France's role in offering discreet help to the warlord who is now aiming to topple the internationally-recognised government in Libya has been highlighted in an investigation partnered by Mediapart.

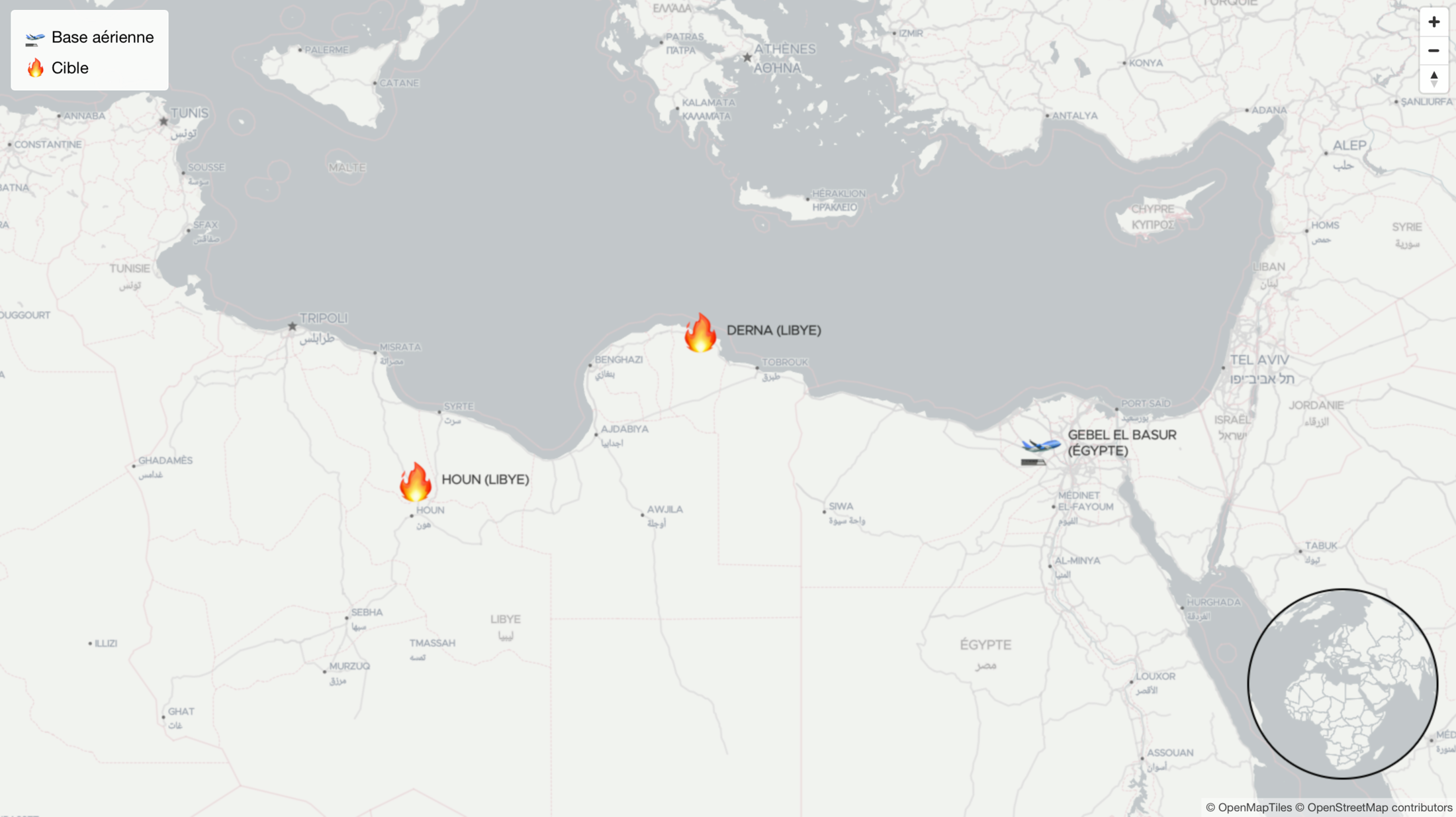

France has been criticised in recent years for what many see as its ambiguous role in the long-running civil war in Libya that followed the demise of Muammar Gaddafi's regime in 2011. Along with the rest of the international community, Paris recognises the Government of National Accord (GNA) under prime minister Fayez al-Sarraj in Tripoli as that country's official government. But it also supports the GNA's main opponent, the self-styled 'Field Marshal' Khalifa Haftar who wields power in the east in the country and who in April 2019 launched an attack on the west of the country, controlled by the Tripoli regime.

Enlargement : Illustration 1

France is even suspected of having – illegally – sent weapons to Haftar's Libyan National Army (LNA). In July 2019 four American-made anti-tank Javelin missiles, which had originally been sold to the French military, were discovered at a base near Tripoli used by General Haftar's Libyan National Army that was retaken by GNA troops. France has formally denied supplying these arms to the LNA.

According to France's defence minister Florence Parly these missiles, which had been for the 'self-protection' of French special forces operating in Libya, were damaged and “unusable” and had been stored in a depot ahead of being destroyed. The French Ministry of Defence did not explain, though, how the weapons were found at a base used by General Haftar's troops.

That is revealed in an investigation which is part of a series of 'French Arms' investigations carried out by the Dutch media outlet Lighthouse Reports in co-operation with online investigative site Disclose, with the support of Mediapart, French-German TV channel Arte, the British online investigative website Bellingcat, and French public broadcaster Radio France (see the boîte noire box below).

These air strikes raise serious legal issues as they were carried out by Egypt in a foreign country in support of an armed group – the LNA – without the authority of the regime which is widely recognised as that country's legitimate government. When Mediapart questioned the French government, prime minister Édouard Philippe's office declined to comment on the issue. Instead it gave a statement insisting that the country's arms sales took place under “strict”, “responsible” and “transparent” controls (see the More tab for their full statement). Dassault Aviation, the French group that makes Rafale jets, did not respond to requests for a comment.

Critics suggest that France is reluctant to harm its relations with Egypt, despite the many human rights violations that have taken place under the rule of strongman Abdel Fattah al-Sisi. Egypt has become one of the French arms industry's biggest customers following the massive 5.2 billion euro contract signed in February 2015 for the purchase of 24 Dassault Rafale fighter-bombers, their weapons – air-to-air and air-to-ground missiles – and a frigate.

This deal was signed in the presence of Egyptian president Abdel Fattah al-Sisi and the French defence minister at the time, Jean-Yves Le Drian, who is now foreign minister. The first Rafale was delivered on July 20th 2015.

Enlargement : Illustration 3

In the months that had led up to the delivery of the first Rafale, Egypt had already been carrying out bombing raids on parts of eastern Libya. They were targeting positions held by the Islamist group the Mujahideen Shura Council, based at the port city of Derna in east Libya, who were accused by Cairo of having been involved in the killing of Coptic Christians in Egypt. Amnesty International said that one raid, on February 16th 2015, killed seven civilians at Derna.

Mediapart understands that the Rafales sold by France first entered action during a three-day bombing raid by the Egyptian air force that began on May 26th 2017. An official Egyptian air force video of the raids shows Rafales taking off from their base at Gebel Al Basur, north-west of Cairo, then landing again after the mission is completed (see below).

Enlargement : Illustration 4

The Egyptian air force said this raid was once again targeting Mujahideen Shura Council “terrorist camps” in the Derna region, in reprisal for a new attack which had killed 29 Coptic Christians and which was blamed on Islamic State.

However, the Derna Mujahideen Shura Council (DMSC) has never been linked to Islamic State. And Egypt has never provided any proof linking the murder of the Coptic Christians to the DMSC, who for their part have denied any involvement.

The information gathered during the course of this investigation shows that the air strikes were in fact more aimed at supporting General Haftar's LNA in its conquest of the east of Libya. A spokesperson for the LNA also told a television channel that the Egyptian raid was carried out with both the co-operation and the involvement of Haftar's air force.

Enlargement : Illustration 5

Mediapart has not been able to establish the precise role of the Rafale jets in the bombing campaign. In the official video the Dassault aircraft were not armed with bombs but with extra fuel tanks and MICA air-to-air missiles (see opposite). This suggests they could have been used to provide air cover for the Egyptian F-16s who carried out the bombing.

The Egyptian newspaper El Watan, citing a news report from the pro-Haftar Libya News Agency (LANA), said the LNA had stated that the Rafales were used to scout for the target sites. Mediapart has not been able to verify this as the laser targeting pod, which is used to identify targets, was not visible under the Rafale's fuselage in the Egyptian air force videos.

In any case the air raid on Derna helped weaken the Derna Mujahideen Shura Council (DMSC), who were battling General Haftar for control of the town. Derna was finally taken by the LNA in February 2019.

A secret raid at Houn against Haftar's enemies

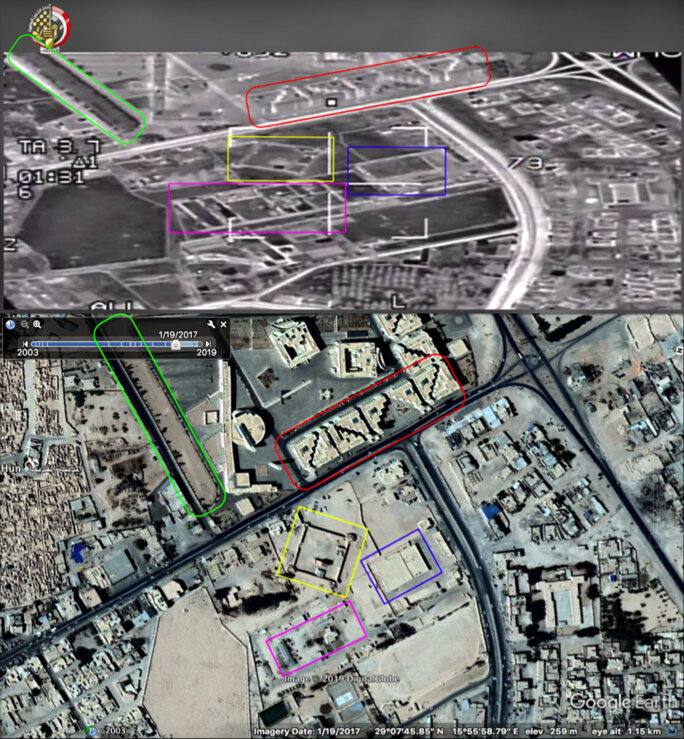

Other information backs up the idea that the bombing raids were designed to help General Haftar. This investigation shows that during the same raid the Egyptian aircraft also bombed the Libyan town of Houn which is 700 kilometres (435 miles) south-west of the official target Derna. That is what we have seen on the images filmed by cameras on the planes, and which have been shown by the Egyptian military.

Enlargement : Illustration 6

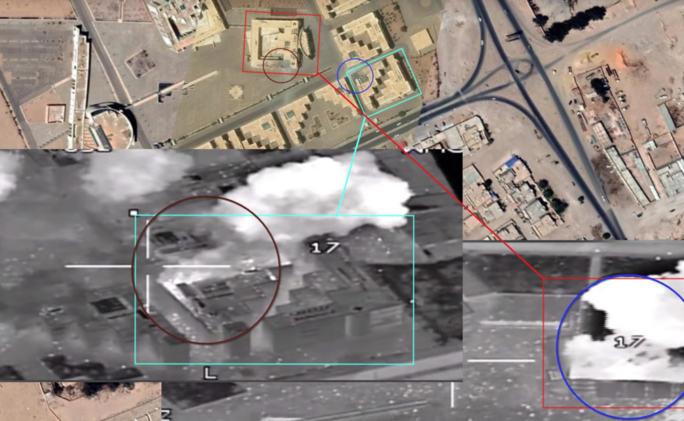

The images provide a brief glimpse of buildings that we have located as being at Houn, which is 300 kilometres (186 miles) south of Syrte. Analysis of satellite images show that several buildings were bombed in the same area and around the date of the raid, between May 20th and 31st 2017 (see below).

Enlargement : Illustration 7

The investigation has also established that some buildings filmed as they exploded were in fact administrative buildings in Houn (see below). Several local media outlets have, with the aid of photos, detailed the damage caused to civilian buildings by the bombing, which has been confirmed by analysis of satellite images.

Enlargement : Illustration 8

Dr Wolfram Lacher, an academic at the German Institute for International and Security Affairs and a specialist in Libyan affairs, told Mediapart that at the time of the raid in May 2017 Houn was held by “local armed groups, forces from Misrata [in north-west Libya] and the Benghazi Defense Brigades, who aren't linked to Islamic State. Some of them even fought against IS at Syrte in 2016”.

At the time, however, the Benghazi Defense Brigades (BDB), an Islamist militia created in 2016, were General Haftar's bitterest enemy. In July 2016 this group killed three agents from France's overseas intelligence agency, the DGSE, when it brought down an LNA helicopter that was carrying them. Then in the spring of 2017 the BDB launched an attack against Haftar's forces in the Libyan oilfields. The general's LNA accused the BDB of having fought alongside the Misrata Brigades in the deadly attack on its base at Brak El-Shati in the south of Libya on May 21st 2017 which killed 141 soldiers.

Enlargement : Illustration 9

German academic Dr Wolfram Lacher said it was “obvious” that the objective of the air strikes launched five days later by the Egyptians on the Houn region, the stronghold of both the Misrata Brigades and the BDB, was to “help Haftar's forces”. He continued: “There was a real opportunity there for him [Haftar] because the Misrata Brigades had started to retreat south towards the Jufra region, where Houn is located, and they had to be forced to leave Jufra as well.” Dr Lacher added: “There were several nights of attacks from May 22nd, and because of these attacks the Misratis ultimately withdrew from the region at the start of June, which allowed Haftar's forces to enter and take control there without any ground fighting.”

The Egyptian air strikes, which took place with French-made Rafales, perfectly highlight how France and its allies such as Egypt and the United Arab Emirates have supported Haftar for years despite his authoritarianism. The support has been justified as being part of the fight against the armed Islamist groups who appeared in the wake of the overthrow of Gaddafi in 2011.

“When I was named head of the DGSE [editor's note in April 2013] Daesh [editor's note, another name for Islamic State] was established in Benghazi,” the organisation's director Bernard Bajolet told Mediapart. “The objective then was to fight terrorism which we did with some results and following some sacrifices. We then forged links with Haftar who was an important player but also with [the official prime minister] Fayez Sarraj,” he said. “I respected this man but he just controlled a very small part of Libya. Haftar, on the other hand, was very effective in the fight against Daesh. Though susceptible to criticism on several issues, he had acquired real influence in Cyrenaica [editor's note, the eastern coastal region of Libya]. I'd now say that these relationships were complementary.”

The relations with Haftar were sufficiently close for military advisors from France's DGSE to be put at the Libyan's disposal. As already mentioned, three of them were killed in 2016 when the LNA helicopter on which they were on board was brought down by enemy fire. And relations were also sufficiently warm that when the French defence minister at the time Jean-Yves Le Drian – now foreign minister – visited Tripoli to see the official government, he also went several times to Benghazi where Haftar was based.

Enlargement : Illustration 10

For France and other allies General Haftar had several attractions. Between his regular troops and militia members he commanded a force of close to 25,000 men, plus tanks, a squadron of helicopters and some ageing Russian fighter jets courtesy of the United Arab Emirates and Egypt. But above all he enjoyed the support of a range of Arab countries, all of them customers and partners of France: Egypt, the United Arab Emirates, Saudi Arabia and Jordan.

On top of this Haftar also has the diplomatic support of Russia and especially the United States. In April, at the start of the general's offensive against Tripoli, US president Donald Trump spoke to the Libyan warlord on the phone and discussed what the White House called their “shared vision for Libya’s transition to a stable, democratic political system”.

US support for Haftar is hardly surprising. Washington supports Egypt's al-Sisi regime and so is not likely to ignore Cairo's most zealous follower in Benghazi.

Moreover, Khalifa Haftar has been groomed for such a role for many years. Before his return to Libya in 2014 to construct the LNA - bringing together former Gaddafi supporters, local militia, tribal fighters and sympathetic Salafists - Haftar spent nearly 30 years in exile in the United States. Here, under the protection of the CIA, he waited for the opportunity to take over from the Libyan leader Muammar Gaddafi. Haftar had gone to the American side ever since, as a Libyan general, he and his troops suffered a humiliating defeat and capture in the Tibesti region of Chad in 1987 and were disavowed by Gaddafi. It was the US who secured his release from Chad and from then on he became an American resource to be used against Gaddafi.

Today, five years after his return to Libya, Haftar hopes to achieve his ultimate goal and rule the country, even though his offensive launched in April seems to have stalled. Supported by Qatar and Turkey, the ruling GNA's forces are holding firm around the capital Tripoli.

Ghassan Salamé, the Head of the United Nations Support Mission in Libya (UNSMIL), who was recently reconfirmed in his post until September 2020, has not given up hope of finding a last-minute negotiated settlement in a conflict that has already claimed the lives of more than 1,000 people and led to more than 6,000 people being wounded since April.

But in a visit earlier in September to the UAE General Haftar's spokesperson, General Ahmed al-Mesmari, said: “The battle is in its final phases … The military solution is the best solution to spread security and reimpose the law.”

-------------------------

If you have information of public interest you would like to pass on to Mediapart for investigation you can contact us at this email address: enquete@mediapart.fr. If you wish to send us documents for our scrutiny via our highly secure platform please go to https://www.frenchleaks.fr/ which is presented in both English and French.

-------------------------

- The French version of this article can be found here.

English version by Michael Streeter