interest surrounding the tournament, for the consequences of this are also disturbing, beginning with the creation of the infrastructures necessary for the games. This has involved the forced and even unpaid labour of a battalion of migrant workers, assigned to building the sites at an infernal rhythm and amid extreme heat (see Mediapart’s photo reportage, in French, on the migrant workers who succeeded in obtaining the right to play football once per week – on their day off).

Thousands of them have died (The Guardian has estimated a death toll of 6,500 since the construction work began), although it is impossible to place an exact figure on the number of victims. Vinci Construction Grands Projets, a subsidiary of French construction and concessions group Vinci, was this month placed under investigation in France for “forced labour” and “reduction to servitude” at its sites in Qatar.

But there are also consequences yet to come. Seven out of the eight stadiums that have been built are air-conditioned, an absurdity from the point of view of energy consumption. Furthermore, during the tournament an average of one passenger plane every ten minutes will transport supporters between Qatar and neighbouring countries; every day, more than 160 low-cost flights will be made available for supporters from countries close to the Gulf state to attend matches.

Qatar’s pledge that the tournament will be carbon-neutral is simply not credible, as Vincent Viguié, a researcher and lecturer specialised in the economics of policies to curb climate change, explained in a special edition this month of Mediapart’s regular video discussion programme 'À l’air libre', which explores in greater depth the issues raised above.

-------------------------

- The original French version of this article can be found here.

English version by Graham Tearse