It was on March 26th 2019 in New Delhi when officers from India’s Enforcement Directorate, a government agency tasked with fighting economic crime and money laundering, arrested Sushen Gupta, an influential intermediary in arms deals. After spending two months in preventive detention, he was charged with “money laundering” and released on bail.

The charge related to a vast corruption scandal which first erupted in 2013, dubbed “Choppergate”, which centred on a 550-million-euro contract for the sale to India of helicopters manufactured by the Italian-British firm AgustaWestland. While several individuals cited in the case were eventually cleared of wrongdoing by the Italian justice system, in India the investigations are continuing.

Gupta and other intermediaries were paid, using inflated invoices for what were termed as “software consultancy” contracts, more than 50 million euros in commissions by AgustaWestland through offshore companies. According to the criminal complaint filed against Gupta, who denies wrongdoing, the Enforcement Directorate (ED) suspects that part of the money was paid as bribes “to politicians, bureaucrats and government functionaries”.

In their investigations into the routes of the secret funds, the ED discovered that Gupta also “received kickbacks” in order to influence the result of “other defence deals”. The money was found to have transited through the same shell companies and the same types of “software consultancy” contracts used in the helicopter deal.

Enlargement : Illustration 1

According to information gained by Mediapart, one of those “other defence deals”, which is not identified in the charge sheet, is the inter-governmental agreement signed in 2016 for the 7.8-billion-euro sale by France to India of 36 Rafale fighter aircraft, built by Dassault Aviation.

In the official charge sheet dated May 20th 2019 against Sushen Gupta, the ED wrote that “since kickbacks from the other defence deals are not a subject matter of the present investigation” about the AgustaWestland scandal, “separate investigations would be undertaken” regarding the other deals.

Already in 2019, Indian investigative news website Cobrapost, and followed later by Indian daily The Economic Times, revealed the contents of documents demonstrating links between Dassault, Sushen Gupta and the sale of the Rafale fighter jets.

Yet two years later, there remained no visible evidence that the ED had opened an investigation focused on the Rafale deal. Contacted by Mediapart, the agency did not comment on whether such a probe had been launched.

Enlargement : Illustration 2

Which raises the question as to whether the suspicions of corruption surrounding the Rafale contract had been buried by the investigative authorities in India, as was the case in France (see more on this in the first and second part of Mediapart’s “Rafale Papers” investigations here and here ). What is certain is that the affair has become highly sensitive given that serious questions are raised about the involvement in the deal of a close acquaintance of ultra-nationalist Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi (see more here)

Meanwhile, thanks to witness statements, the results of searches of premises and international judicial assistance, the ED has gathered a mass of evidence concerning Sushen Gupta, including computer files, email correspondence, banking details, agendas and other handwritten documents.

Mediapart has obtained a number of confidential documents from the ED’s case file, which shed new light on the behind-the-scenes events of the Rafale deal.

The first two reports in this three-part investigation have stirred public opinion in India over recent days, and Mediapart’s revelations here are likely to heighten the controversy.

According to documents obtained by Mediapart, Dassault and its French industrial partner Thales – a defence electronics firm in which Dassault and the French state are the major shareholders – paid Sushen Gupta several million euros in secret commissions to offshore accounts and shell companies, using inflated invoices for software consulting. These payments were on top of a questionable contract with Dassault for making replica models of Rafale jets, worth 1 million euros, which was revealed in the first of this series of reports.

As middleman for Dassault and Thales, Sushen Gupta, amid the discussions over the Rafale deal in 2015, obtained confidential documents from India’s defence ministry relating to the activities of the negotiating team. The Enforcement Directorate, in its official charge sheet against him, wrote that Gupta had gained “sensitive data which should have only been in possession of the Ministry of Defence”.

It is not clear how Sushen Gupta, who did not respond to Mediapart’s attempts to interview him, managed to obtain the information. Three years earlier, in a note from his archives dated September 7th 2012, and which appeared to be addressed to Dassault, he warned: “Cannot stop now too late for me, I owe people money and commitments. […] People sitting in office asking for money. […] Those people will, if we don’t pay, put us in jail and […] then we are really finished, deal scrapped.”

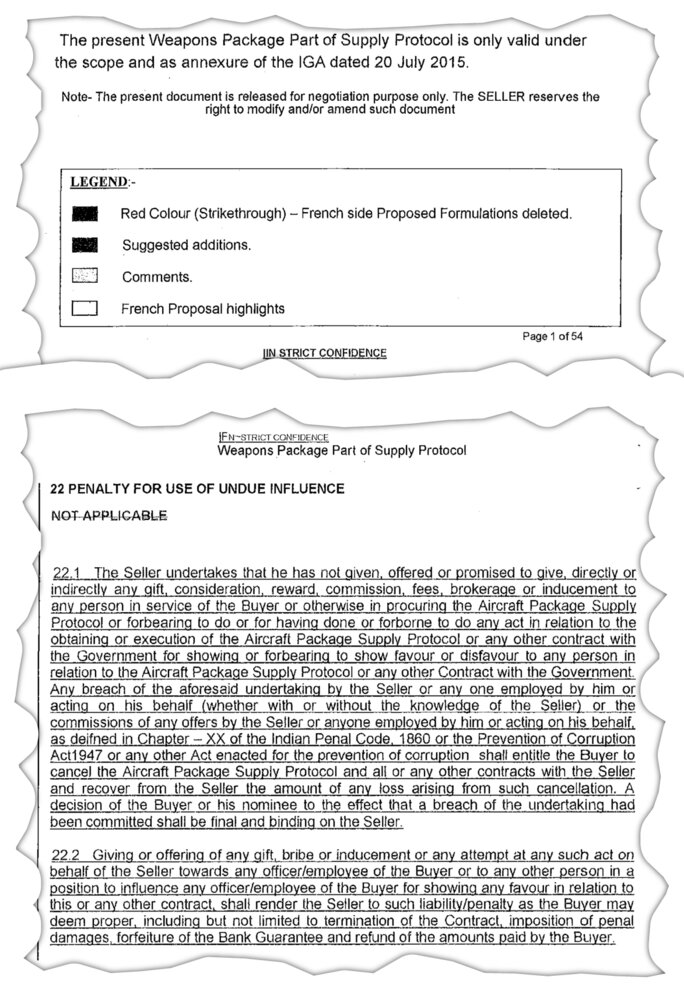

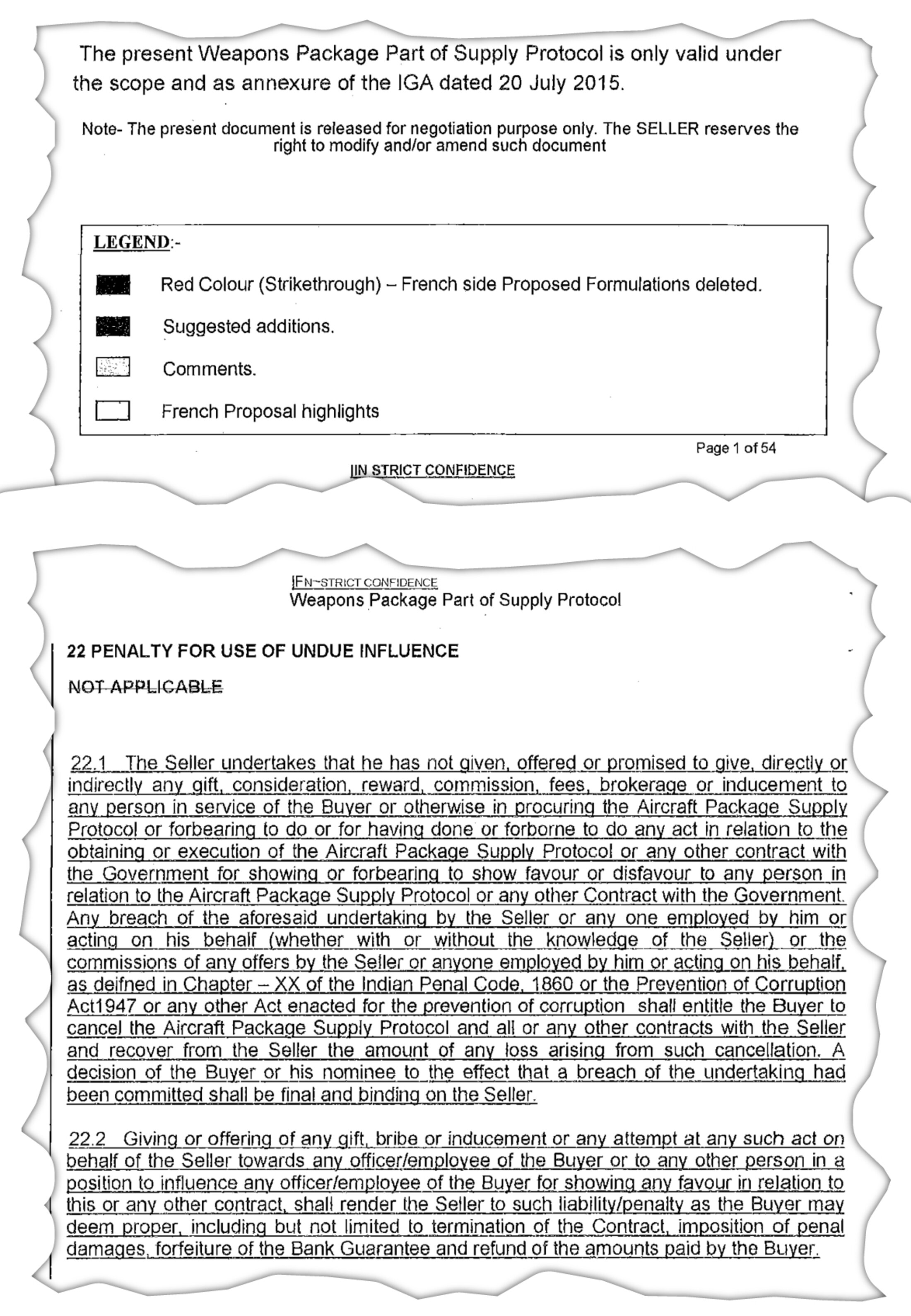

- How France removed anti-corruption clauses in the contract

The evidence found by the Indian investigators may help to understand why Dassault and France-based European missile manufacturer MBDA, which was also a party to the Rafale deal, worked hard to remove anti-corruption clauses in the inter-governmental agreement for the jets, which was negotiated and signed by Jean-Yves Le Drian, who was then France’s defence minister during the presidency of François Hollande, and who is now foreign affairs minister under President Emmanuel Macron.

Enlargement : Illustration 3

Those anti-corruption clauses could have had costly consequences for the industrialists, for they allow for India to rip up the contract and/or to demand compensation not only if acts of corruption are discovered, but also if the seller paid an agent in order to “intercede, facilitate or in any way to recommend [the seller] to the Government of India or any of its functionaries”.

India’s defence ministry was required, under the terms of the country’s “Defence procurement procedure” to include the clauses in question – “penalty for use of undue influence” and “agents/agency commission” – into the contract. But the French “Team Rafale” wanted them excluded.

In July 2015, in an annexe to the contract concerning the weaponry of the jets, supplied by MBDA, the French side wrote into the text that the two anti-corruption clauses were “Not Applicable”. But the Indians deleted this and reintroduced the anti-corruption clauses (see extracts from the documents immediately below).

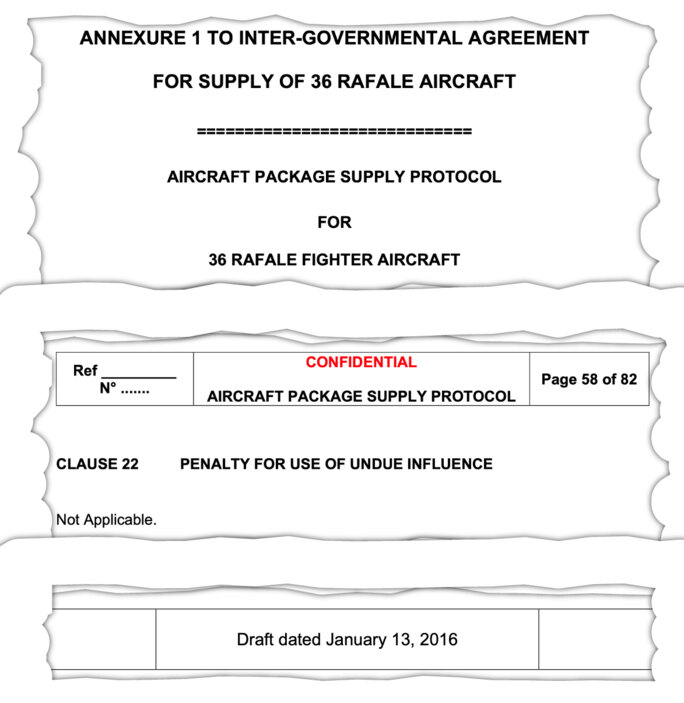

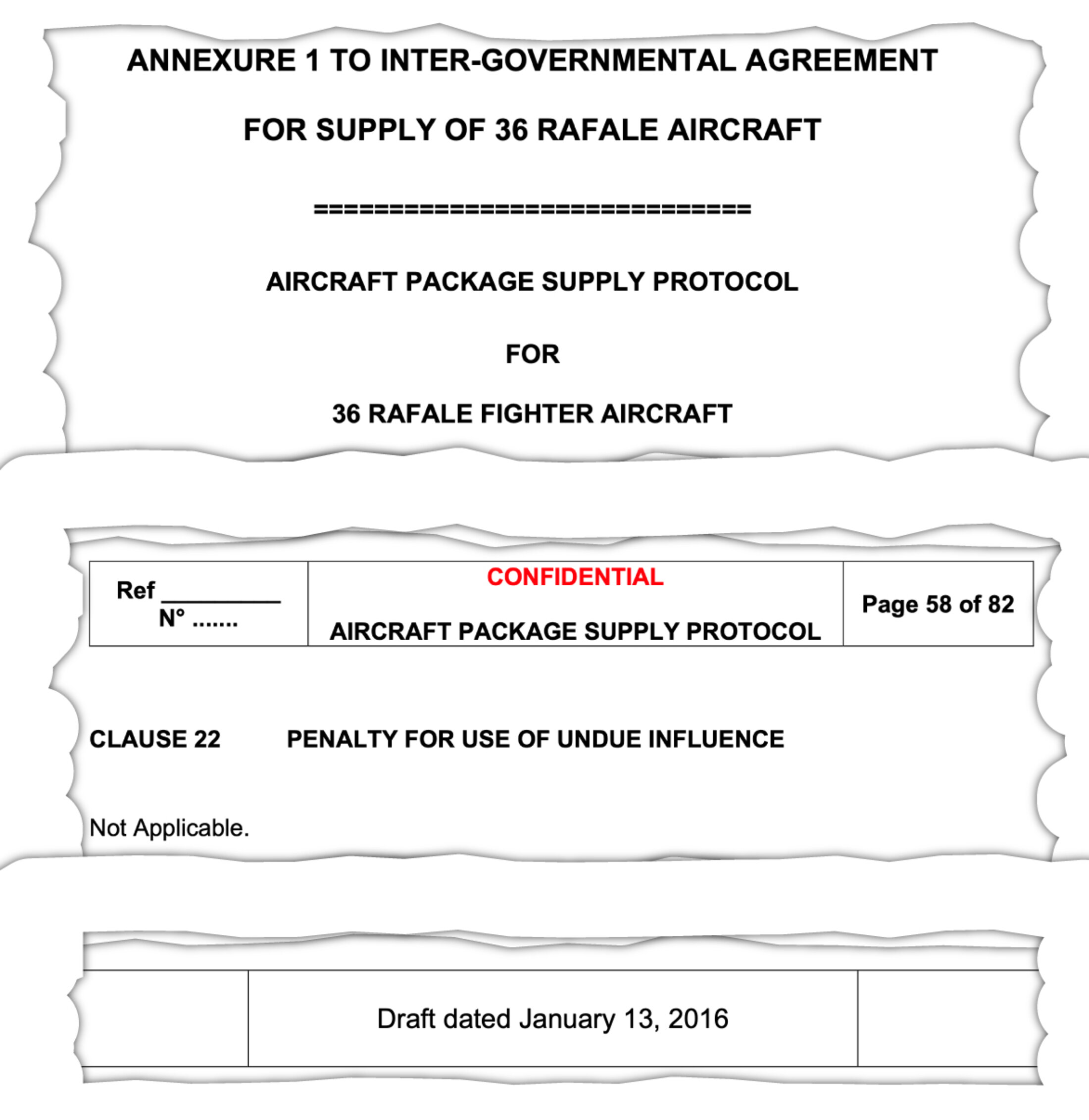

Enlargement : Illustration 4

Six months later, in the contract proposed on January 13th 2016 by the French team, concerning Dassault’s supply of the aircrafts, the two anti-corruption clauses were again marked “Not Applicable” (see document below).

Enlargement : Illustration 5

According to a report in The Hindu, the Indian authorities finally approved the removal of the clauses in September 2016, just before the signing of the final contract, at a meeting presided by the Indian defence minister, Manohar Parrikar.

Did his French counterpart, Jean-Yves Le Drian, also approve the removal of the anti-corruption clauses? Was he informed of the move? “In no case do we validate the information that you refer to,” commented a spokesperson for Le Drian, now French foreign affairs minister, adding that, “the inter-governmental agreement […] concerned only the requirements of the French government to ensure the delivery and quality” of the Rafale jets.

However, in the case of a sale agreed between two governments, the contracts are legally adjoined to the inter-governmental agreement. The heart of the negotiations was led, on the French side, under the direct authority of then defence minister Jean-Yves Le Drian, by a team of 11 people, made up of eight senior members of the French weapons procurement and export agency (the DGA) and the French air force, along with two representatives of Dassault and one for the MBDA.

Questioned by Mediapart, the MBDA replied: “MBDA does not habitually comment on negotiations concerning contracts.” Also contacted, Dassault declined to comment, as it has also declined to respond to all the issues raised in this report.

François Hollande, who was French president at the time of the events (in office from May 2012-May 2017), told Mediapart that he was “at no moment informed of these aspects of the negotiation”, and that he therefore could “not have approved an eventual removal of these [anti-corruption] clauses”.

- Secret commissions and overpriced contracts

To better understand why the French industrial partners wanted to remove the clauses, it is necessary to focus on the activities of Sushen Gupta, the commercial agent for Dassault and Thales. Gupta, who has US nationality, comes from an Indian family whose members have worked as intermediaries in the aeronautic and defence markets over three generations. Sushen and his brother were taught the business by their father, Dev Gupta, who is now retired.

The family’ consultancy firm, Indian Avitronics, works with a number of major aviation industry corporations, including several French groups. One of the latter is aircraft equipment manufacturer Safran, which notably makes the engines for the Rafale jets (see document below). Between 1997 and 2003, Safran paid 1.2 million euros into a Swiss-registered company belonging to the Gupta brothers. Contacted by Mediapart, Safran declined to comment on the subject.

Enlargement : Illustration 6

Sushen Gupta is known for his network of political and military contacts. In 2007, he boasted to a major Western aeronautics corporation that “contacts at all levels have been developed and maintained” with the Indian government. In the charges levelled against him, The Enforcement Directorate noted that he “had prior information about the future requirements of Indian Air Force, which is something not available in public domain”.

Dassault and Thales paid highly for Gupta’s know-how. They hired him at the beginning of the 2000s, at the very moment when India announced it was looking to buy 126 fighter jets. According to evidence from the ED’s casefile, the two French firms paid him several million euros over the 15 years leading up to the signature of the contract.

Enlargement : Illustration 7

The problem is that the money was not paid into the Indian-registered consultancy firm of the Guptas, but was instead transferred, in the form of secret commissions, some of which have questionable justifications, into offshore companies.

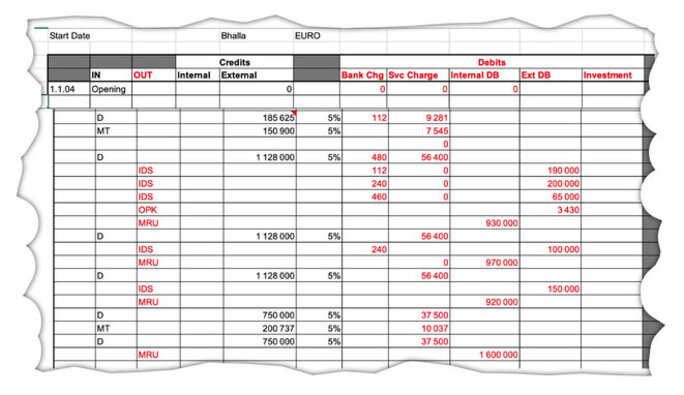

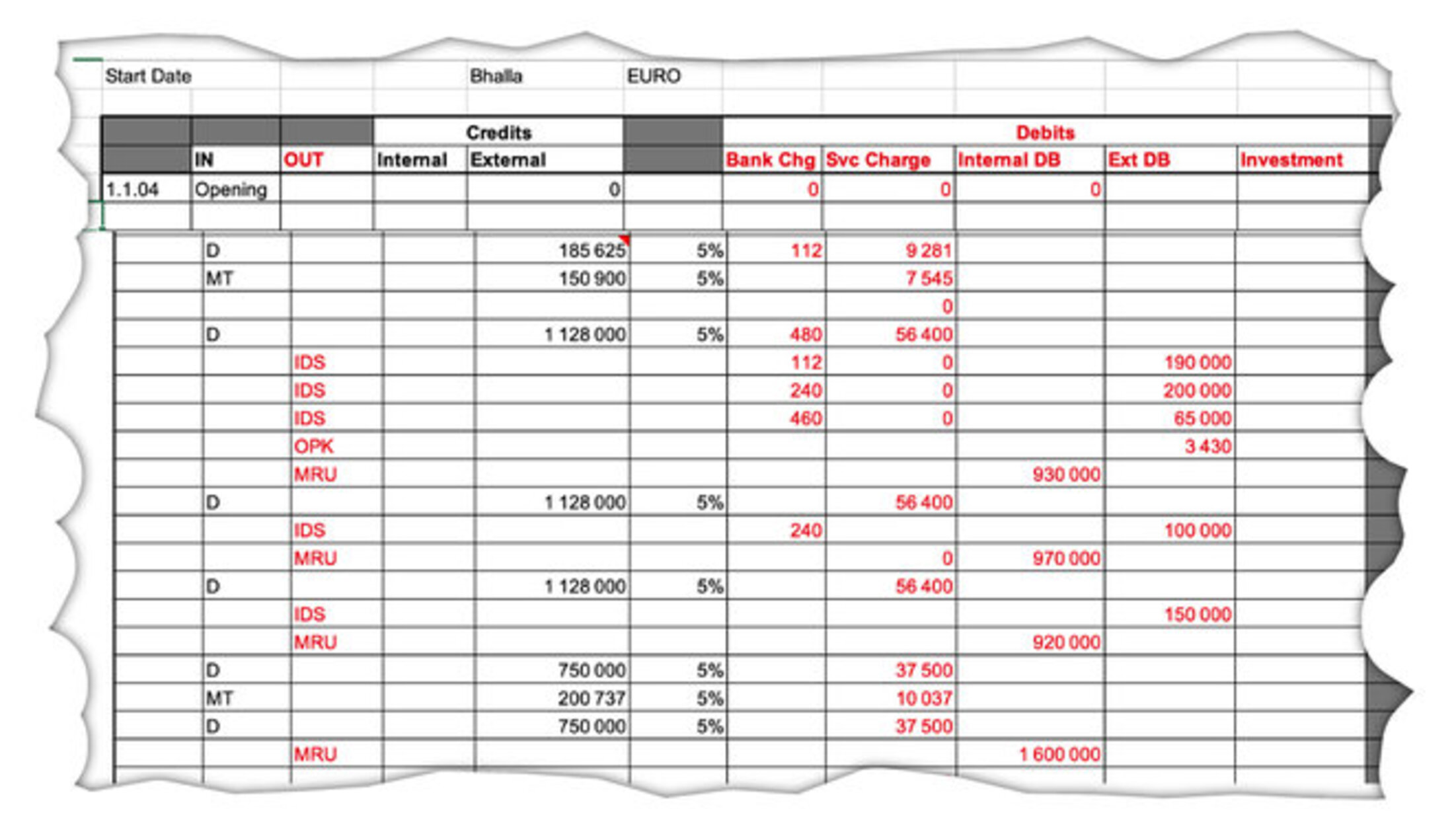

According to the Enforcement Directorate’s charge sheet, Thales ordered from the Gupta brothers “reports for various subjects” and the remuneration was paid into a shell company, with no offices or staff, registered in Dubai, which was managed by the lawyer for the Gupta family. According to an accounts spreadsheet belonging to Sushen Gupta, which only covers the years 2004 to 2008, Thales paid 2.4 million euros via this financial route. Contacted by Mediapart, Thales declined to comment.

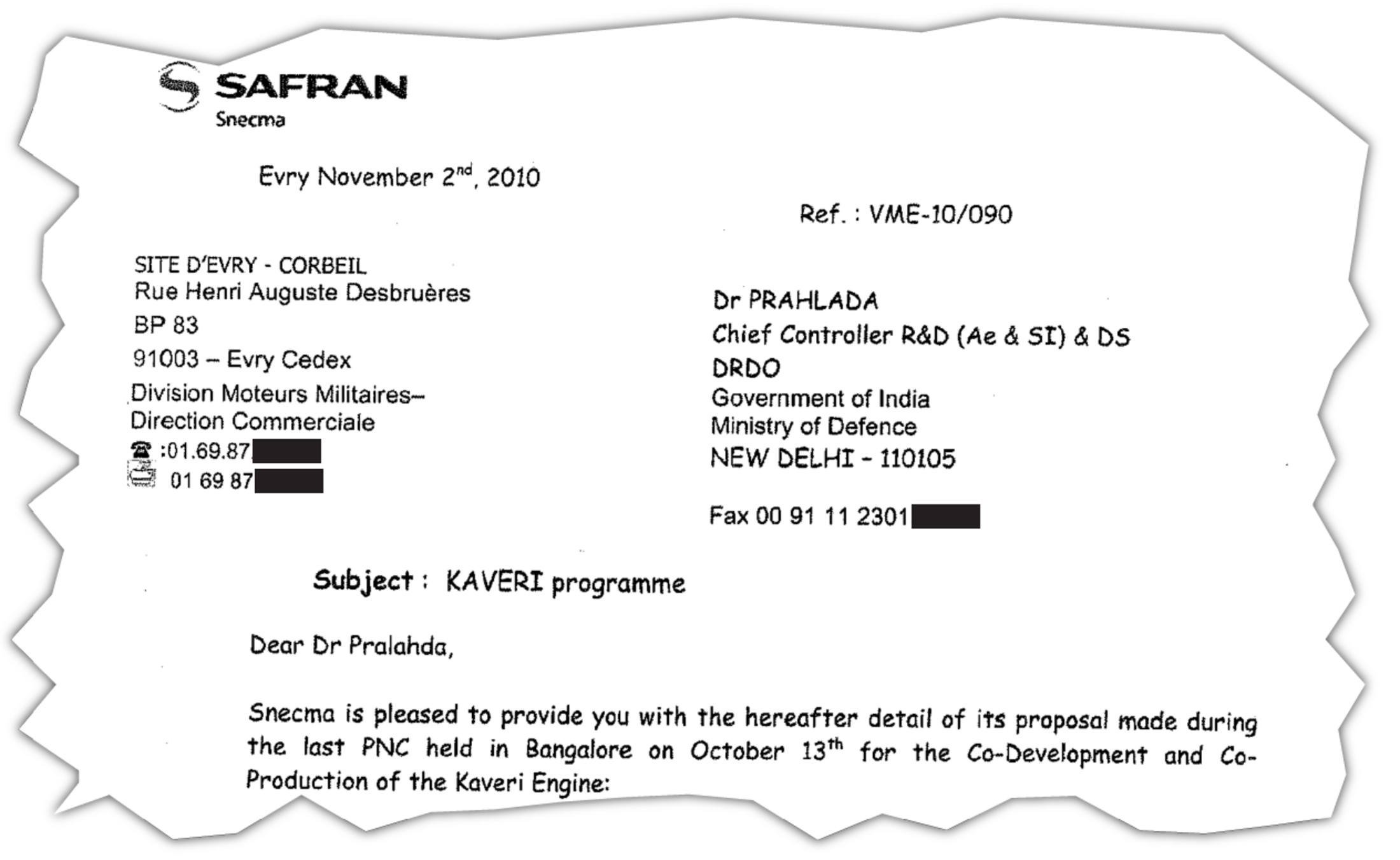

To receive payment from Dassault, Sushen Gupta used the same system he employed in the “Choppergate” scandal for which he now faces prosecution, involving an IT services company called IDS, where a member of his family worked. IDS obtained apparently inflated contract payments from Dassault, and in return would discreetly pay the middleman.

In a statement given to an Indian investigator, a member of the IDS management explained that it was an individual called “Pierre” at Dassault who instructed him to pay commissions into a fronting company registered in Mauritius Island called Interstellar. A Dassault company document (see below) shows that the French company placed 2 million euros-worth of orders with IDS in 2004, and planned to place 4.6 million more. Between 2002 and 2005, IDS transferred 900,000 euros to Interstellar.

Enlargement : Illustration 8

The financial scheme was subsequently changed. An IDS manager told the investigators that from 2004, Dassault placed orders for computer services with a Singapore-based company called Interdev, which was presented as a “System integrator for Dassault in Asia”. In reality, it was a shell company with no real activity, administered by a straw man for the Guptas who is currently on the run in South Africa.

Interdev paid IDS for IT services and transferred commission payments to Interstellar in Mauritius, under cover of sub-contracting work of a questionable nature. In the document reproduced immediately below, it is indicated that “Dassault has granted Interdev the right to sub-contract part of the agreement to Interstellar”, which is described as being “specialized in software […] and other IT services”. But in fact, the Mauritius-registered company was an empty shell, and is now wound down.

According to an accounts spreadsheet belonging to Sushen Gupta, an entity called simply “D”, which is a code he regularly used to designate Dassault, paid 14.6 million euros to Interdev in Singapore over the period 2004-2013. Interdev transferred just 2.6 million euros to the Indian IT services company IDS, while 11.9 million euros was transferred to Interstellar in Mauritius (see the document below).

Enlargement : Illustration 10

Questioned by Mediapart, Dassault declined to comment. Neither Sushen Gupta nor IDS responded to Mediapart’s attempts to contact them.

Even with the information from the spreadsheets, it is very difficult to ascertain where the millions of euros paid out by Dassault and Thales finally ended up, given the multiple offshore shell companies involved, registered in opaque tax havens like Switzerland, Liechtenstein and the United Arab Emirates.

Several million euros went into financing the Gupta’s comfortable lifestyle (including the purchase of two Porsche cars totalling 310,000 dollars and a marriage celebration costing 150,000 dollars paid in cash), along with investments, notably in the hotel business and property.

But there are also numerous payments to individuals, who are often designated on documents by their initials, and sometimes by codes, such as “A34”. The Enforcement Directorate investigators found trace of large cash withdrawals. One employee of Indian Avitronics, the Gupta family’s aeronautics consultancy firm, gave a statement to investigators in which he said that Sushen Gupta had given him cash with instructions to give it to certain individuals whose names, he said, he “did not remember”.

The Enforcement Directorate, in its written complaint detailing charges and evidence, suspects that part of the money was also used for “bribing officials in India” in the context of, “Various defence deals”. A confidential note found in the computer archives of the intermediary suggests that the Rafale deal may have been one of them.

- “People sitting in office asking for money”

It was on January 31st 2012 when Dassault won the tender issued by India for the supply of 126 fighter jets. But that was just the beginning of a process of negotiations necessary before the signing of a contract. In March that year, the Indian defence ministry launched an internal investigation into the results of the tender after a member of the Indian parliament claimed that the Rafale was more expensive than the Typhoon fighter jet proposed by Eurofighter.

A key point in the negotiations concerns the requirement made by India that Dassault would place half of the total value of the contract into Indian firms, such as buying from them aircraft components, in what is known as an “offset” agreement.

Under the initial contract, the state-owned aerospace and defence corporation Hindustan Aeronautics Limited (HAL) was to assemble, in India 108 of the 126 Rafale jets. Dassault chose as its principal partner in the private sector Reliance Industries Ltd (RIL), a group owned by billionaire Mukesh Ambani, even though it had no experience of aeronautic manufacturing. In February 2012, Dassault and RIL signed an agreement to create a joint-venture company in India that would provide Dassault with components.

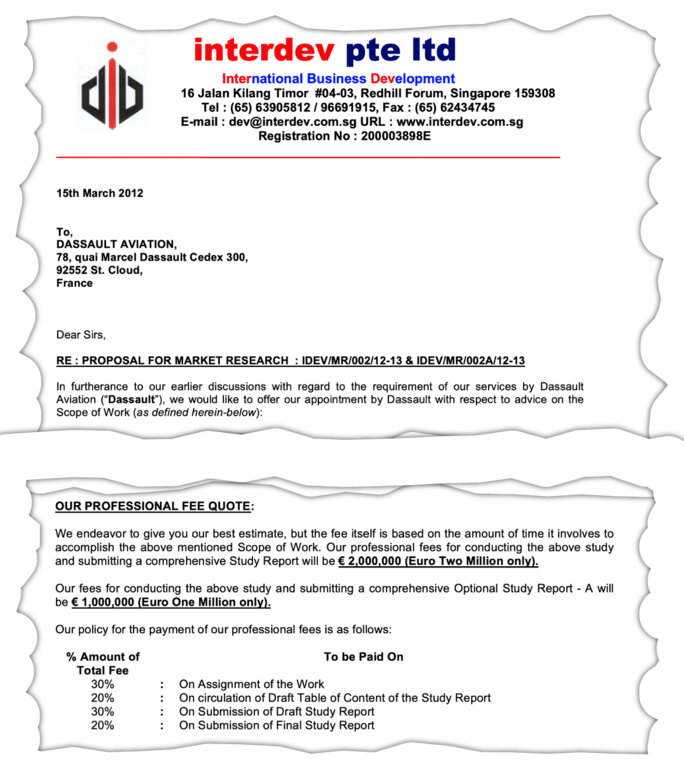

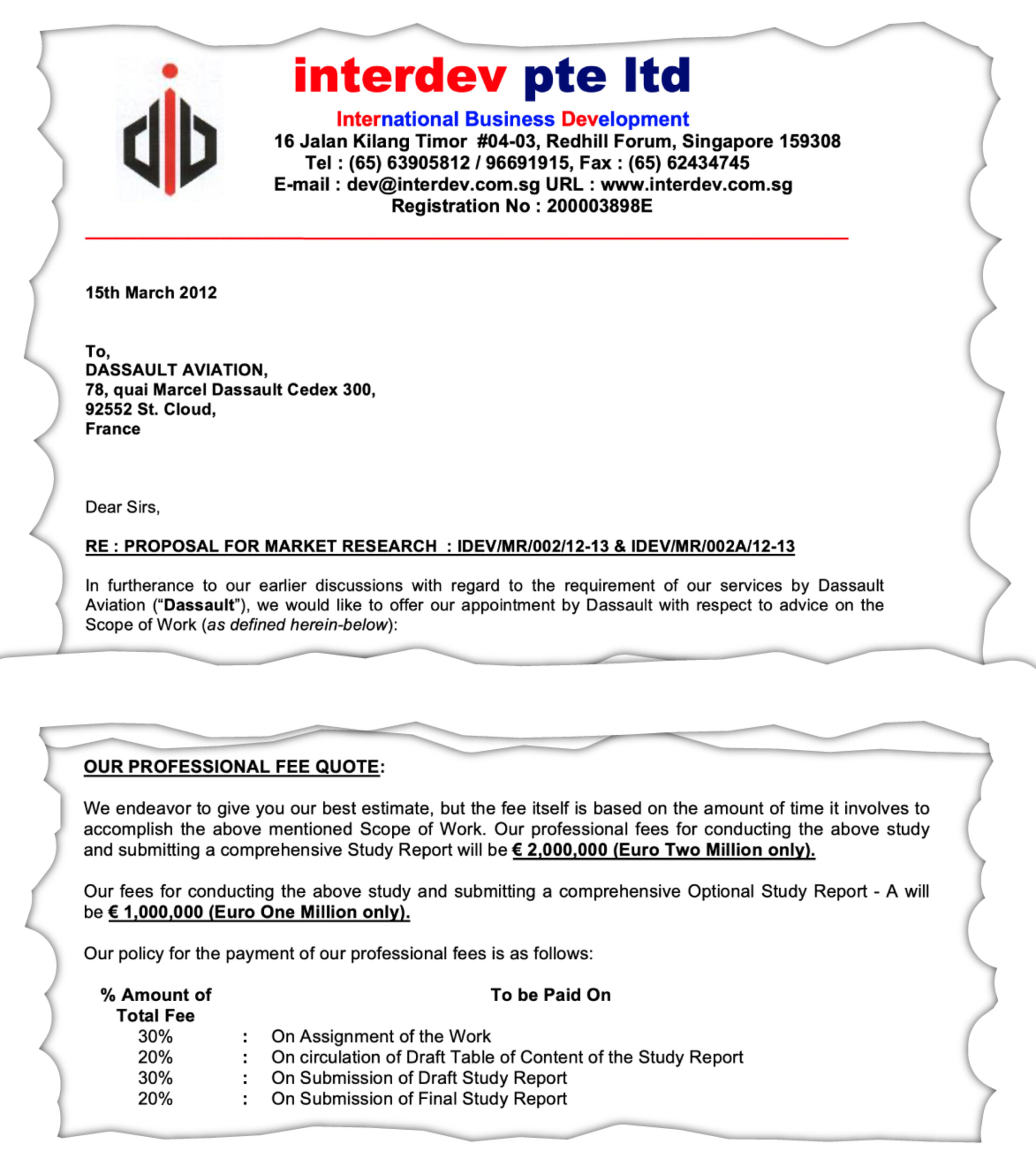

Sushen Gupta was involved in the process of selecting Indian industrial partners. On April 13th 2012, his Singapore shell company, Interdev, drew up three contracts for consultancy services for Dassault, for a total of 4 million euros. The work involved providing research reports on the defence market in India and identifying potential industrial partners (see document below).

Enlargement : Illustration 11

It is unclear whether the contracts were signed. According to a Gupta accounts spreadsheet, “D” made a payment of 500,000 dollars to Interdev five days later. But Sushen Gupta wanted more.

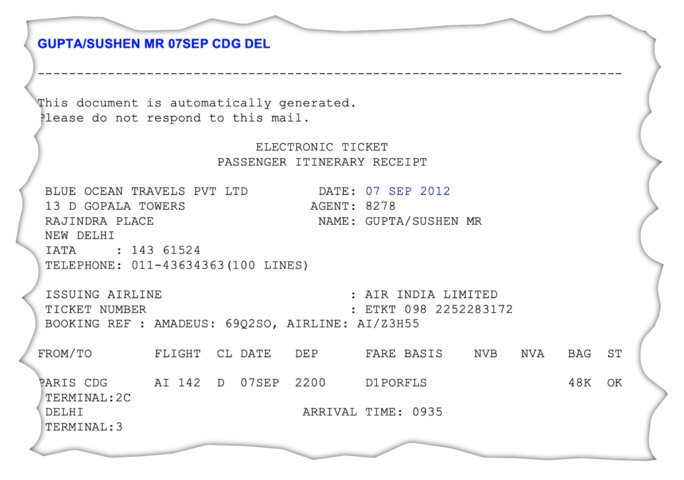

In his digital archives, there is a Word document containing what to all appearances was a message prepared for Dassault, written in the form of a bullet-points note. The document was modified for the last time on September 7th 2012 at 7.22am, and contained, on top of the message, an electronic ticket in the name of Sushen Gupta for a flight from Paris to New Delhi, which took off the same day at 10pm (see below).

Enlargement : Illustration 12

The contents of the documents suggest that Gupta had a meeting with Dassault Aviation, headquartered close to Paris, on September 7th 2012. In his notes, Gupta angrily wrote: “For the first time I am asking myself, why am I doing this? […] What is our fault? […] I have done what you wanted. We have come from India for some answers.”

The note might appear to suggest that money had been distributed by the Gupta’s to Indian officials and that Dassault had not compensated the payments: “The risk is taken,” he wrote, “you have an agent we have paid, now make sure it is legal clean and defendable we are not avoidable and must anticipate the worst. […] No money no decisions. So far you are happy because I have spent money? Now you are upset because you have to pay? […] Now is not the time to fight. You should not have started, now finish.”

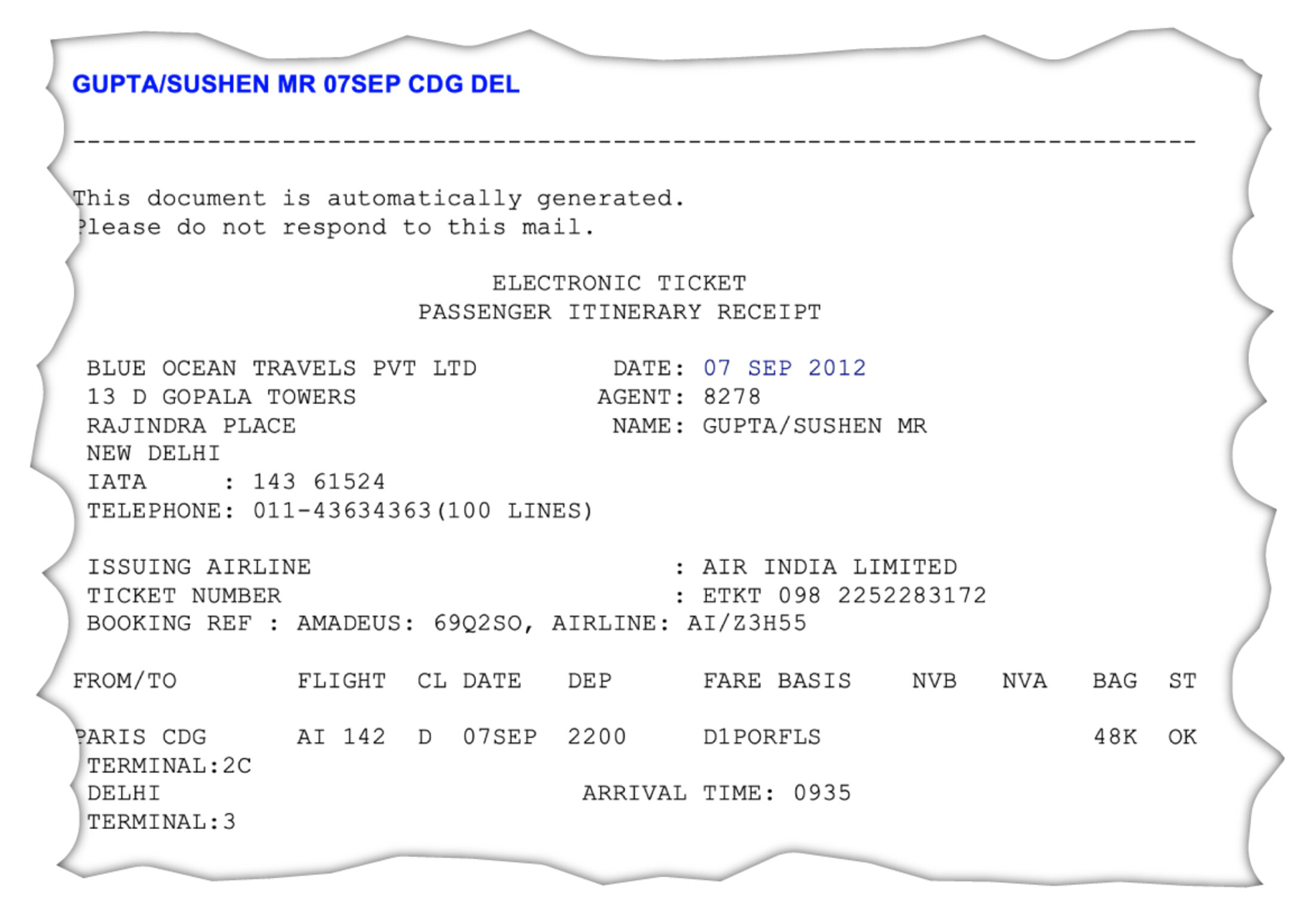

Further down the document is a more explicit series of bullet-point notes (see below): “Cannot stop now too late for me, I owe people money and commitments. […] People sitting in office asking for money. […] Sushen, he promised because you promised. […] People [are] demanding what do we do? […] Those people will, if we don’t pay, put us in Jail and RIL [Reliance Industries Ltd] will exit – then we are really finished, deal scrapped as per commitment of RM [editor’s note, defence minister Rakhsa Mantri] in Parliament.”

Enlargement : Illustration 13

The intermediary saw no risk in the payments, noting: “Cash from elsewhere, not connected. What is the worry?” He also suggested to Dassault to ask for a contribution from its Indian industrial partners: “What have other Indian companies done to deserve the work?”

While Dassault offered no comment about the notes or the existence of a meeting with Sushen Gupta, the latter did not respond to Mediapart’s attempts to contact him.

What is established is that Gupta continued to be a strategic consultant for Dassault and that, three years later, he obtained confidential Indian defence ministry documents about the Indian negotiating team’s position on the Rafale contract.

- The intermediary obtained confidential documents from the Indian defence ministry

In 2014, the negotiations over the Rafale contract became bogged down, notably because of disagreements between Dassault and the state-owned aerospace and defence corporation HAL.

On May 12th 2014, the Indian National Congress party lost power in the country’s general elections and Narendra Modi, head of the ultra-nationalist Hindu BJP party, became prime minister. In a note he sent to Dassault, dated June 24th 2014, Sushen Gupta raised the possibility of a “meeting with Indian political high command”. Clearly well informed, he also reported that the Indian defence minister was to be replaced “before end of July”. In the event, the minister was replaced that November.

Enlargement : Illustration 14

On April 10th 2015, following a meeting in Paris with then French president François Hollande at the Élysée Palace, Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi made the surprise announcement that the tender for 126 fighter jets had been overturned, and that India now wanted to purchase 36 Rafale jets, built in France and “ready-to-fly”, in a contract to be agreed between the two states.

It was a major turnaround; the state-owned company HAL was removed from the deal as was also Mukesh Ambani’s group Reliance Industries Ltd. The latter was replaced by the group Reliance ADAG, owned by Mukesh Ambani’s brother Anil Ambani, a close acquaintance of Modi (see more in Mediapart’s previous investigations here and here ).

Because the Rafale deal would now be an inter-governmental agreement, the negotiations were led between the French and Indian defence ministries. On the French side, under the authority of then defence minister Jean-Yves Le Drian, the negotiating team included eight senior defence ministry and air force staff, two Dassault executives, and a representative of missile manufacturer MBDA.

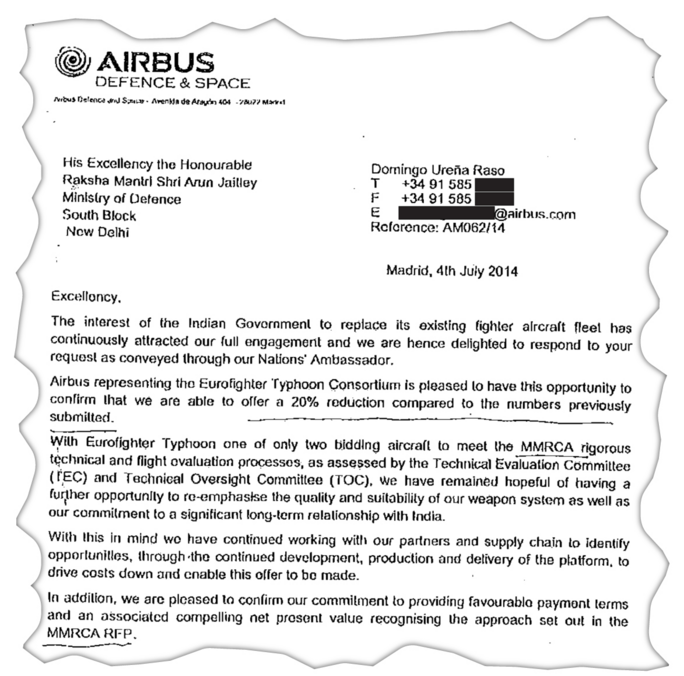

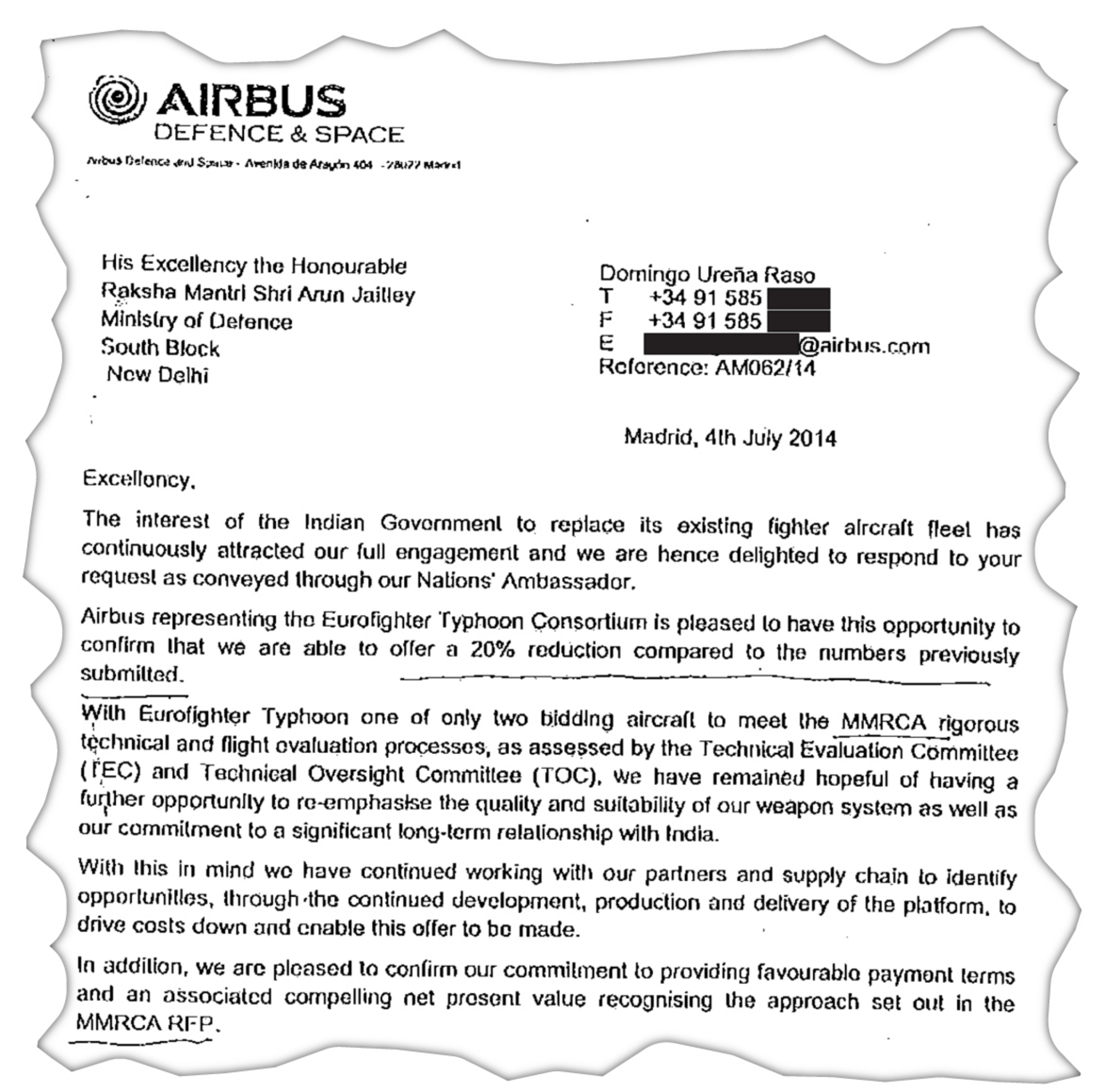

One of the key issues was of course the purchase price of the aircraft. On May 13th 2015, the Indians demanded, as France had promised, that the cost of the Rafale jets should be the lowest ever offered by Dassault. The Indians had a trump card to play, which was that in July 2014, the European consortium Eurofighter, which lost out in the original tender, had presented a new offer to India, knocking down the price of its Typhoon jets by 20%.

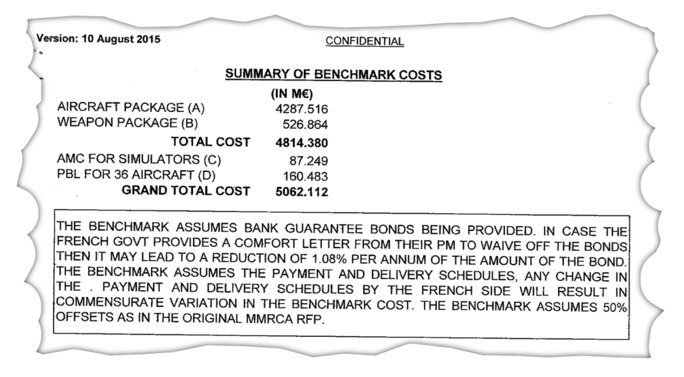

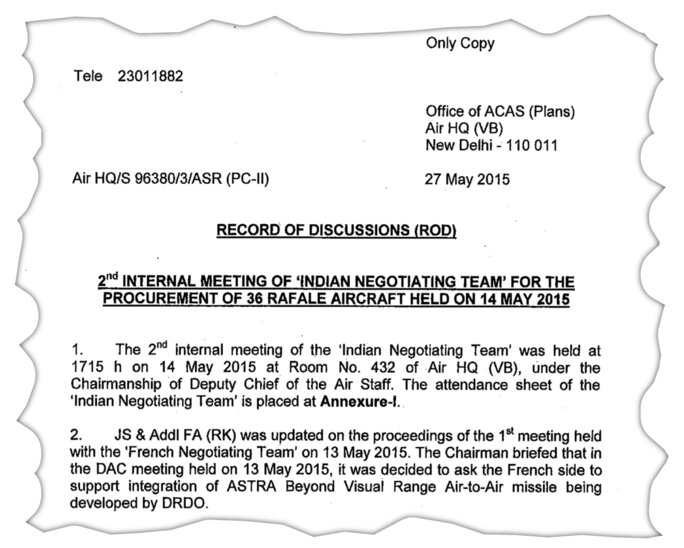

The situation rapidly became a confrontation between the two sides. After performing complex “benchmark” calculations, the Indian negotiators concluded, in a confidential report dated August 2015, that the overall purchase price for the Rafale jets, including their weaponry, should be 5.06 billion euros (see the document below). But in January 2016, Dassault proposed more than double the price: 10.7 billion euros, and excluding the missile equipment.

Enlargement : Illustration 15

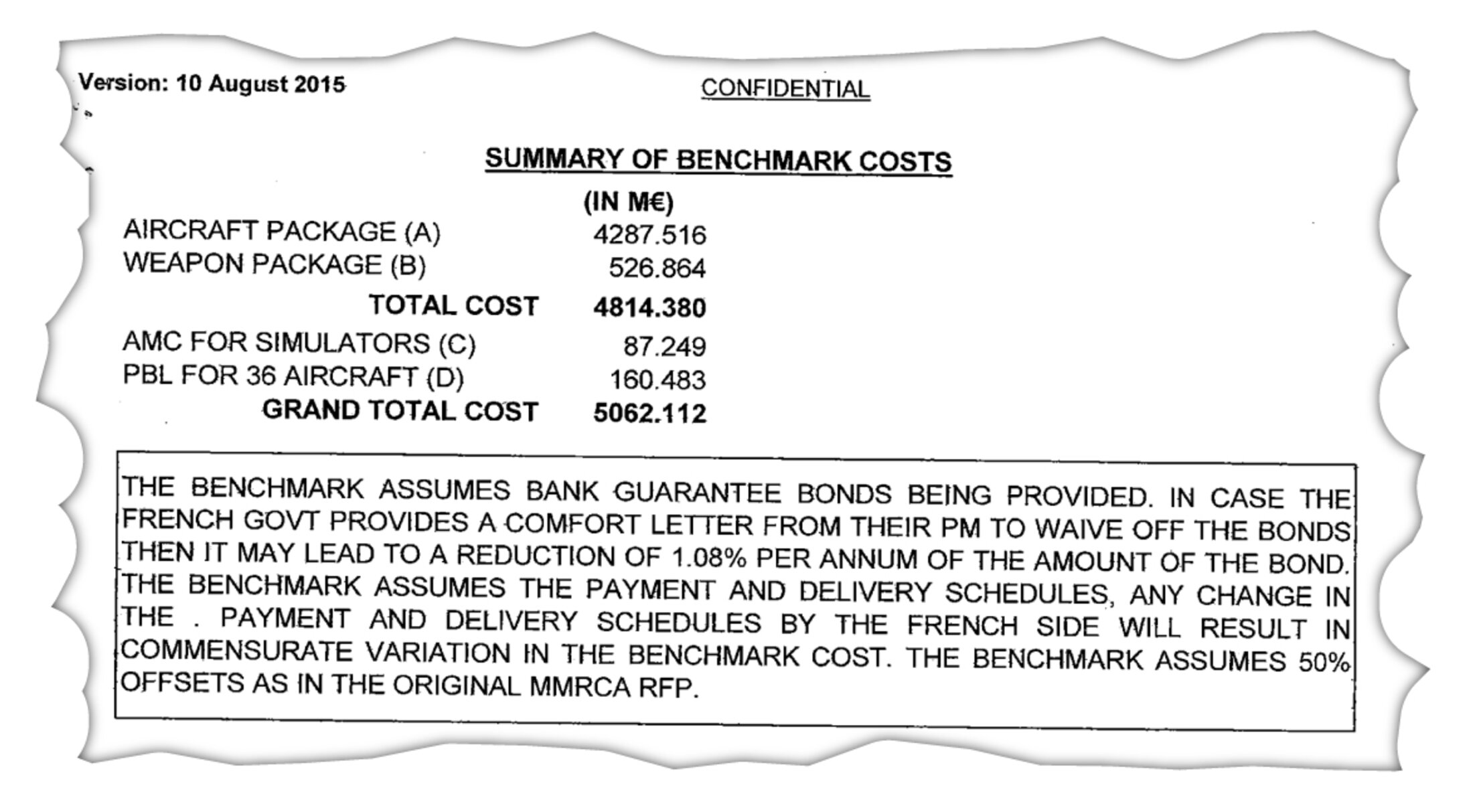

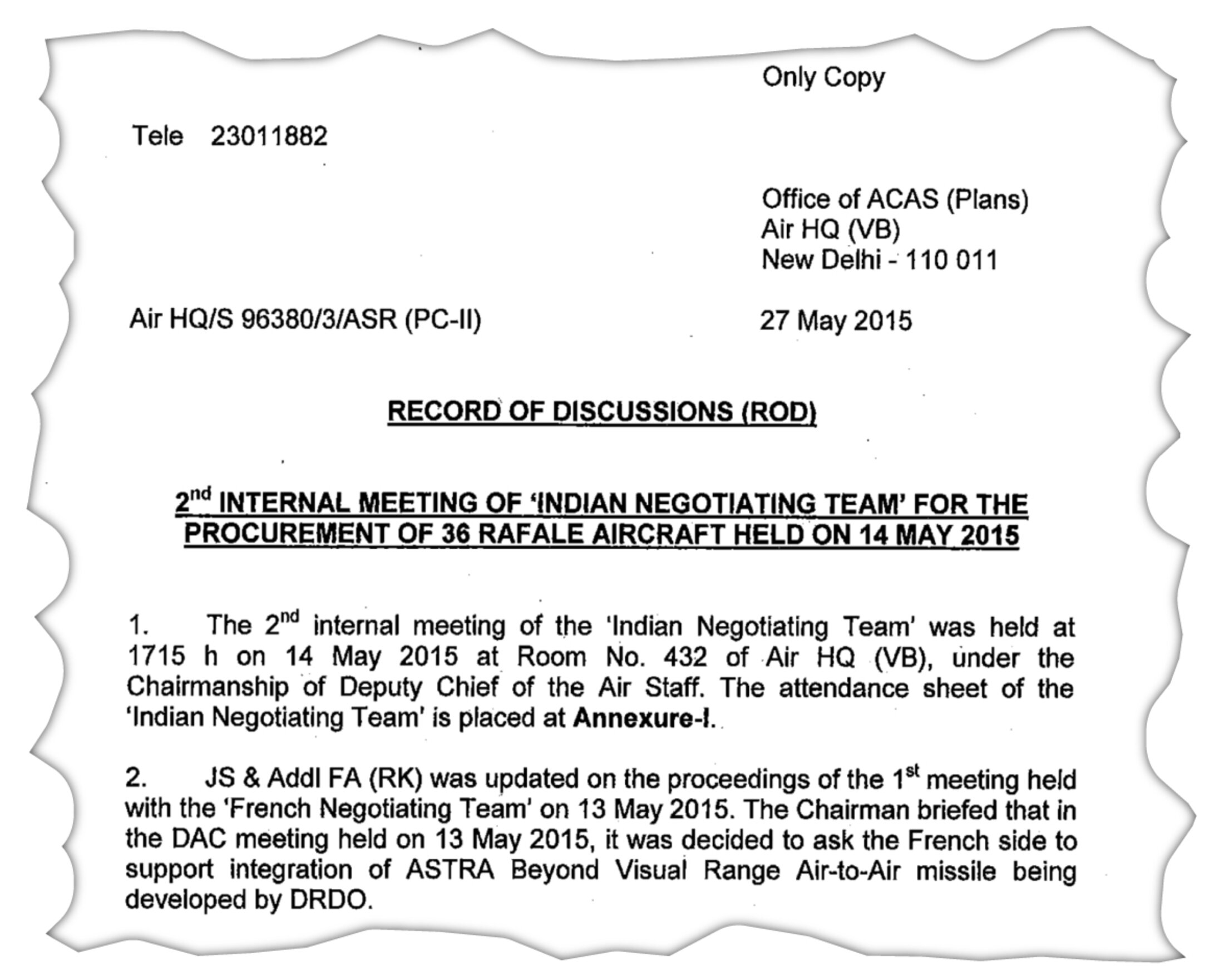

For the French camp, Sushen Gupta’s assistance was to prove precious. According to information gained by Mediapart, he obtained confidential documents from the Indian defence ministry on the subject of the dispute over the purchase costs (see below). These included the minutes of meetings by the Indian Negotiating Team (INT), the arguments they had prepared to present to the French, and detailed notes on the calculations of the costs (“benchmarking of costs”) and the methodology employed. Gupta even obtained an Excel sheet created by one member of the INT for calculating the purchase price (“price benchmarking”).

Enlargement : Illustration 16

The intermediary also obtained the complete contents of the revised Eurofighter offer as it had been presented by Airbus (a member of the consortium) to the Indian defence ministry in July 2014 (see an extract of this below).

Enlargement : Illustration 17

Questioned by Mediapart about the documents obtained by Sushen Gupta, the Indian defence ministry did not respond.

The intermediary had gathered all the information needed for the French to counter the Indian team’s demands. He took an active part in Dassault’s strategy, calculating on computer spreadsheets what the best deal might be. On one of these, created on January 20th 2016, one of the columns concludes a suggested overall purchase cost of 7.87 billion euros. That was precisely what the French negotiating team proposed to the Indians during a negotiations meeting the following day. But the Indian side again demanded a lower price, and after the French refused, the meeting was called to an abrupt end.

Four days later, on January 25th 2016, then French president François Hollande was in New Delhi to sign a protocol agreement with Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi, amid grand ceremony, for the sale of the 36 Rafale jets. But the agreement was a non-binding political one. Hollande declared that the negotiations were “progressing”, but in fact they had become blocked.

An article published in English in May 2016 by French website Intelligence Online (IOL) reported that Thales had engaged Gupta’s services to “woo” Modi’s Hindu nationalist BJP party in order to unblock the situation. “Thales made sure it had the support of Dev Mohan Gupta, who heads Indian Avitronics,” IOL reported, adding: “[…] Gupta's sons Sushant and Sushen are on good terms with President of BJP Amit Shah, the finance minister Arun Jaitley and the head of the Indian air Force, Arup Raha.”

The contract was finally definitively signed on September 23rd by Indian defence minister Manohar Parrika and his French counterpart Jean-Yves Le Drian. The Indian authorities had finally accepted the French offer of a total cost of 7.87 billion euros, a sum they had rejected six months earlier.

Enlargement : Illustration 18

That final deal did not meet with unanimous satisfaction at the Indian defence ministry, to the point where three of the seven members of the Indian Negotiating Team (INT) signed a confidential report highlighting anomalies they said they had noticed.

In the document, revealed by The Hindu, they notably denounced the change that was brought about in the calculation of costs which, they argued, ended up with a purchase price that was too favourable for Dassault. They also argued that the Eurofighter was a cheaper option.

Those conclusions were contradicted by the office of the Comptroller and Auditor General of India, the CAG, which found that the final cost of the Rafale jets was 17% less than the initial tender offer. Meanwhile, the Indian Supreme Court ruled in 2019 that there were insufficient grounds for opening an investigation into the matter. But that decision was made without the information gathered in the AgustaWestland probe by the Enforcement Directorate.

For Dassault, the deal ended very well, and Sushen Gupta was once again rewarded. In March 2017, one of the Gupta family’s Indian companies, Defsys Solutions, invoiced Dassault for 1 million euros for the production of 50 replica models of the Rafale jet (see more on this in the first of this three-part report).

Defsys Solutions also became, as announced in a statement released by Dassault, one of the sub-contractors to the Rafale deal. Dassault declined to disclose to Mediapart the nature or the cost of that contract.

-------------------------

If you have information of public interest you would like to pass on to Mediapart for investigation you can contact us at this email address: enquete@mediapart.fr. If you wish to send us documents for our scrutiny via our highly secure platform please go to https://www.frenchleaks.fr/ which is presented in both English and French.

-------------------------

- The original French version of this article can be found here.