The history of Soviet dissidents still speaks to us today. Theirs is not some long-forgotten tale from a world which vanished when the Soviet Union collapsed in 1991. For their story stands as a lesson, or at least a possible instruction manual, for people who continue to fight for basic rights in Russia, Turkey, China, Algeria and many other countries.

Those are your lasting impressions as you leave Bessèges, a village in the Cévennes National Park in the south of France. This is where 83-year-old Tatiana Plyushch lives in a small narrow house. Its front gives out onto a high street where the shops have long since closed, while the rear looks out onto a long garden which has been slightly neglected since the death of her mathematician husband and Soviet dissident Leonid Plyushch in 2015.

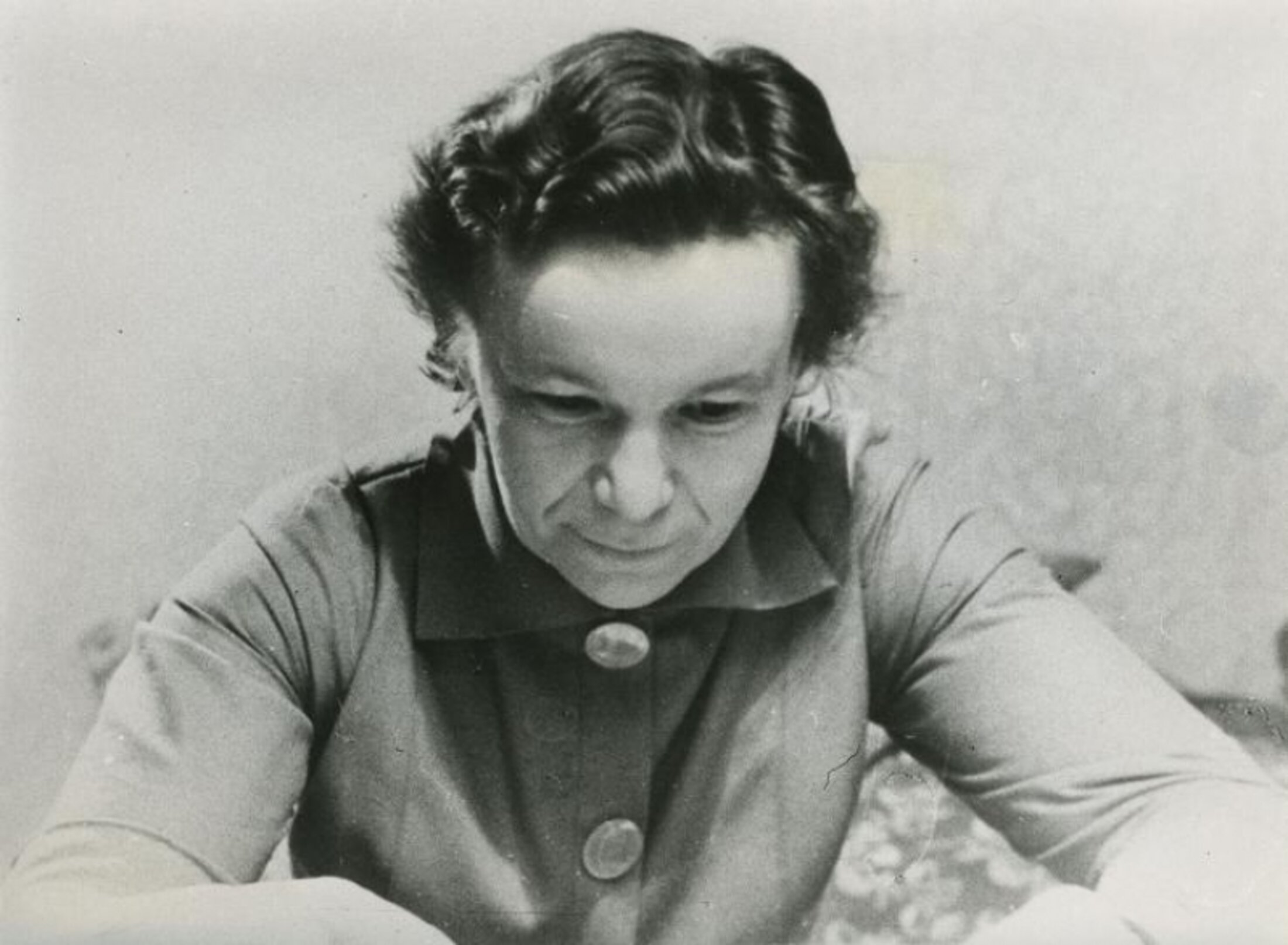

“We tried to do everything in a responsible manner. You have to choose your life. Yet we couldn't live like that, it was impossible. The only response to hypocrisy and lies is to live with self-respect,” she says, in a French interspersed with a few words of Russian or Ukrainian. Tatiana Plyushch has retained that direct and determined gaze that you see in all her photos from the 1970s. And while some memories now get a little muddled, her observations remain sharp.

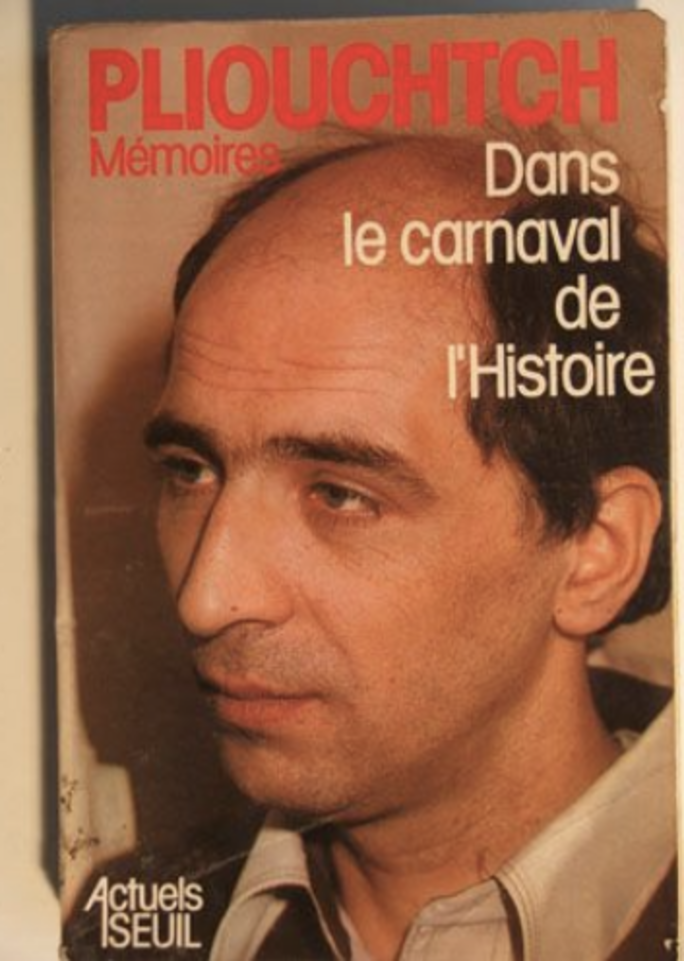

Enlargement : Illustration 1

Tatiana's granddaughter, Julie Plyushch, sums up her grandmother's life of struggle her own way. “As a young girl I used to ask: 'Granddad was imprisoned, and why was he freed?' And I was told: 'Because your grandmother frightened the KGB!'” But first we need to go back to the end of the 1950s, to Odessa, the major Ukrainian port on the Black Sea, and to the surrounding countryside.

At the age of 22 Tatiana Plyushch had just been appointed as head teacher of a nursery school. She met Leonid who had also just got his first post, as a teacher in a rural primary school. The two young people discovered the huge deprivation suffered by the Ukrainian people. “I saw how people lived, they had nothing and every day at school I had to make sure that the food wasn't stolen,” she recalls.

“The first thing that struck me was the deep misery of the peasants. A third of the village's inhabitants were weakened by tuberculosis … Men's conversations mostly revolved around drink, women's were about the vegetable patch allocated by the kolkhoz [editor's note, Soviet collective farm],” wrote Leonid in his 1977 autobiography 'Dans le Carnaval de l’Histoire' published by Éditions du Seuil, and published in English as 'History's carnival: a dissident's autobiography' in 1979.

A year later the couple got married and left for Kiev to continue their training. Tatiana enrolled in a major teaching institute. Leonid went on to become a mathematician in a cybernetics institute. Passionate about knowledge, and also bulimic, Leonid read philosophy voraciously, and became a specialist in Yogic texts and telepathy. But life was tough for the young couple as they started a family.

“We lived in a cellar; finding enough to eat with two children was very hard. Everyone was used to living like that, without money,” said Tatiana. But Kiev, like all the major Soviet cities, was in a state of turmoil. The denunciation of Stalin's crimes in 1956, which is seen as the “thaw” introduced by the new Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev, was not just a huge shock. People also felt free to talk and there were endless discussions.

“We thought a great deal. And then there were the libraries, we read everything, we devoured foreign books. I've always read an enormous amount but that period was exceptional,” she said. Becoming an opposition figure was a long, gradual process. At university Leonid Plyushch was an enthusiastic leader in the Komsomol, the community party's youth organisation. He was a brilliant student and even applied to enrol in the KGB training school. But he was refused because of bone tuberculosis which he had contracted when very young and which had left him disabled in one leg. Tatiana's father, meanwhile, was a soldier in the Red Army who lost his three brothers in the war and loyalty to the party was not up for debate.

But by the start of the 1960s the joys of communism had come to acquire the bitter taste of terrible failure. “It arrived progressively, we discovered life, philosophy, Kiev's intellectual circles,” says Tatiana. Leonid, who came from a family with peasant origins, continued his exploration of the countryside. There he discovered memories of the holodomor, that terrible famine of the years 1932-1933 in Ukraine. This was caused by the Soviet regime through its policy of arresting, deporting or executing kulaks - wealthier peasants - and led to around 5 million deaths.

From afar the couple also discovered Moscow, its debates and its dissidents. The telephone was constantly busy and as Kiev was a day away by train the city sometimes served as a temporary refuge for a few intellectuals who were too at risk in Moscow. Clandestine literature percolated its way through Kiev. “In my institute people spoke about all that and without fear,” says Tatiana Plyushch. “We swapped books, texts, samizdats [editor's note, underground publications], all that material.” An unspoken rule developed. When a book or clandestine text was loaned the recipient of course read it, but also made a copy of it. That way the books could spread quickly. “I spent whole nights tapping away at the samzidat machine. I was not particularly militant but that interested me,” Tatiana explains.

'I didn't think about the future, it was closed off'

Without doubt the turning point for the couple was 1964. They went with their eldest son to an “opposition gathering” at Baby Yar. Baby Yar is a ravine in Kiev where the Nazis exterminated 34,000 Jews during September 29th and 30th 1941. Those massacres continued over the following months, with between 100,000 and 150,000 people killed in all. This central event in the mass shooting of Jews in the Holocaust was concealed by the Soviet regime. The specific character of the Jewish genocide was not just denied, anti-Semitic policies in fact continued under Stalin, drawing on an historic anti-Semitism that had existed in Ukraine.

In her remarkable 2007 book 'The Soviet Union and the Shoah', Antonella Salomoni recalls that in “1962 the Baby Yar ravine was covered by several tons of earth, a major route crossed it and some residential buildings had been constructed in the vicinity”. It was only in July 1976 that a monument was finally put up. The inscription read: “Here in 1941-1943 the German fascist invaders murdered more than a hundred thousand Kiev citizens and prisoners of war.” There was no mention of the Jews.

In 1961 the famous Russian poet Yevgeny Yevtushenko was allowed to publish his poem Baby Yar (read it here in English). That led to him being violently attacked in the official press. Tatiana Plyushch herself knows what anti-Semitism means; her father was Jewish. “At the age of 16 I had to get a Soviet passport and I took my father's name. We all knew that was problematic,” says Tatiana. Leonid also wrote about how Jews were systemically banned from being hired in his research laboratory. “This practice made me angry and I protested about it very loudly,” he wrote.

It was in 1964, the same year they went to Baby Yar, that the couple were questioned by the KGB for the first time. Khrushchev had been removed from office in October that year and Leonid decided to write a long letter to the party's central committee. “The headline on the first part of it was 'That's enough!'. We'd had enough of seeing the Soviet government dishonouring the country, enough of personality cults, enough of anti-Semitism etc. The second part was headed 'We demand!',” he stated in his book.

Was he aware of the dangers involved? The letter was sent to a friend in Odessa who was supposed to make sure it was sent to the central committee. But it was intercepted by the KGB who arrested and interrogated Leonid Plyushch at length. Tatiana was also picked up at the same time. “I didn't think such a letter served any purpose but Leonid had the right to write it … I didn't agree with everything, I wasn't a Marxist at all, I'd never wanted to join the party. In the 1960s I was closer to [the views of Aleksandr] Solzhenitsyn [editor's note, the novelist and political prisoner] which I'd read in a samizdat,” she recalls.

The episode meant that the couple were now known to the authorities. But this did not stop them immersing themselves in action. Leonid made more trips to Moscow where he met all the city's dissidents. He got hold of books by writers Andrei Sinyavsky and Yuli Daniel after they had been convicted of anti-Soviet agitation and sent to work in the forced labour camps known as the Gulags. Through her work at the teaching institute Tatiana Plyushch travelled throughout Ukraine and built up her contacts.

In particular the couple discovered Ukrainian nationalism. This was primarily through Ukrainian literatures and especially poetry. The great Ukrainian critic Ivan Dziuba became a close friend. “By chance I was born in Moscow but my parents were living in Kharkov [editor's note, Ukraine's second biggest city]. Leonid and I met the many Ukrainian nationalist groups that existed. There was already talk of independence. And I also love the Ukrainian language a great deal,” says Tatiana.

The Soviet regime had just one argument against this reawakening of Ukrainian nationalism, which was to portray it as the work of “fascist Banderite vermin”. This was a reference to Stepan Bandera, the far-right Ukrainian nationalist who had collaborated with the Nazis in 1944. The same argument was used by the current Russian leader Vladimir Putin during the Orange Revolution in Ukraine in 2004, and then again during the 'Maidan' protests that sparked the Ukrainian Revolution in 2014, and at the outbreak of war in the east of Ukraine.

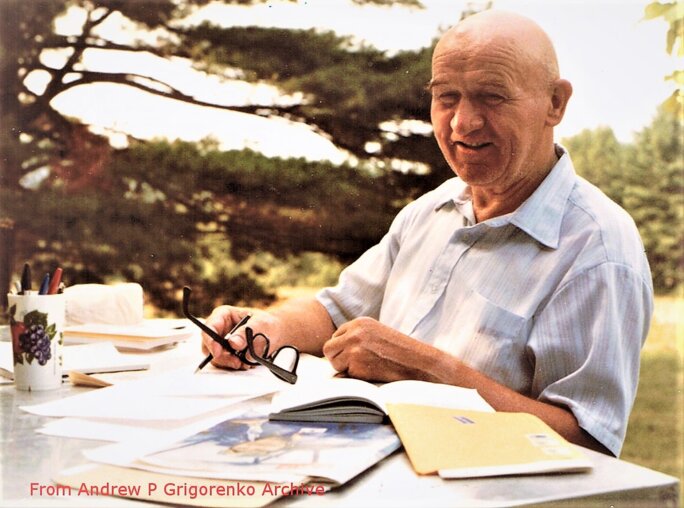

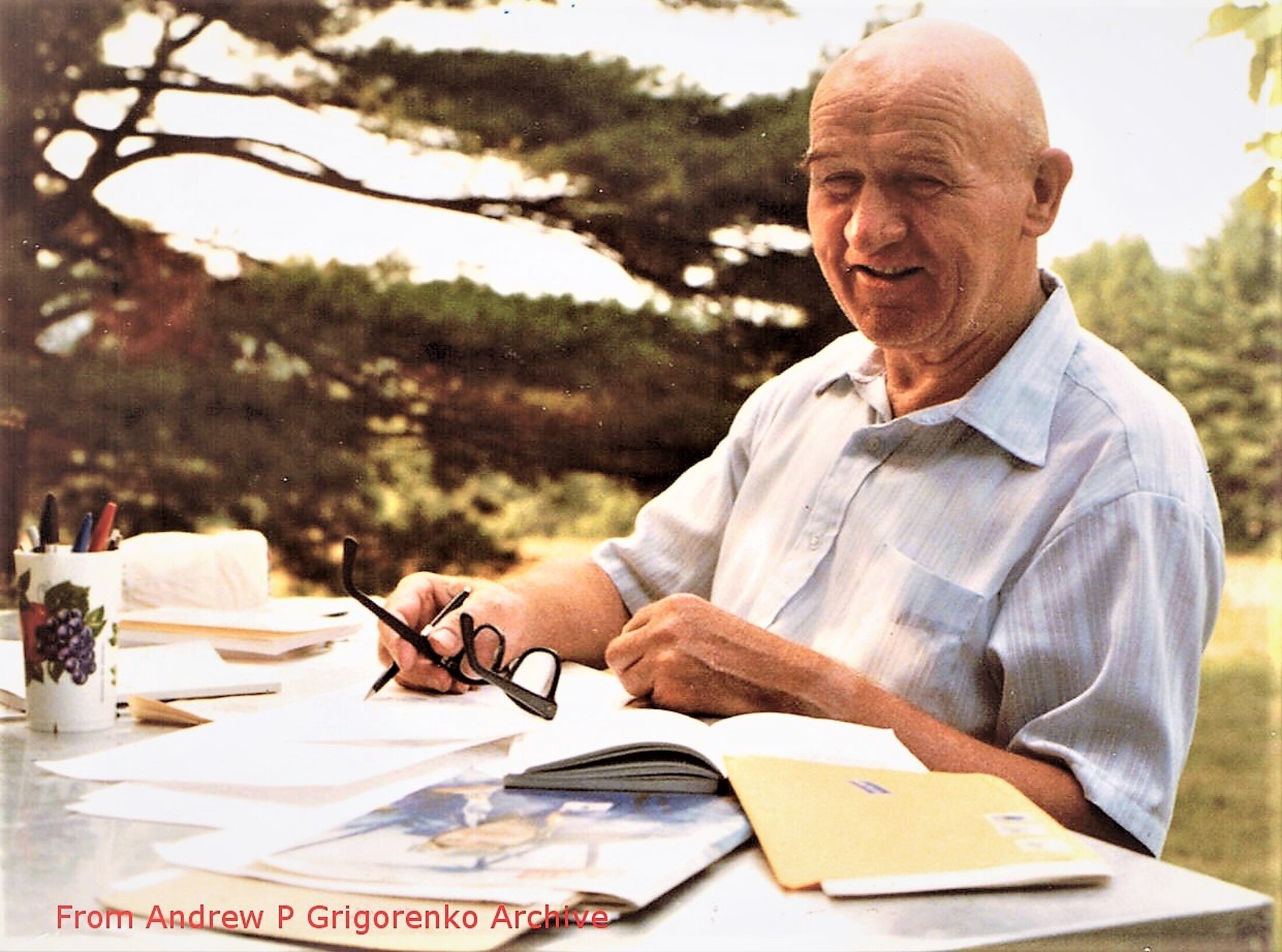

Enlargement : Illustration 4

Yet these movements are far more diverse than that, and also driven by demands for democracy and often linked to the struggle of the Tatars in the Crimean. Many of these had been deported to Uzbekistan or sent to camps in Siberia in 1944, on the orders of Stalin. “The Tatars that we met were extremely cultivated and interesting. General Petro Grigorenko [editor's note, a Ukrainian and another leading dissident] worked a great deal for their cause,” says Tatiana.

At the start of the 1970s the Soviet regime under Leonid Brezhnev decided to step up the repression of dissidents. More trials were held and more dissidents were locked up in psychiatric hospitals. At the time Yuri Andropov headed the KGB and his own Fifth Directorate, which was especially set up to track dissidents (the literal translation of the Russian word means 'those who think differently'), was working at full capacity.

Leonid Plyushch was arrested on January 15th 1972. “We were expecting it, in the days leading up to it lots of people had been rounded up, we told ourselves that Leonid would be on the list,” recalls Tatiana. Four years earlier the mathematician had been hounded out of his work for having circulated - via a samizdat - an open letter he had written to the newspaper Komsomolskaya Pravda in March 1968. In the letter he had expressed his anger at the newspaper's coverage of the 1967 trial of journalist and poet Alexander Ginzburg and poet Yuri Galanskov, dissidents who were subsequently sent to labour camps.

The following year, in May 1969, Leonid Plyushch was one of the founder members of the Initiative Group for the Defence of Human Rights in the USSR. The group sent a letter to the United Nations denouncing the repression that was taking place, a move which provoked a scandal.

For Tatiana Plyushch it was the start of a long struggle. “It was very hard but you had to keep going. I wasn't thinking about the future, that was closed off,” she recalls. Two months after her husband was arrested she learnt that her institute's management board was looking at her. She was described as a “Zionist” and criticised for her “antisocial lifestyle”. Support within the institute protected her, but Tatiana later decided to resign so that she would not put her supporters in danger.

The young woman now fell into a black hole of repressive bureaucracy; traipsing from counter to counter to get scraps of information; being followed; questions and requests left unanswered; the threat of being separated from her children; constant provocations.

But this was no longer the days of the Great Terror under Stalin and Tatiana Plyushch, like many other dissidents, began a “battle of the law” In other words, they demanded that the authorities applied the letter of their own laws, to turn into reality the formal rights that were set out in legislation which the authorities themselves cared nothing about.

'You are my husband's torturer'

A network of friends in Kiev supporter and advised her. “One woman helped me a lot and that was Tatyana Khodorovitch. She very quickly called me from Moscow, told me she was coming, and stayed with me and helped me with numerous matters,” says Tatiana Plyushch. Tatyana Khodorovitch, a linguist who was sacked by the Russian Language Institute in Moscow, was to become a key figure in the Plyushch affair.

She, too, was a member of the Initiative Group for the Defence of Human Rights in the USSR, and proved a permanent source of support for Tatiana Plyushch, forming a link with dissidents in Moscow, especially the physicist and human rights campaigner Andrei Sakharov and his wife Yelena Bonner. It was also she who kept a meticulous record of Leonid Plyushch's state of health and of the treatments that were destroying him. These reports were then smuggled abroad on samizdats.

Enlargement : Illustration 6

Tatiana Plyushch had to wait 18 months before her first visit to see her husband. In the autumn of 1972 a medical committee gave its verdict: the mathematician was ill with “sluggish schizophrenia”. It was a condition effectively invented by Soviet psychiatrists and one which carried many advantages. There was no need for real symptoms; the “ill” person was declared “incapable”; their trial could thus be held in private and without them being present; and they were inevitably ordered to stay in a special psychiatric hospital for an indefinite period, as they had to wait for a full recovery.

The diagnosis of 'sluggish schizophrenia', established by four of the most eminent Soviet psychiatrists, concluded: “The reformist ideas have remained, becoming inventive ideas in the domain of psychology. Non-critical attitude to his own actions. Represents a social danger.” The prescribed treatment was massive injections of antipsychotic drugs, insulin and sulphur.

In July 1973, after the end of his trial, Leonid Plyushch was locked away in a psychiatric hospital at Dniepropetrovsk – now called Dnipro – in central Ukraine, an institution run by the Ministry of the Interior. He stayed there until just before going into exile on January 8th 1976.

Alongside her four-year legal guerilla warfare, Tatiana Plyushch sent an avalanche of letters to every conceivable Soviet authority, and in particular the KGB. What is striking about these letters today is how free and tough they are in tone. These were not pleading letters but hand to hand combat.

“Yes, my letters were aggressive. I had decided to do it like that. The KGB treated me badly, I replied to them in the same vein. That's all. I was afraid for my children, the key thing was not to show them, not to let them think that they could find any weakness there,” she recalls today.

Once, when she had not had any news of her husband for four months, a KGB officer offered to read her a letter from Leonid. “Listen to this swine reading MY letter?” she says today. She told him: “No, I don't want you to read my letter. If you don't want to give it to me, keep it.”

“You are my husband's torturer,” she wrote to the man who was seen as the father of repressive psychiatry, Andrei Snezhnevsky, director of the Institute of Psychiatry of the USSR Academy of Medical Sciences, a leading figure in the sinister Serbsky Institute and one of those who 'diagnosed' Leonid Plyushch. “What lofty ideals pushed you to act in this way? Hardly the sum of 73 roubles which constitutes the cost of your expert assessment? Where did you develop such a self-satisfied conscience? How did you dare to act in such a way having taken the Hippocratic Oath?”

She wrote to the head of the KGB, Yuri Andropov, criticising the provocative behaviour of local agents. She wrote to Leonid Brezhnev, pointing out to him the many breaches of the law that had been committed. And Tatiana wrote to the psychiatrists in Dniepropetrovsk, urging them to halt the treatments that were wrecking her husband's health. All these letters, which were passed to Soviet intellectual circles and abroad, gave an unprecedented dimension to the Plyushch 'affair'.

The stir caused by these letters served to protect her, as did the enormous international campaign that was set up. At a time when the USSR was negotiating the Helsinki Accords, signed in 1975, which included a high-profile section on human rights, the increase in the number of trials and the Plyushch affair posed serious problems for the Brezhnev regime.

“Tatyana Khodorovitch was informing me in real time, or almost, about the international support campaign. It was of course a very great help,” says Tatiana Plyushch. “And then the attitude of people in Kiev was changing. My children's teachers were nice to them. Once, at the entrance to the hospital, a soldier told me of his disillusionment and explained to me that his wife had threatened to divorce him if he continued to work there!”

Enlargement : Illustration 7

In the winter of 1975 the KGB let it be known they were prepared to allow the Plyushchs go abroad. The couple had to debate the matter, as they had never really previously thought about living in exile. In the end they concluded they had no other choice. At the hospital the shock treatments inflicted on the 'patient' were reduced. Leonid's food also got better and the conditions of his detention relaxed. The 'patient' was even put under a sun lamp to make him look better. On December 30th 1975 the family received their visas to go to Austria.

The final scene took place at Chop in Ukraine, which was then on the border between the USSR and Czechoslovakia and Hungary. It was here that Tatiana Plyushch had to meet her husband, who was being brought from the hospital by the KGB. She waited for some hours before, finally, Leonid arrived, swollen from his treatment and finding it hard to stand up and talk.

“He was wearing a brand-new suit, a tie and even cufflinks! I exploded, tore off this costume and threw the suitcase provided on the ground. I had brought some clothes for Leonid. We redressed him and we got on the train,” says Tatiana Plyushch. On January 11th 1976 the Plyushch family arrived in Paris.

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

- The French version of this article can be read here.

This article is one of a series published by Mediapart this summer about leading Soviet dissidents. Other articles, in French, can be found here.

English version by Michael Streeter