The beaches of the Kerkennah Islands in Tunisia, which lie a short distance off the eastern port city of Sfax, regularly bear witness, through the discoveries of washed-up corpses and debris, to the tragedies that befall migrants attempting to cross the Mediterranean Sea in frail, often overcrowded boats.

On December 24th 2022, Boulbeba Bougacha went to spend lunchtime with a few others at the Sidi Founkhal beach on Chergui island, the largest of the Kerkennah archipelago, arriving at around 1pm. Shortly after, the 20-year-old came across the body of an infant girl, dressed in a pink jacket and blue trousers, lying face down on the pebbles of the beach, just a few metres from the sea.

Enlargement : Illustration 1

“We found her there, lying on her stomach,” he told Mediapart, which travelled to Tunisia to meet him. “We called the authorities, who came to collect her. It was a shock. We know that lots of people die at sea, but one is never prepared for seeing such a thing.”

That same day, the corpses of at least three other people, all adults from Sub-Saharan Africa, were also washed ashore on the islands.

While Bougacha was interviewed two days later by a local radio station, Diwan FM, both the discovery of the infant and the photo that Bougacha took of her at the beach where she was found were hardly mentioned in Tunisia or elsewhere, aside from a few, rare posts on social media.

Yet the photo is strikingly similar to that of the body of two-year-old Alan Kurdi, which was found lying face down on a beach in Turkey in September 2015. He had drowned, along with his mother and brother, all Syrian Kurds, during their attempt to reach Europe by boat. The shocking photo of the corpse of the small boy made headlines around the world, prompting widespread emotion and attention to the plight of those who seek exile from hardships in their native countries.

Many among the Kerkennah archipelago’s population of around 15,000 are aware of the little girl’s body found at the beach of Sidi Founkhal. But since several years now, the initial shock caused by the first discoveries of the bodies of drowned migrants has left place to a form of resilience in face of such tragedies. “We see corpses almost every day,” said Nasser (not his real name, which he asked to be withheld), who makes a living from fishing, the key industry of the islands.

When Mediapart met him in Remla, the capital of the archipelago, situated on Chergui island, he appeared relieved to be able to talk about his experiences. He said that in the spring of last year he also found the body of an infant, who he thought could have been two-years-old at most. “The last time, I saw four or five dead people in one go,” he said. “When we call the National Guard, they ask us if they [the corpses] are white or black. If it’s blacks, they don’t come out.” The National Guard is a policing force which acts under the authority of the interior ministry.

Since the early 2000s, the Kerkennah Islands have become a departure point for those attempting clandestine crossings to Europe, and notably the Italian island of Lampedusa, about 180 kilometres north-west of the archipelago. Many are Tunisian, but since about ten years ago increasing numbers of people from Sub-Saharan Africa have travelled to Tunisia, as well as neighbouring Maghreb countries, both to seek work and to make the crossing.

“Because of its location, Sfax has attracted many Sub-Saharans,” said Hassan Boubakri, a lecturer in geography and migration studies with the universities of Sousse and Sfax. “Firstly, because it is the second largest city in Tunisia and there is a strong need for workers, and then also because it is close to Kerkennah, where [clandestine] crossing networks already existed.”

“The authorities now monitor the islands a lot,” added Boubakri. “Blacks can no longer reach Kerkennah and Tunisians, to get there, must provide justification that they are going for work or to visit close relations.”

Those local fishermen who agreed to talk to Mediapart all confirmed the crackdown, but they said that clandestine crossings launched from the archipelago nevertheless continue. Others attempt the crossing from Sfax, which is a longer and more dangerous route.

Speaking to Mediapart in Remla on the Kerkennah archipelago, Nasser the fisherman warned that, “A day like this, with a northerly wind that’s rather strong, is going to bring us several corpses to the island.” He spoke of the trauma at seeing the victims’ disfigured faces, and bodies eaten away by fish or the migratory birds that are common on the islands. “The last time, I was so affected by what I had seen that on the way back home I had to stop at the roadside to recover my mind,” he recalled.

Enlargement : Illustration 2

Skeletons are also discovered, which fishermen say are mostly found on the island of Roumedia, situated in the far north-east of the archipelago, where, according to one of Nasser’s friends, also a fisherman, human remains have been left there since Eyd al-Fitre last April, the Muslim holiday that marks the end of the Ramadan fasting period. “We reported it but no-one came to collect it,” said the man, who asked not to be named.

Another fisherman present recounted how he had not reported a body he came across when out at sea one day. “If I had mentioned it to the National Guard, they would have then asked me to accompany them to the corpse,” he said by way of explanation. “It was too far out and there was every chance that I wouldn’t have been able to find it again.”

Fishermen on the southernmost island of the archipelago, Gharbi, speak of regularly finding bodies in their nets. Another on the island, Ali (not his real name), said he even found the body of a man blocked in a “charfia”, a traditional fishing technique consisting of a triangular barrier made of palm fronds which block the paths of fish and channel them into capture chambers. “I called the national guard at 11 am,” he recalled. “I waited until 3pm but no-one came to collect it. The next day I found the body at the same spot.” He said the National Guard told him the delay was due to a lack of resources.

For Hassan Boubakri, who aside from his university teaching is also chairman of an NGO called the Tunis Centre for Migration and Asylum (CeTuMA), the large numbers of drownings of migrants attempting to cross the Mediterranean has led to the phenomena being regarded as commonplace, an everyday feature of local life. “There are the media who regularly report on the death tolls, the fishermen who are no longer surprised to pull corpses out of their nets, the people who live beside the sea who suffer from witnessing all that,” he said.

“All the actors involved, like the National Guard, the judicial apparatus, forensic medicine, or the Red Crescent, have become, even without being aware, party to this ‘ordinariness’,” Boubakri added. “Everyone agrees on saying that the Mediterranean has become a cemetery, whereas that should arouse compassion. But we have moved from compassion to indifference, with very few perspectives for solutions that can protect those people under threat.”

Some NGOs provide practical help to those who find themselves in difficulty at sea, like Alarm Phone, whose mission is to ensure distress calls are acted upon. But in the cases where people lose their lives, other organisations are actively involved in documenting the tragedies and identifying the victims. That is the case of the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) and which works in co-operation with the Tunisian Red Crescent in the search for, and identification of, the remains of those lost at sea.

While the identification of those who have drowned is primarily the responsibility of the Tunisian authorities, the ICRC acts as a backup to the process, by working on missing persons reports, which are most often submitted by those close to the person who has disappeared. The ICRC will document details that may allow to trace a recovered body, such as clothing or distinctive physical features.

Enlargement : Illustration 3

The process of identification of bodies is less arduous when the victims are Tunisian; many families are mobilised to find trace of their missing, and the local authorities can consult finger print records. But it is far more difficult in the cases of non-Tunisians, whose families living in distant countries may not know what migratory route their relatives embarked upon. In such cases, the ICRC relies information from acquaintances of the missing person, or those they may have come across during their travels.

“Some are afraid to report a disappearance to NGOs because they don’t see the difference between them and the authorities – they don’t want any problems,” said Yaha (last name withheld), an Ivorian who runs a business in Sfax where she has lived for the past six years. She spends much of her free time helping those seeking news of someone close to them who has disappeared, notably by accompanying them to the Red Crescent.

When Mediapart met with Yaha in Sfax, she was helping two young men from Ivory Coast who were seeking news of a group of seven people. “There are five adults and two children, aged two and eight months,” explained one of them, looking for photos of his friends on his mobile phone. “We know they died at sea. Now, we want to know where their bodies have been found.” Might the infant found on the beach in the Kerkennah Islands have been among them? They had no idea. “People don’t warn others when they leave,” said the other young man.

The two of them were due to go to the National Guard offices in Sfax two days later, where they would be able to consult the files of photos of the bodies found. They would be accompanied by someone from the Red Crescent, both to ease their fears of the authorities and to offer them emotional support.

Until now, no-one, neither in Tunisia nor in Italy, has asked the ICRC for information about the little girl found at the beach of Sidi Founkhal. Those among local associations providing support for migrants believe her parents undoubtedly drowned with her. “We think there were no survivors from that boat,” said one association representative, who asked for his name to be withheld. “She was found at a time when there were many sinkings. All we know is that she has black skin, like the adults found the same day.” Mediapart was told that her body was kept for a while at the morgue of the Sfax hospital, and later buried.

“When there is a sinking, it’s the National Guard that must mount a rescue operation,” explained a woman activist with a local human rights group, and whose name is also withheld. “If there are people who died, they bring them back to shore, where the technical and forensic unit takes photos and DNA samples. [The corpses] are then taken to the morgue, [and stay] until someone asks for them, or until there’s a burial order from the municipality for those who have not been identified.”

The problem, however, is that the Sfax hospital mortuary has a capacity for just 40 corpses. There have been incidences when, for lack of space, corpses were left on stretchers in the hospital corridors.

Representatives of the hospital declined Mediapart’s request for comment. But in a service report that Mediapart consulted, the hospital noted a “clear increase” in drownings at sea over recent years. It also detailed that over the first six months of 2022, the majority of known victims of sinkings off the coast of Sfax were black, and that infants and children represented 5% of the bodies recovered. For most of the drowned, no identity papers were found on their person.

“Everyone is overwhelmed by the migrations,” said Wajdi Mohamed Aydi, deputy mayor of Sfax and responsible for the city’s policies towards migrants, and who points the finger at a lack of proper governance on the issue at a national level. “There are attempted crossings and accidents every week, even every day. We look after burying people who are unidentified, while trying to best respect their dignity.” For those with no known name, a number is placed on their gravestone.

The deputy mayor also spoke of the recent phenomenon of attempted crossings of the Mediterranean in metal boats, which a number of sources told Mediapart were sometimes built by the migrants themselves with the aid of Tunisian smuggling networks. The use of metal boats was also confirmed by the rights activist cited above. “These new metal small crafts are a catastrophe,” she said. “They try to build as many as they can by the hour, and don’t solder them properly. People have little chance of surviving in the case of a sinking because the boats sink faster, and they remain trapped inside.”

Lying six kilometres south of Sfax is the Ben Saïda quarter, where a large community of people from Sub-Saharan Africa live. There, Mediapart met with a 16-year-old boy called Junior, who comes from Guinea-Conakry. He lives in a half-built house alongside around 70 other youths. Some are also Guinean, others are from Cameroon, Ivory Coast, Mali and Senegal. All have tried and failed to make the crossing to Europe, and are waiting for the opportunity to attempt the journey again.

Enlargement : Illustration 4

In the darkness inside the house, mattresses and blankets were spread over the floor. Dozens of the young inhabitants jostled to greet us, curious at our presence. The majority appeared to be adolescents, but their faces showed the fatigue of their lives in exile. “We were intercepted by the National Guard two weeks ago,” said Junior, recounting an attempted crossing. “They deliberately put us in difficulty. My brother Mohamed fell into the water and drowned.” He showed us a video, posted on TikTok, which purports to show a National Guard launch rushing at a small migrant boat that refused to stop. He also showed us injuries to his feet, which he said were caused during the interception of the boat he was in and which have not been attended to.

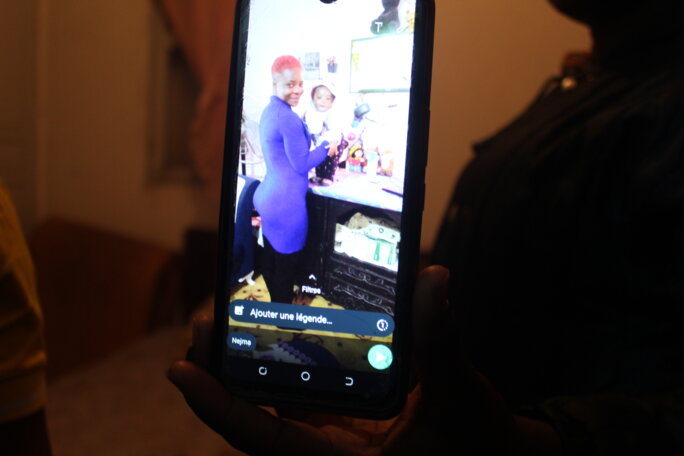

A few women also live in the house. They told us they were worried about a couple and their baby who had gone missing three weeks earlier. “We know they wanted to cross,” one of them said. “We have no more news, we think they died at sea.” She showed us a photo on her mobile phone, showing the missing woman smiling with her baby.

Enlargement : Illustration 5

But despite that disappearance, the women also want to attempt a crossing. “But I’m very afraid of water, I don’t know how to swim,” said one, who recounted she had fled her country to escape domestic violence.

Junior said he had not been able to summon the courage to contact the Red Crescent about his brother. “I imagine my brother has been buried,” he said. “I don’t try to find out because it’s too heavy for me, it makes me feel sick just to think about it.” The teenagers around him appear to be resigned to the dangers ahead. “We can’t stay in our country, and we can’t stay here,” said one of them.

They complain of racism and mistreatment. “Some policemen stole my mobile [phone] the other day,” said another. “At the police station, they didn’t want to take down my complaint. In the grocery stores they don’t want to sell us rice because there’s a shortage and we don’t have priority.”

The representative of the local association that provides aid to migrants, cited further above and who did not want to be named, confirmed there was a climate of harassment. “Their living conditions have hardened,” he added. “Since a little while, a blockage has been put in place at the post office so that they can neither send nor withdraw money.” He added that he had personally witnessed over recent months the “arbitrary arrests” of individuals who had no legal residency papers.

“That’s also what pushes people to put to sea,” commented Yaha. “If they remain here without papers, it’s like an open-air prison. If they want to return home, they have to pay a fine.” Some nationals from Sub-Saharan countries, like Ivory Coast, are allowed visa-free stays in Tunisia of a maximum three months, but a fine is imposed on those foreigners who stay beyond three months without legal work or residency permits. The fine increases in increments according to the length of time they have exceeded the three months, and can reach a maximum of 3,000 Tunisian dinars (about 900 euros).

“With that money, some prefer to leave for Europe, where they could offer a better future for their children,” said Yaha.

-------------------------

- The original French version of this report can be found here.

English version by Graham Tearse

-------------------------

If you have information of public interest you would like to pass on to Mediapart for investigation you can contact us at this email address: enquete@mediapart.fr. If you wish to send us documents for our scrutiny via our highly secure platform SecureDrop please go to this page.

-------------------------