The bad news came quickly in France after last month's European elections. Within 48 hours of the results, no fewer than three different industrial plants in France had announced plans to shed jobs because their businesses here are struggling: power and grid experts Alstom, electrical goods firm Whirlpool, and steel-maker Ascoval.

It is not the first time in France that industrial groups have waited until just after elections were over to announce job losses. Carmakers PSA, which owns Peugeot and Citroën, chose to announce it was closing its Citroën factory at Aulnay north-east of Paris after the 2012 presidential election. But such announcements have never come quite so quickly before.

Enlargement : Illustration 1

It was almost as if the companies could no longer hold off from something which had long been planned but which had been postponed in order not to harm the government. Once the elections were over they were no longer constrained from going public.

On May 28th the American group GE, which had bought French firm Alstom's power and grid business in 2015, announced the loss of 1,044 jobs in France. Unions fear this announcement is the precursor to the possible closure of the firm's operations in Belfort in the east of the country. On the same day the company which had taken over electrical foods firm Whirlpool's operations at Amiens in northern France – a deal that Emmanuel Macron himself has taken a personal interest in – announced that the factory was going into administration because of a lack of business. On that same day, and widely ignored in the media, came the news that workers at the former gas exploration and production unit of French energy giant Engie, which had been bought by Neptune Energy, a venture backed by private equity firms Carlyle and CVC Capital Partners, were to lose their jobs. Over the last two years the business has been moved to London and the announcement last month confirmed that the remaining 113 staff in France were also to be made redundant.

Meanwhile, on the very day that they were supposed to be taken over by British Steel – with the support of the French authorities - workers at the Ascoval steelworks at Saint-Saulve in northern France learnt that the owners of the British company, private equity firm Greybull Campbell, had announced that the business was going into liquidation. On top of these announcements came news of the closure of the Ford factory at Bordeaux in south-west France, a closure the staff are challenging in court, the closure of the Arjowiggins paper mill by its main shareholder Sequana on the grounds it is not profitable enough, the loss of some temporary jobs at the Fonderies du Poitou foundry in west France and a hundred or so smaller job losses which did not gain wider attention.

This, then, is the state of French industry today. What should be a wealth-creating sector is now an urban wasteland. After Luxembourg, Cyprus, Greece and Malta, France has the weakest industrial sector in the European Union in relation to its overall GDP. Industry now represents just 11% of economic activity in France, compared with 23% in Germany and 15% in Italy. “France has an undersized productive function in relation to its economy,” says Louis Gallois, the former chairman of the European aircraft manufacturer Airbus. It is this which impoverishes France and means the country runs a permanent trade deficit, something to which the government appears indifferent.

For in the aftermath of this stream of redundancy announcements the government did not sound the alarm or raise questions about the best way of reversing this industrial trend. Its supply-side economics, based on a reduction in the cost of employing staff and a reduction in social benefits, is supposed to be the answer to everything: to de-industrialisation, to the internal disequilibrium caused by the euro, to the problem of upgrading French industry, to the lack of innovation and creativity, to the absence of collaboration and co-operation within the sector, to the shortcomings of some company executives, to the excessive role of finance within industry and so on.

Enlargement : Illustration 2

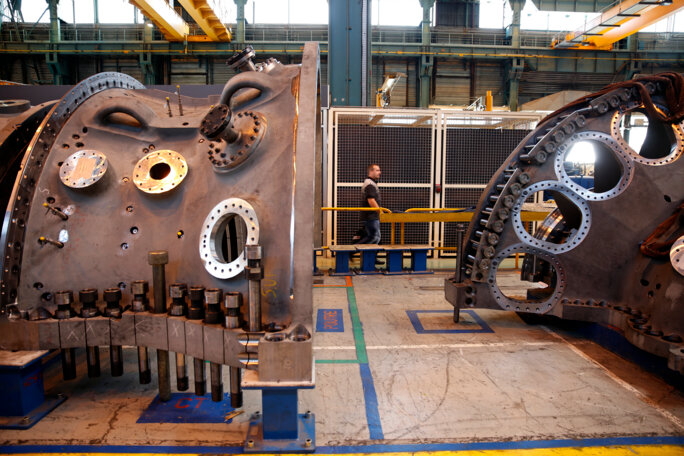

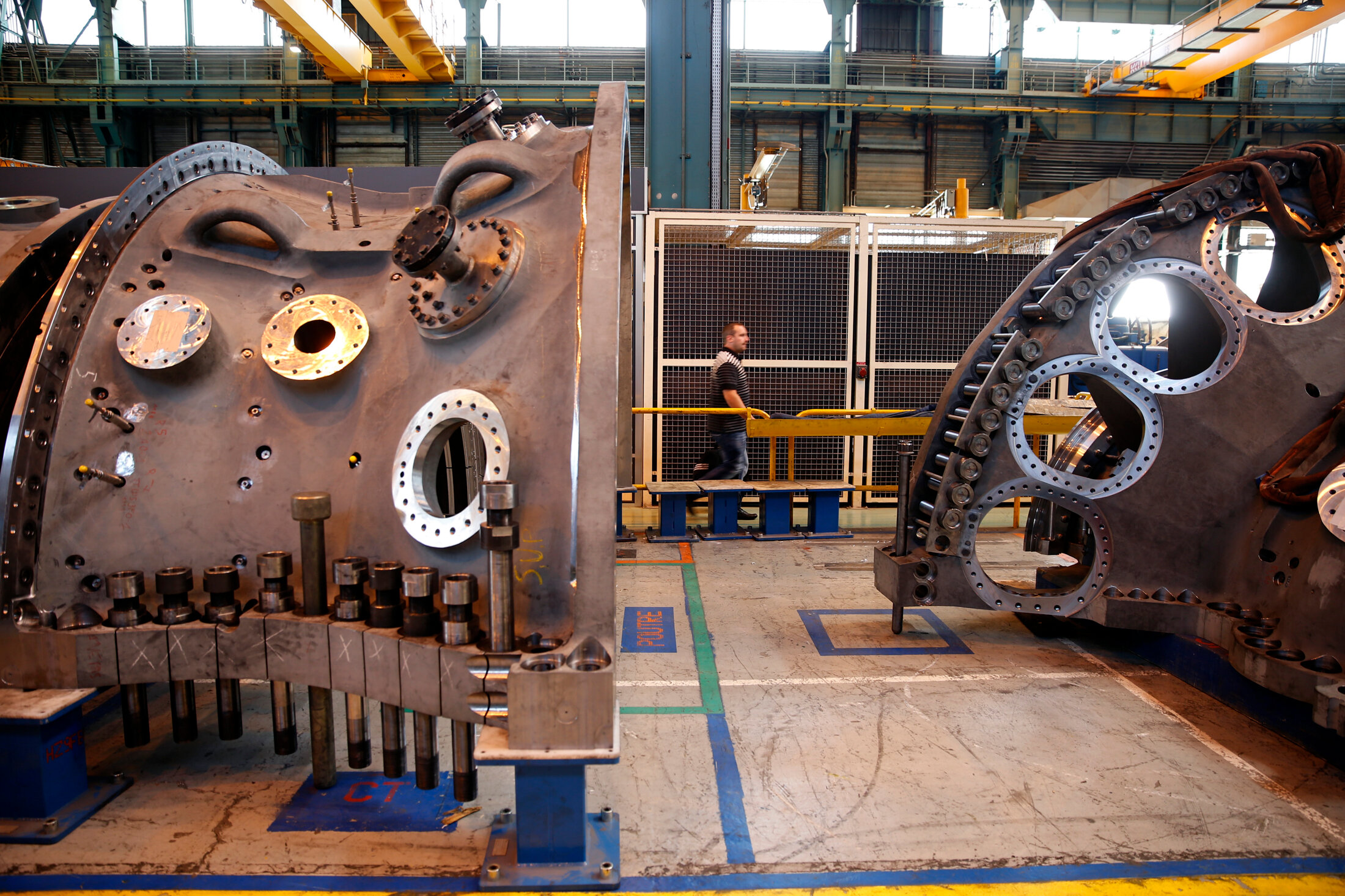

After the job losses became public, the government's only concern was to get itself off the hook, in particular defending itself against claims that it had been informed in advance by the American group GE about their redundancy plans. “We were no more aware than the people affected,” the junior minister Agnès Pannier-Runacher told public broadcaster France Info. The government's official spokesperson, Sibeth Ndiaye, repeated the denial and said that GE's problems at Belfort in France - where they make gas turbines - was a fallout from the transition to new forms of energy (read the unions' response to this, in French, here). In fact, many of the production work at Belfort has been transferred to the United States, something that employees and experts warned would happen when GE announced it was buying part of Alstom.

Even though the government has employed lies for some time as part of its communication approach, this kind of defence of its actions only serves to further devalue the currency of public utterances by the state. It also shows how much the government values public opinion and adds insult to injury by taking us all for idiots. “I hope that the president of the Republic and the government will show the same energy in creating new jobs in Belfort as they did in postponing the announcement of the redundancies until after the European elections,” said the mayor of Belfort, Damien Meslot, from the conservative Les Républicains.

How can one really believe that the French government was unaware of what was going on at Alstom? The president, Emmanuel Macron, has been involved in the case since the autumn of 2012 when he was the deputy chief of staff to President François Hollande at the Élysée. It was he who, behind the government's back, negotiated the takeover by GE. And he who, as a minister, later strove to pull to pieces one of the rare measures of protectionism that his predecessor as minister for the economy, Arnaud Montebourg, had wanted to implement to afford some safeguards for the energy branch of Alston in any takeover - precisely to avoid such activity leaving France altogether.

Moreover, GE knows just how to navigate its way inside France's public administration and the circles of power in order to make its voice heard. To help its takeover negotiations the American group had hired Claude Gaymard, former president of the overseas investment agency the Agence Française pour les Investissements Internationaux. Gaymard quit the group just after the sale was completed.

Then in April 2019 GE appointed Hugh Bailey, Macron's former industrial advisor at the Ministry for the Economy, who helped negotiate the takeover, as director general of General Electric France. This appointment - impossible in other countries which respect the minimal requirements for ethical rules – says a great deal about GE's intentions in France: to gain access to the highest levels of power and to be able to negotiate as it wants.

Since Jeff Immelt left the helm of GE in 2017 his successors, John Flannery and then Lawrence Culp, have made clear their dislike of the Alstom purchase, with Flannery describing it as “very disappointing”. The sale was partially responsible for the US firm making a 23 billion dollar “write-down” in its power division, which has led to an investigation by the US Securities and Exchange Commission. Even if the French government had not been in direct contract with GE, this kind of public information should have set alarm bells ringing and started them looking at ways to find other substitute businesses for the site or compensation for the workers. Instead the government did nothing.

The French presidency's words devalued

Yet in fact the government clearly did receive direct information from GE. On May 22nd 2019 the minister for the economy and finance, Bruno Le Maire, effectively became GE's spokesperson. Before the redundancy plan was even announced, and in response to concern from local union officials who feared redundancies were indeed on their way, the minister told the National Assembly that some restructuring at the plant was inevitable. Two days later, political leaders from Belfort went to the Élysée to discuss the situation at GE. Yet the government still insists it knew nothing.

The same ruse was used in relation to the former Whirlpool factory at Amiens. This, too, was a symbolic issue for Emmanuel Macron's presidency. Having visited the factory between the two rounds of the presidential election in 2017, Macron returned there in October of that year promising to do all he could to help it find a buyer. A local buyer, Nicolas Decayeux, came forward and the French authorities agreed to help him with 2.5 million euros and Whirlpool with 7.5 million euros to resume production on the site. These sums were completely insufficient for the resumption of industrial activity at the site. Indeed, it was more like the kind of money that would be offered to help fund a large company's redundancy plan, to extend it over time and reduce the costs.

And, in fact, that is exactly what happened. From the beginning of 2019 the staff at WN – the new name for the factory at Amiens – were alarmed at the fact that the company had practically no new business, as Mediapart stated at the time. When questioned about this on April 18th, the chief of staff at the local state prefect's office assured Mediapart that everything was going as planned. Yet the very next day an emergency meeting was called at the Ministry for the Economy and Finance to discuss the issue, resulting in a report which established the need for a “profound restructuring of the business”. This assessment of failure was postponed a month and a half, until after the European elections had passed.

The same three-card trick was carried out in relation to Ascoval. Numerous investigations have highlighted the duplicity of state services in preventing the takeover of the steelworks, which were plunged into difficulty by the problems faced by their owner Vallourec. The French state investment fund the Banque Publique d'Investissement (BPI) agreed to help Vallourec but not Ascoval. But under pressure the French government was ultimately obliged to reopen the case. On May 2nd 2019 a court at Strasbourg approved the plan for British Steel to take over the steelworks at Saint-Saulve. But then less than three weeks later, on May 21st, the British group was itself put into liquidation.

Today the French government makes out that only now is it finding out about British Steel's problems and the reputation of its main shareholder, private equity firm Greybull Capital. Yet there have been a number of articles in the British press about the problems faced by the steel-maker since it was sold by the Indian group Tata and about the practices of its new owner, which behaves more like an asset stripper than an investor (read articles here, here and here).

As for the Ford factory in Bordeaux, the French government did not even try to get involved. The car-maker was opposed to finding a new buyer and the authorities did not stand in its way. Without any support for its plans, the potential Belgian buyer, Punch, threw in the towel on May 29th.

After a change in the law on redundancy plans by the current government – meaning that only a group's business activity in France is to be taken into account when assessing a redundancy plan and not in the rest of the world – multinationals now have a guarantee that they can make staff redundant and close factories at low cost. This process has been further helped by the fact that, thanks to other recent reforms in France, the opportunities for staff to oppose such measures at industrial tribunals has been seriously restricted and the level of compensation they can receive has been capped too.

Until quite recently the employees of a factory that was in difficulty still retained some hope when a president or the authorities became involved; but today they no longer expect anything. Past examples involving the Gandrange steel plant, the Florange steel furnaces and now Alstom and Whirlpool have all involved promises of support from the top. Political commitments are now seen for what they are: a distraction to pull the wool over people's eyes. Bruno Le Maire's visit to Belfort on Monday June 3rd was unlikely to change employees' bleak assessment.

“Everyone believed it, wanted to believe it,” said Frédéric Chantrelle, a former representative of the CFDT trade union at Whirlpool. “The president came just after he was elected, we told ourselves 'it's going to work'. But Macron the great entrepreneur, who sold us a plan, we now see where that ends up....So he is the third president who has come to an industrial site to say that it will be saved, and then it hasn't worked. In the end these presidents are not a great advertisement....”

That has not stopped the minister of finances, Bruno Le Maire, from crowing about the government's actions. “Over the last two years, three out of every four threatened industrial jobs in cases dealt with by the Ministry of the Economy and Finance have been saved,” he said in February in an interview with the business newspaper Les Échos. He went on to say that thanks to its policies the government had succeeded in “stabilising industrial employment”.

The French state started planning and arranging its own impotence in the industrial domain (read in French here) some years ago. Not only did it abandon having an industrial policy – it even got rid of the ministry responsible – the state also removed all direct and indirect support for industry. All those tools that could have had a beneficial effect, created momentum and allowed for the creation of industrial ecosystems - funding methods, state orders, research policies, monitoring and controlling dominant positions – were taken away. Nothing was done to encourage different industries to co-operate and to upgrade.

Intentional destruction

However, under Emmanuel Macron things have taken a turn for the worse. It is no longer a matter of deliberate impotence, letting free and unfettered competition or the laws of the market run their course. It is now about intentional, organised destruction, abandoning whole sectors to the rapacious, predatory nature of finance.

For when it comes to such matters Emmanuel Macron has serious form. Ever since 2012, in every post he has occupied, Macron has worked to reduce industrial support systems in France, to indulge in a Monopoly-style devastation of industry, setting himself up as a merchant banker as head of state. As far as he is concerned a business is simply something to make money from, a structure from which one has to extract the value as quickly as possible.

Alstom is set to come back to haunt this presidency for some time, but there are also many other examples of this kind of deal that Emmanuel Macron has wanted and which, by chance, have gone against French interests, even when the French positions in those cases were in fact the strongest ones. This is not about extolling the virtues of some Franco-centric nationalism. But when every major deal ends up by systemically stripping industrial activity from France, that is a good reason to sit up and take note.

For the capitalist rule is simple and everyone plays by it, even if the French government seeks to deny that by hiding behind grand phrases such as world or European market leaders; and that rule is that the winner, the strongest, takes it all, the headquarters, the business activities, the research and development, the jobs, leaving just the scraps behind.

It was in this way that Emmanuel Macron, then deputy chief of staff at the Élysée, oversaw the loss of the French state's control of aircraft manufacturer Airbus. As part of an agreement with partners Germany, France agreed to reduce its share from 30% to 15% so that both countries would have the same stake in it. As the rules had changed, and Airbus was becoming more like a normal company, France could at that point have demanded as compensation a review of the national agreements over where aircraft were produced. But instead Germany continued to benefit from the existing agreements which allowed it to produce most of the A320s, the group's most successful aircraft.

The result is that while the factory in Hamburg is hiring staff fast to keep up with the demand for orders for the A320, the plant in Toulouse in south-west France which makes the A380 is starting to shut down some production lines. This does not just threaten thousands of jobs both directly and indirectly through sub-contactors, it also risks the ability to carry out research and innovation.

The example of Technip is even more spectacular. The world leader in project management, construction and engineering for the oil and gas industry, the French group was absorbed by an American company four times smaller as part of a marriage between 'equals' based on manipulated stock market prices (see story on background to this here). The French state raised no objections. Two years later the group's main activities – 80% of the turnover is based on Technip's former business – have moved to Houston and London.

All the well-known governance rules which were supposed to keep a balance between France and the United States in relation to the business went up in smoke with the departure of Technip's former CEO Thierry Pilenko, accompanied by a fat cheque. Everything then came under American control. The major suppliers for Technip included Vallourec and Ascoval.

The shipbuilders at Saint-Nazaire on the west coast of France, which were nationalised in a hurry in July 2017, have also been affected. Though it has kept the French stake in the business at 50% the government is planning to hand operational control to the Italian group Fincantieri. What happens next is quite easy to forecast: at the first sign of difficulty the business will be repatriated into the Italian shipyards and the French state will simply be left paying the export credits that are indispensable for some customers, starting with the shipping line MSC, a group which is so dear to the Élysée - as Mediapart has charted.

A similar fate could have befallen Alstom's railway business if the European Commission had not vetoed its planned merger with Siemens; everything would have come under German control. Other possible such mergers are still on the horizon: for example there are plans for France's Naval Gorup and the Italian Fincantieri to merge, a move that would be likely to benefit the latter.

Now, too, there is the proposed merger between carmakers Fiat and Renault, announced just before the European elections, which will benefit the Agnelli family, who would become the major shareholder with a 15% stake. The French state's share would be cut by half leaving it without financial compensation or power. There are more and more doubts being raised about a deal which seems so unfavourable to Renault. To comply with stock exchange rules the deal is based on Renault's share value which has tumbled by a half since the arrest of Renault's former chairman and CEO Carlos Ghosn in Japan. The group's 19 billion euro capitalisation corresponds to the 43% stake that Renault has in Nissan and the group's liquid assets.

In other words, Renault is not worth anything. Its factories, market share and its considerable advances in electric engines – an area Fiat which has not got involved in - and its research are effectively valued at zero. “How can Renault management endorse a deal at that price?” asked one commentator on Bloomberg News.

So the impression the government gives from its policies is that French industry is worth nothing. It can be sold off, squandered or handed over to The Beagle Boys of the world of finance with no problem. Everything should be left to “creative destruction” to use a phrase associated with Austrian economist Joseph Schumpeter and advocated by a French government that supports pseudo-Darwinian economics.

The problem is that while we can all view the destruction we cannot see much creation. That is for a very simple reason: you don't build in a desert (see Mediapart's map of the industrial disaster around the city of Amiens). Capitalism is not just based on the accumulation of capital but also the accumulation of means, skills, knowledge. It is on this that innovation and the future relies. It is a trend that can be seen right across the euro zone as well as in France; the most dynamic cities and countries, which already host most business activity, are those that attract services with high added value, new business activities or future developments.

The government can talk about environmental transition, the digital world and artificial intelligence but if it allows the skill base to be destroyed, or even takes part in that destruction, then all those activities will take place elsewhere. A few grand dinners at the Palace of Versailles with Silicon Valley billionaires are not going to reverse that trend.

Emmanuel Macron is aware of these realities. So why is he pursuing these policies? Who will they benefit? The de-industrialisation of France has reached such a critical point that the country runs the risk of being dragged backwards and into austerity for ever, harming its future. Is that his plan?

------------------------------------------------------------------------------

The French version of this article can be found here.

English version by Michael Streeter