Mediapart has obtained access to the contents of internal documents from French aircraft manufacturer Dassault Aviation, designer and maker of the Rafale fighter plane and the Falcon business jet, which advises its staff on how to respond, and notably how to avoid directly answering, prickly questions over its activities, notably its weapons exports to “dictatorships” and sales of private jets for the wealthy few who leave outsized carbon footprints.

The documents seen by Mediapart are addressed to members of staff called “ambassador-teachers” who take part in presenting their work and professional experiences to students of engineering schools, part of the elite establishments known as “les grandes écoles”, and university institutes of technology, or IUTs. While the representatives provide budding engineers a real-world insight into the aviation industry, the bonus for Dassault Aviation is to encourage and identify potential future recruits.

But at a time when higher education students and graduates are increasingly questioning the sense of their professional paths, amid a trend to turn away from industry (see this discussion forum, in French, on Mediapart) and heightened concern over environmental issues, it is hardly an ideal climate for Dassault to promote the attractivity of its business, largely based on selling combat aircraft, notably to authoritarian regimes, and private jets to the super-rich.

The company has come in for sharp criticism from some quarters for its sales of Rafale jets to the Egyptian regime of President Abdel Fattah El-Sisi, which practices torture, extra-judicial executions and mass arrests of opponents, to the United Arab Emirates (accused of committing war crimes in Yemen), and over its dealings with Qatar (the sale of 24 Rafale jets is under scrutiny in a French judicial investigation into suspected corruption).

Meanwhile, Dassault, whose sales of Falcon business jets in 2021 represented 27% of the company’s turnover, is also sucked into the growing controversy over the use of such aircraft whose vast carbon footprint per traveller, in comparison to regular passenger planes, let alone rail transport, has seen their owners named and shamed on social media and tracking websites.

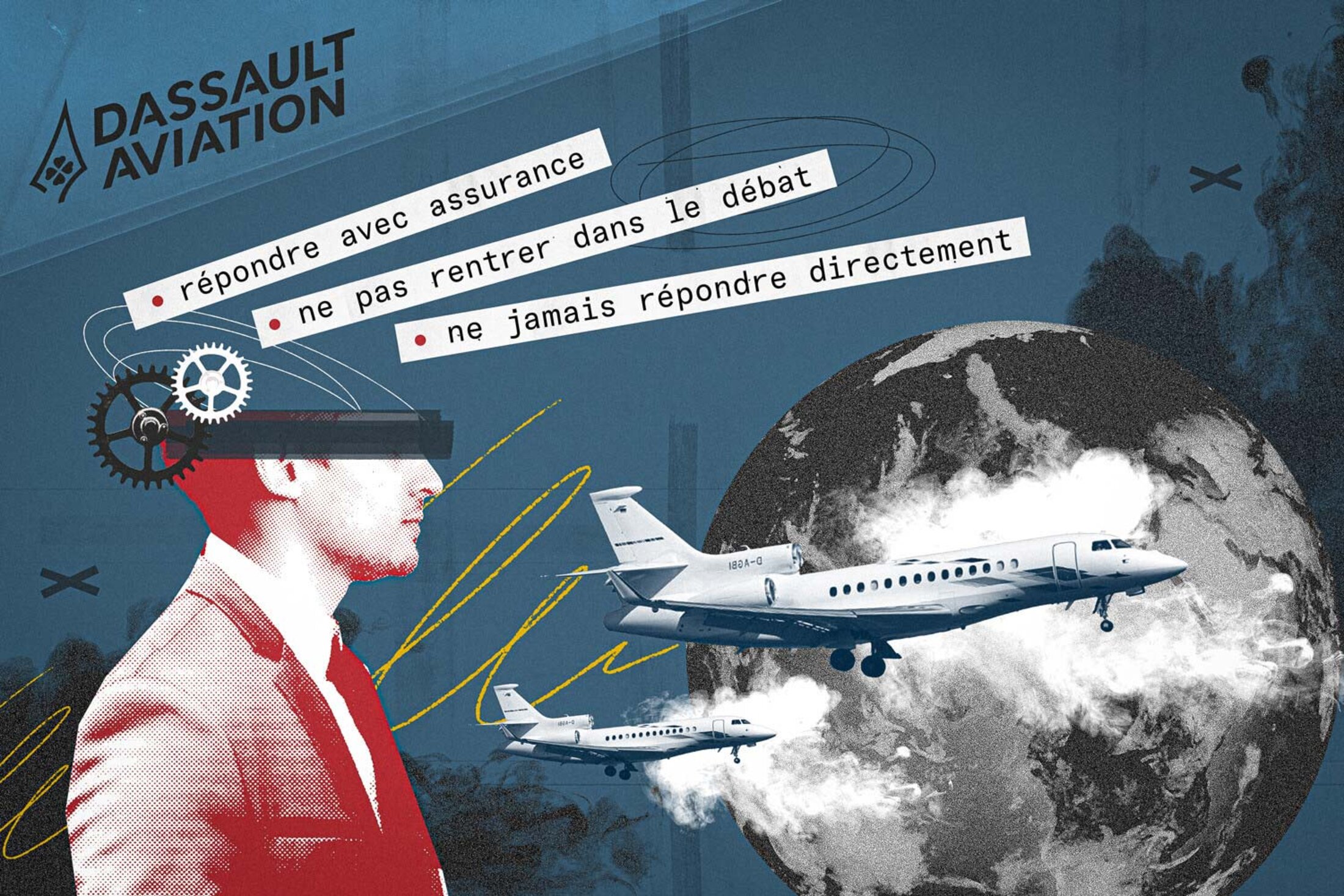

Enlargement : Illustration 1

In face of the potentially awkward questions that might be put to its “ambassador-teachers” during their presentations to students, the company this month gave them, for the start of the new academic year, a series of documents with instructions on what to expect to be asked, how to react, and set phrases to use in response, called “éléments de langage” (elements of language).

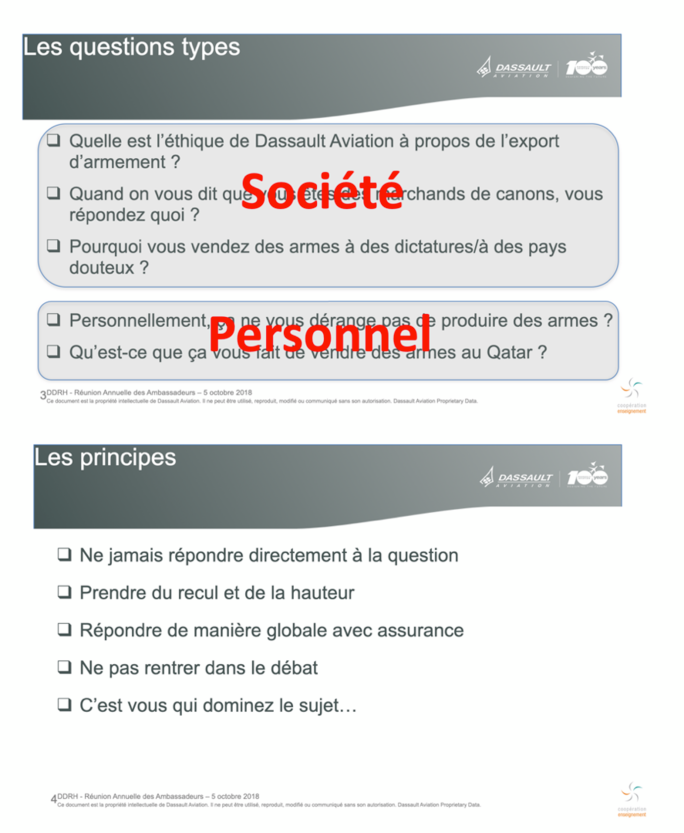

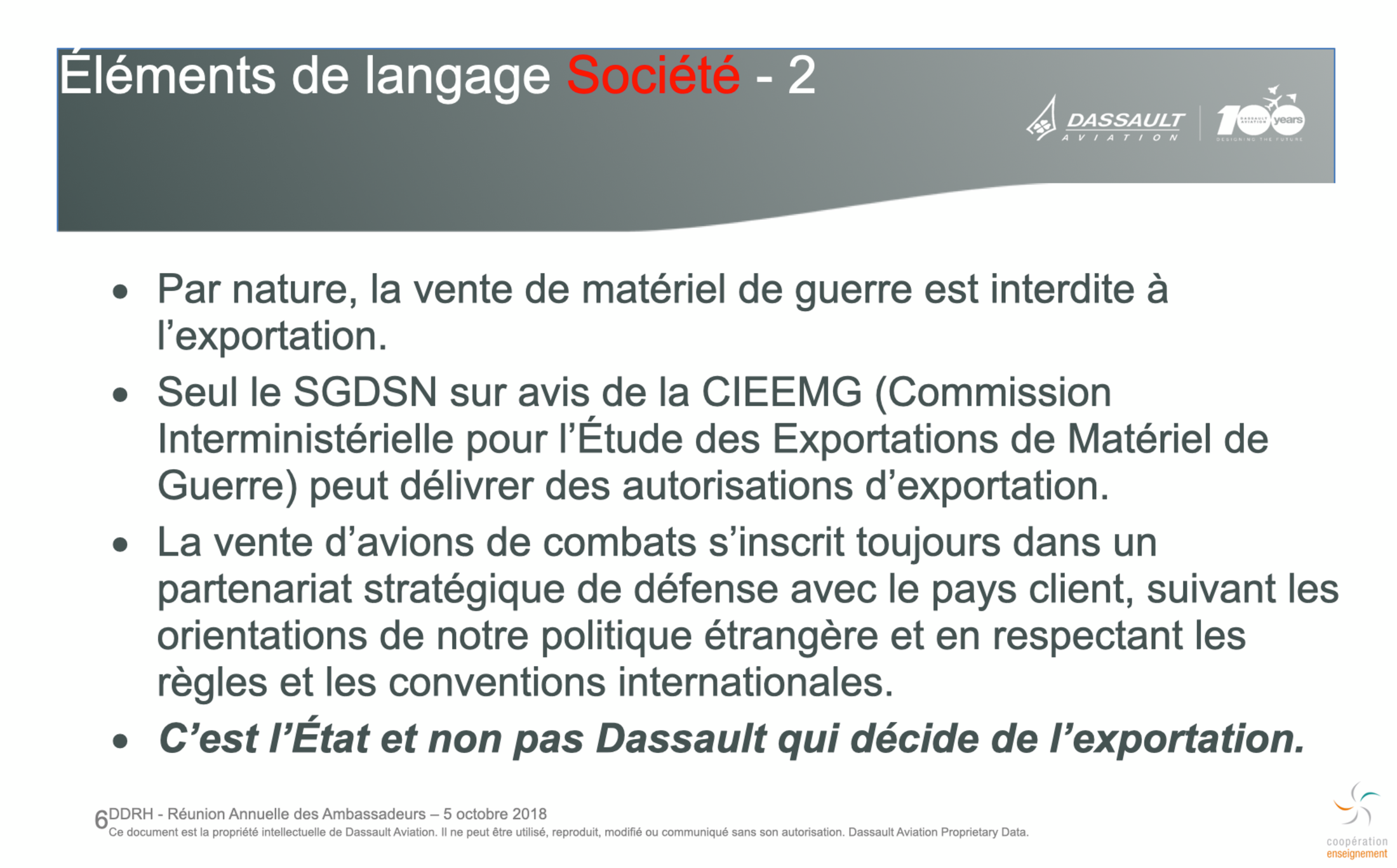

One of these is entitled “Elements of language on the export of military equipment”. Sent out to its “ambassador-teachers” on October 11th, and based on a similar document first produced in 2018, it was prepared by Nicolas Houël, the head of Dassault Aviation’s economic and strategic analysis centre. It contains a list of typical examples of sensitive questions they may be confronted with (see document below), which include: “What are the ethics of Dassault Aviation regarding weapons exports?”; “When it is said that you are arms dealers, what do you reply?”, and “Why do you sell arms to dictatorships/ to dubious countries?”

There is also section of possible questions that concern the “ambassador-teachers” on a more personal level: “Personally, does it not bother you to produce weapons?”, and “What effect does it have on you to sell arms to Qatar?”.

Under a list entitled “The principles”, advising on how to react, the document tells staff to “Never reply to the question directly”, “Don’t get into a debate”, and “Reply with assurance in a global manner”.

Enlargement : Illustration 2

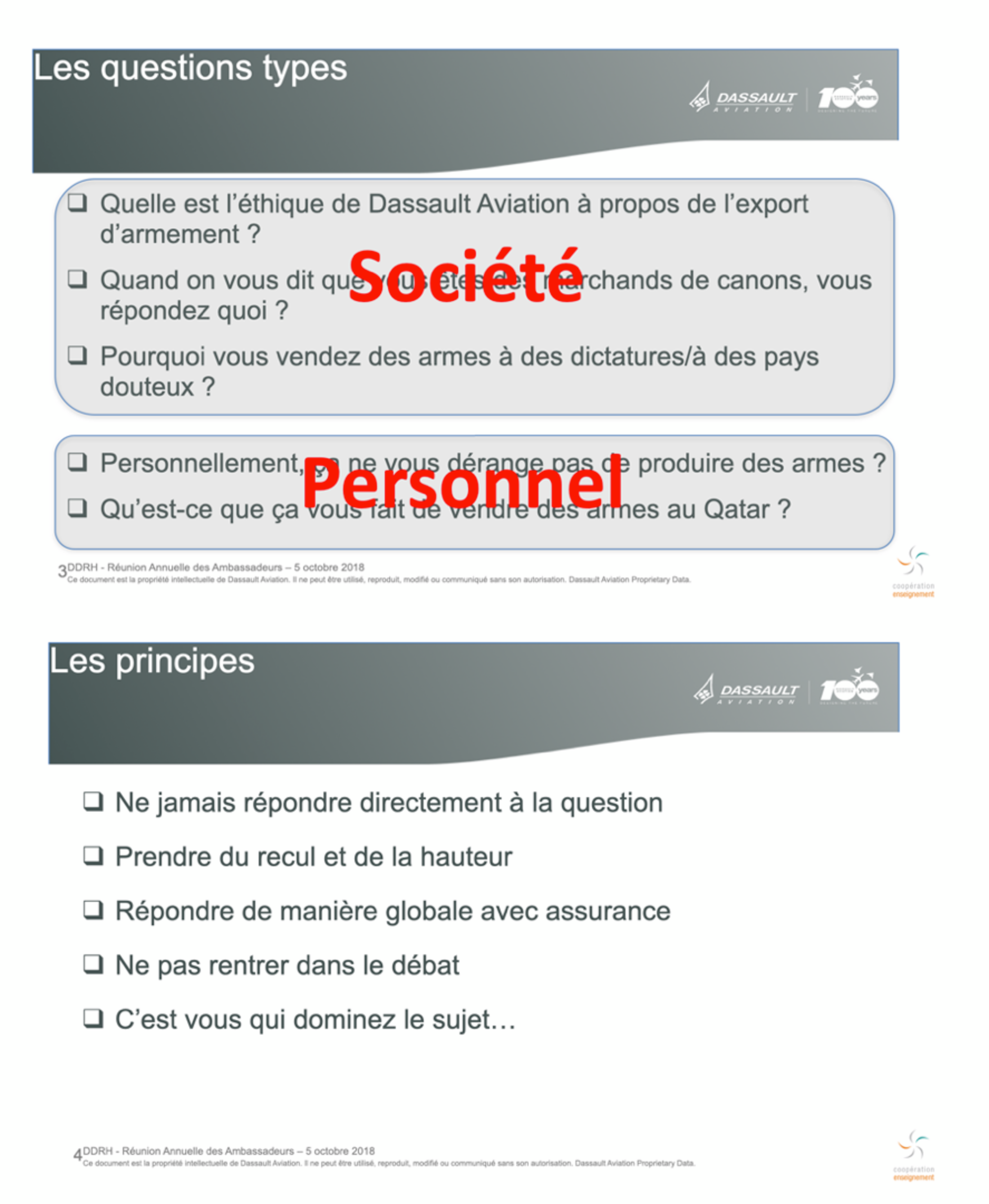

There then follows a more precise advisory note about “elements of language”, which essentially amounts to placing responsibility for weapons exports on the French state, which authorises arms exports via the secretive Inter-ministerial Commission for the Study of Exports of War Equipment (the Commission interministérielle pour l’étude des exportations de matériel de guerre), or CIEEMG. “The sale of combat aircraft is always made within the framework of a strategic defence partnership with the purchasing country, in line with the orientations of our [France’s] foreign policy and in the respect of international regulations and conventions,” it advises (see document below). It concludes with a mantra, set out in bold print: “It is the state and not Dassault which decides on exportation.”

That is a convenient evasion of responsibility, for Dassault Aviation, like any other company, is free to canvass the clients it wishes to, and it could in principle choose to refuse, on ethical grounds, to sell its Rafale fighter jets to countries like the United Arab Emirates or Qatar.

Enlargement : Illustration 3

To suggest that Dassault is submitted to the wishes and requirements of the French authorities might appear comical given the vast influence it wields within the state apparatus. In 2011, French financial weekly Challenges, in an article entitled “The truth about Dassault’s military lobbying”, for which one source was a former head of France’s Directorate General of Armaments, the weapons procurement administration, wrote of “the incredible strike force of the [Dassault] group on French defence policy”. Its influence has certainly not declined since, as illustrated by the fact that, in the intervening period since that report was published, the company has sold 285 Rafale jets in export deals.

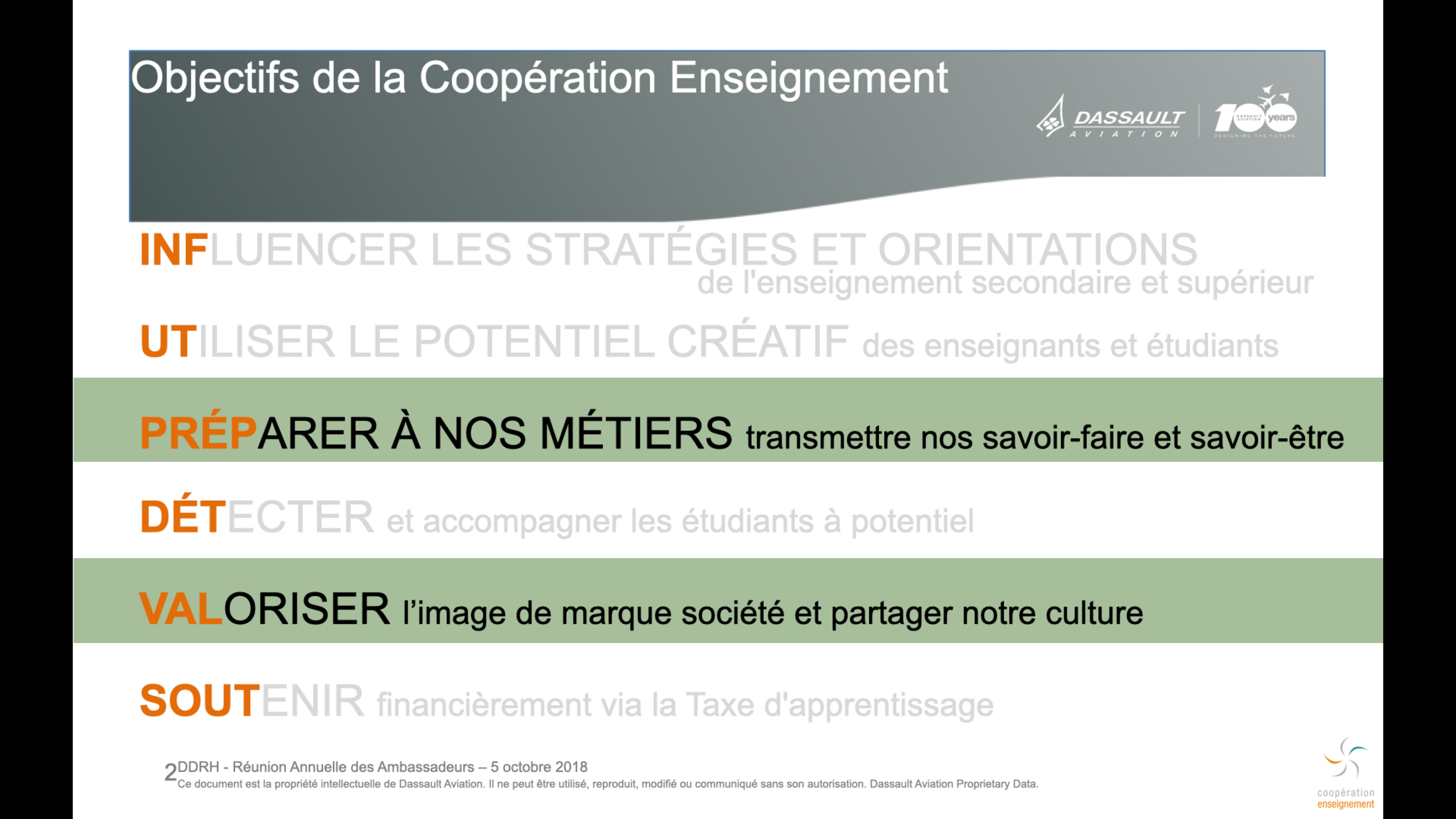

But as detailed in the internal company documents revealed here, Dassault Aviation also admits to be seeking “to influence the strategies and orientations of secondary and higher education” as set out by Nicolas Houël in a note entitled “Objectives of the Teaching Cooperation” (see document below).

Enlargement : Illustration 4

A former Dassault employee, whose name is withheld, told Mediapart how, in part, this influence is deployed. “The staff who are graduates of the grandes écoles were encouraged to join the boards of governors of these schools and to argue for the opening of courses that corresponded with the needs of Dassault Aviation,” he said.

Dassault Aviation did not respond to questions submitted to it by Mediapart, neither on that allegation nor to all other questions regarding the documents revealed here.

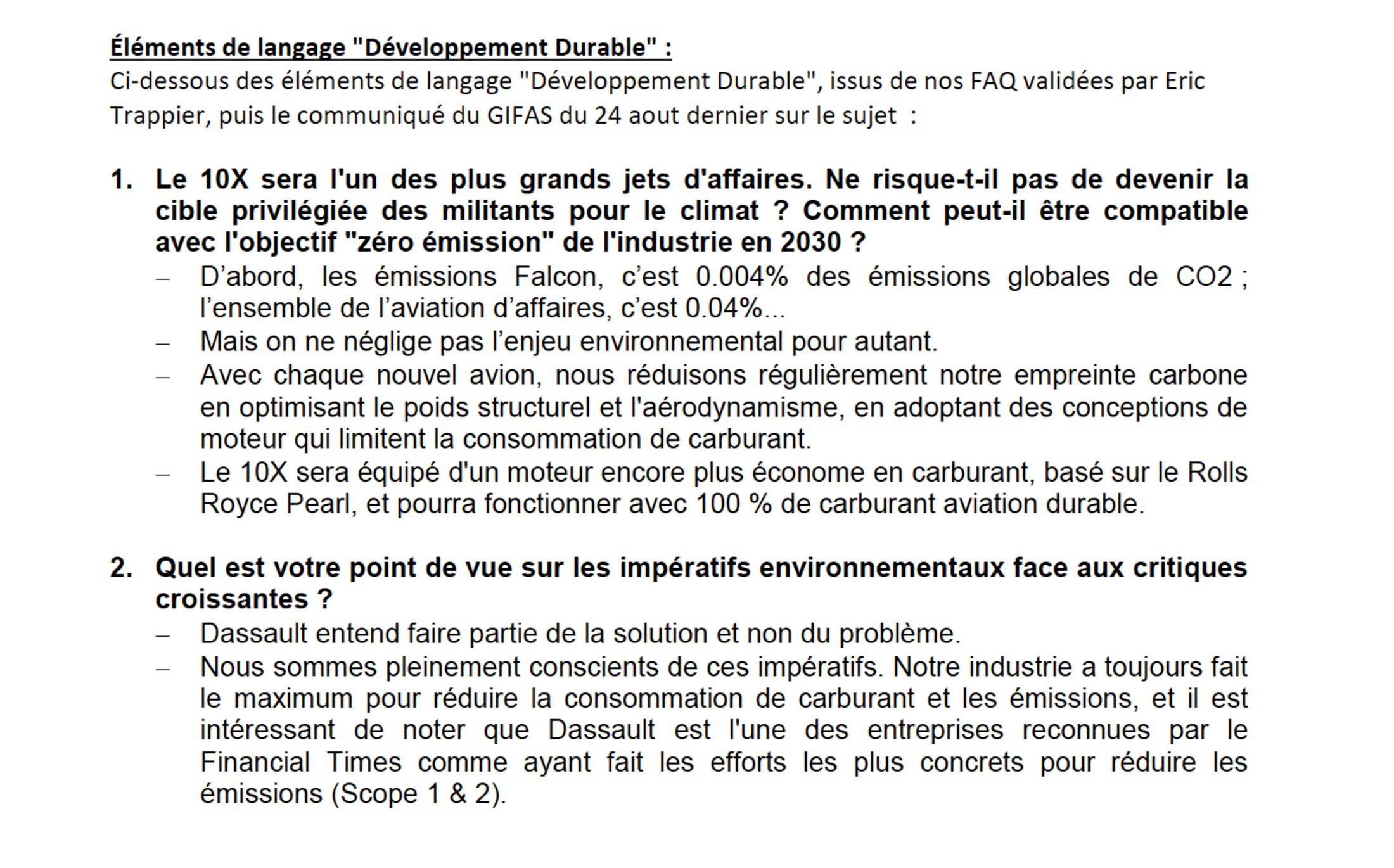

Another document obtained by Mediapart concerns “elements of language” regarding what it called “sustainable development”. The document noted that these were based upon “our FAQs validated by [Dassault Aviation CEO] Eric Trappier”. It was prepared with regard to the possible concerns of future recruits about the carbon emissions of the forthcoming Falcon 10X business jet, currently under development and due for launch in 2025, when it will be one of the largest aircraft in the category.

The document (see below) details that in response to the question of whether the new business jet becomes “the special target of climate militants”, it is to be noted, among other things, that “the whole of business aviation” represents “0.04% of global CO2 emissions”, and that “with each new plane, we regularly reduce our carbon footprint […] by adopting engine conceptions which limit fuel consumption.”

Enlargement : Illustration 5

While private jet flights are estimated to account for 2% of civil aviation emissions – which in turn represent a total of around 2% of global emissions – that figure should be put into perspective by the disproportionate carbon intensity of private jets. In a report published by Brussels based NGO Transport and Environment, and based on data from 2019, it is estimated that, per passenger, “private jets are on average 10 times more carbon intensive than commercial flights”, and fifty times more polluting than rail travel. Furthermore, according to the same report, the private owners of business jets are made up of a tiny proportion of the world population, and who on average dispose of a wealth of 1.3 billion euros.

Concerning Dassault’s argument that the engines of the group’s business jets are designed to consume ever-less amounts of fuel, a report by the Paris-based association The Shift Project, a think tank that researches the effects of fossil fuels on climate change, foresees that the technological advances in the domain will soon reach their limit.

Meanwhile, “aeronautic emissions continue to surge because of the explosion in traffic,” commented Pierre Leflaive, transport specialist with French association Réseau Action Climat, the French branch of the international Climate Action Network. “In sum, the [consumption] gains obtained by new engines are lost through the increasing number of planes in the air,” he said.

Except during the economic slowdown in 2020 brought about by the Covid-19 pandemic, the use of business jets has seen a boom over recent years, and in Europe alone, their CO2 emissions are estimated to have grown by a third between 2015 and 2019, according to NGO Transport and Environment. In its annual report published this year, Dassault Aviation noted a “clear resumption” in sales, “with 51 Falcons sold in 2021, against 15 in 2020”.

In its notes of advice to the “ambassador-teachers”, Dassault also argues that the upcoming Falcon 10X “will be able to operate with 100% of sustainable aviation fuel”, which is a biomass-derived fuel, essentially produced from plants or waste. For Pierre Leflaive, “to reserve our natural resources to de-carbonise jets is to consider that their use has priority over the biomass and land used for food, firewood, carbon sinks and so on”.

“Already, we won’t have enough bio-fuel for commercial aviation, so how can the exploitation of this biomass be justified for [private] jets, of which a large number of trips could be made by train?” he added.

According to the previously cited report by NGO Transport and Environment, around half of private jet flights in France in 2019 were for journeys of less than 500 kilometres. Among the most frequent connections by private jet are Paris-Nice, Paris-Geneva, and Paris-Lille, all of which can be made by high-speed train.

In its notes on “elements of language”, Dassault Aviation also highlights that “business jets have a double use, civilian and military, and fulfil numerous missions, notably air ambulance [services], the police [sic], border surveillance and surveillance of pollution”. But according to the latest data available from the European Business Aviation Association, a body which promotes the sector, fewer than 15% of business jet flights in Europe in 2021 were made for governmental, military, medical or humanitarian purposes.

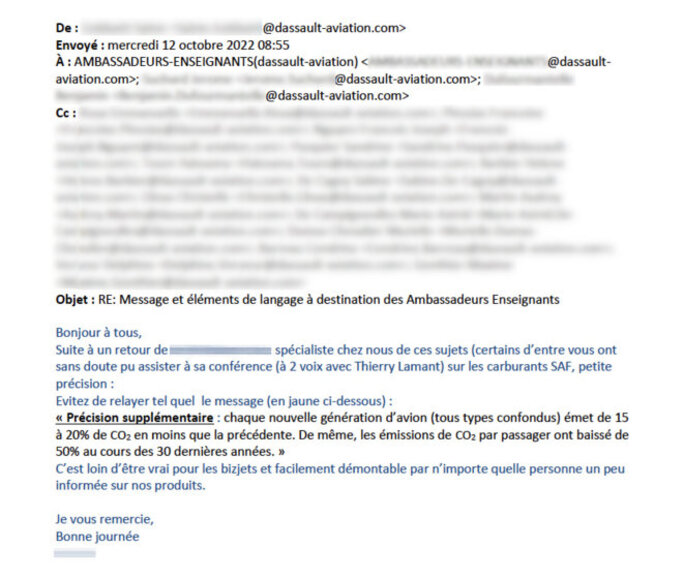

In Dassault’s advice to its “ambassador-teachers”, it also notes that: “Each new aircraft generation (of all types) emit between 15% and 20% less than the preceding one. Also, CO2 emissions per passenger have fallen by 50% over the past 30 years”.

But that was misleading, so much so in fact that on October 12th, Dassault sent out a correction to the “ambassador-teachers” (see below) warning them, on the advice of the company’s fuel consumption expert, not to use the argument. “It is far from being true concerning bizjets, and easily taken to bits by any person who is a little informed about our products,” the note concluded.

Enlargement : Illustration 6

For while succeeding generations of jets do emit less and less CO2, they are successively capable of travelling ever greater distances, and their weight has significantly increased. The future Falcon 10X is three times heavier than the Falcon 50 model that was launched in 1976, and it will be able to fly non-stop twice the distance that the Falcon 50 was capable of.

-------------------------

- The original French version of this report can be found here.

English version by Graham Tearse