Crépin Mbengue Nyimbilo, 30, says he still cannot bring himself to accept that his partner and their daughter died last month in excruciating conditions in the desert that lies between Tunisia and Libya. But he knows that it is their bodies which appear on a photo circulating on social media, posted by NGOs and others outraged at the plight of sub-Saharan migrants who reach North Africa, many of them hoping to continue their journey north to Europe.

For Crépin and his family, their hopes had been to start a better life in Tunisia. The photo, first posted on Facebook, shows the corpses of his 30-year-old Ivorian partner Matyla Dosso, face down on the sand, and their six-year-old daughter Marie, lying curled up alongside her.

The last time Crépin, from Cameroon, had seen them alive was on July 16th. That day Tunisian police had forced all three to walk across the sun-baked desert back towards Libya, where they had resided over several years.

“When I think that a simple bottle of water could have saved them,” said Crépin, speaking from Libya in a phone interview with Mediapart. “In seeing the photo, I had to recognise their deaths. But I still cannot manage to accept it. I wait for Matyla to call me on the phone, that she comes back to find me.”

The couple’s home was in the Libyan coastal town of Zuwarah, about 60 kilometres from the Tunisian border, where Matyla, who for convenience adopted the Arab-sounding name of Fatima (or “Fati”), was a house cleaner and Crépin, whose nickname is Pato, odd-jobbed as a painter-decorator on building sites. It was after five failed attempts to cross the Mediterranean Sea to Europe that they decided to try instead to settle in Tunisia in order, he said, to “guarantee a certain future” and “adequate” schooling for their daughter Marie.

Enlargement : Illustration 1

They had set off on July 13th, but after entering Tunisia by a clandestine route, they were soon arrested and detained by police, and subsequently taken back to the desert border zone where they were abandoned and ordered to march back into Libya.

Parched and exhausted from the previous three days of walking, they had been given no food or water for their trek across the desert, like hundreds of other sub-Saharans similarly expelled by the Tunisian authorities since the beginning of July.

As they advanced across the s and towards Libya that Sunday three weeks ago, Crépin collapsed to the ground. “I no longer had the strength, I was hardly breathing,” he told Mediapart. “To save them, I told them to go and leave me there.”

High tensions in Tunisia

The family had embarked upon their journey unaware of the current climate of violence and repression targeting black migrants in Tunisia. Tensions have notably spilled over since the increasingly hardline Tunisian president Kaïs Saïed in February denounced what he called an “unusual” wave of immigration that had led to “unacceptable violence and crime”. Saïed spoke of a “criminal plan that had been in place for decades to change Tunisia's demographic make-up” which he said was aimed at making Tunisia “entirely African” and to end its attachment to the community of “Arab and Islamic countries”.

NGOs have documented the subsequent deportations of sub-Saharans, estimated to involve around 1,000 people, and there have been violent clashes between Tunisians and sub-Saharans in the eastern coastal region, which were further fuelled by the fatal stabbing in early July of a Tunisian man in the port city of Sfax.

After being turned away during their first attempt to enter Tunisia from Libya, Crépin, Matyla and their daughter Marie finally managed to cross the border during the night of July 14th-15th. “We then walked to the town of Ben Gardane,” he told Mediapart.

Crépin said that that when they arrived close to a mosque in Ben Gardane, a coastal town near the border with Libya, they asked a local woman for help in finding water but, shortly after, a police vehicle arrived, when they were ordered to climb aboard. Matyla, who was suffering from menstrual cramps, asked to be taken to a hospital. “Instead of that they took us to a police station close to the desert,” recounted Crépin. “They hit all the men, took my phone and our money.” The three spent the night sleeping rough on the ground, watched over by guard dogs.

On the morning of July 16th, they saw a group of other detained migrants being ordered onto a police vehicle. “Our turn came next,” said Crépin. “That was when they abandoned us in the desert.”

They began the march back to Libya, physically worn out and suffering under the heat of the sun. He said they had by then not had any water for 24 hours. “Matyla was so thirsty that she asked the little one to urinate in her mouth, but Marie couldn’t because she was completely dehydrated.”

Crépin recalled the moment when he collapsed: “I couldn’t carry on anymore, and I couldn’t force them to stay with me. I told them, ‘God willing, we’ll meet up again in Libya’.” The idea was for Matyla and Marie to catch up with a group of sub-Saharans, similarly abandoned to their fate in the desert, who they had spotted in the far distance. His wife’s last known sign of life was when she got in touch by phone, via WhatsApp, with a former neighbour of the couple. That was at 5.50am on Monday July 17th.

Enlargement : Illustration 2

The positions in which the bodies of Matyla and Marie were found on the photo, with Marie curled up against her mother, leads Crépin to believe that they had first gone to sleep, and that his wife lost consciousness before his daughter. “They must have been exhausted, and must have laid down on the sand,” he said. “Marie must have placed her hand on her mother after seeing that she was no longer reacting.”

Discovering the photo, so many questions remained unanswered for Crépin. What became of their bodies? Were they buried, and where and in what conditions? Might he one day be able to find and visit their tombs? For him, they died in despair after failing to join the group of migrants they had seen in the distance. They never came across border guards, and never found water.

Crépin, who had lost consciousness after they left him, came around at nightfall on July 16th. He had dreamt, or hallucinated, of finding five litres of water and drinking it in one go. “I don’t know why nor how, but it gave me the strength to get up.” Then, in the darkness, he saw two shadows approaching.

They were two Sudanese migrants, who had also been expelled into the desert by the Tunisians. They gave him a bottle of water, and the three men continued their route together to Libya, which they reached in the early hours of July 17th. They crossed into the country at the time of morning prayers, when the border guards were less vigilant, and eventually found a farmer who agreed to drop them off in Zouara, where Crépin, Matyla and Marie had lived until then.

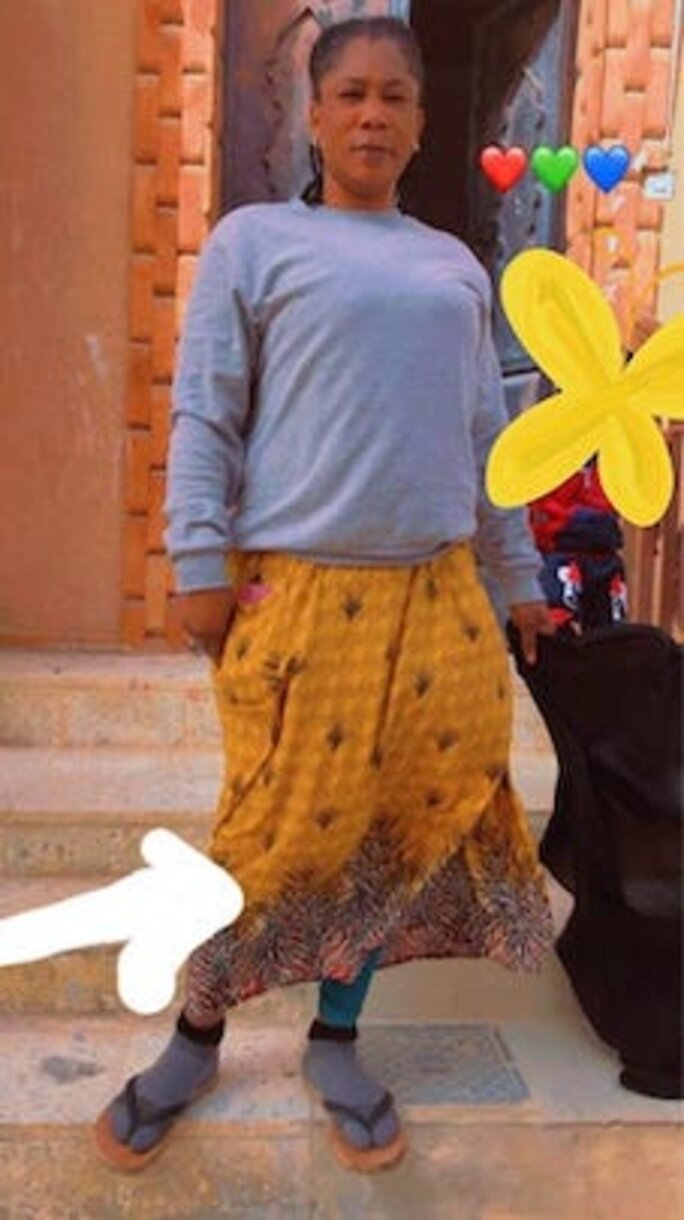

“I went to our home, certain that I would find them there,” Crépin said. But without any news of them, he then thought that they may have been arrested and detained. It was two days later when a friend of the family asked him to come round urgently. “He had seen the photo and thought he recognised Marie. He asked me to sit down and to be strong for what I was about to see. I immediately recognised Matyla’s yellow dress and my little Marie,” said Crépin, his voice full of emotion, adding that the picture will “haunt” him for the rest of his life. “My body is intact, but my mind is extinguished,” he said.

He had many pictures of the two, which were lost to him after the Tunisian police confiscated his phone. But searching through his Google account he found a picture of Matyla in happier times, in which she is seen wearing her yellow dress. It was that which allowed the NGO Refugees in Libya, which offers active support to refugees and migrants across North Africa, to formally identify her and Marie as the victims in the desert. The NGO has since found a safer home in Libya for Crépin, who said he was threatened by phone after he first gave his account of the tragic events to the news agency Associated Press (AP), published in a report on July 29th.

From exile, to dreams, to tragedy

Crépin first met Matyla after arriving in Libya in 2016, which he said his migratory route from Cameroon took him to “a bit by chance”. He is from Cameroon’s south-west region, which armed separatists have laid claim to. “I had left [the city of] Buea in Cameroon when the region was targeted by the secessionists and when they wanted me to enrol with them. They killed my elder sister because I refused,” he said.

Arriving in Libya, Crépin ended up in the so-called “campo” clandestine centre, close to Tripoli, where people smugglers kept migrants while they waited to cross the Mediterranean. Surrounded by mostly anglophone migrants, he came across Matyla, a fellow francophone, who he said had fled from a “complicated life” in her native Ivory Coast. They soon became a couple. “We spent a few weeks there, and we conceived Marie there,” recounted Crépin.

When it was their turn to attempt to cross the Mediterranean, they were caught by Libyan coast guards and separately imprisoned in the country’s notorious detention centres of Bani Waled, south-east of Tripoli, and in Sabratha, about 200 kilometres distant, on the north-west coast. But he found trace of her on Facebook, when he also discovered that she was pregnant. They were, he said, “happy” to start a family, and Matyla gave birth to Marie in March 2017.

The lives of blacks don’t count in the Maghreb

After their release from detention, Matyla (who dreamt in vain of opening a restaurant which she would call L’Abidjanaise, a reference to the largest city in her native Ivory Coast) found work as a domestic cleaner for Libyan employers, while Crépin found intermittent jobs as a painter on construction sites. Meanwhile, Marie was not entitled to schooling.

“We never managed to cross [the Mediterranean],” Crépin told Mediapart. “We chose to go to Tunisia thinking that it would be better than here.” But, he said, in the Maghreb region of North Africa “the lives of blacks don’t count”, adding that he hoped that their tragic story could also “bring that reality to light”. He said the deaths of Matyla and Marie were “gratuitous”, that they lost their lives “for nothing”.

In the AP report dated July 29th, the news agency cited Libyan major Shawky al-Masry, spokesperson for the country’s border guard service, as saying it was officers from its al-Assa station, close to the Tunisian border, who found the bodies that feature in the photo. He gave the agency no further details, including where their corpses were taken.

But when Mediapart spoke to Crépin, he said a woman had called him on July 30th to inform him that Matyla and Marie were buried by Libyan security forces in the town of Ajmail, about eight kilometres south of Zuwara. “A commander then contacted me to ask if I wanted to visit them,” said Crépin. “He was due to propose a date for me, but I’ve had no more news.”

-------------------------

- The original French version of this report can be found here.

English version by Graham Tearse