Mediapart has become used to getting its share of criticism after almost every one of its political investigations. But this summer the public relations offensive carried out by François de Rugy, helpfully relayed by friends in the media, is unusual in having taken place after his resignation as environment minister on July 16th 2019 following revelations by Mediapart. The aim of the former number two in the government – who reverted back to being an MP when he quit as a minister – is clearly to restore his image and keep alive his political future.

Mediapart had reported how François de Rugy and his wife Séverine regularly organised grand dinner parties with fine wines and food provided for by the public purse, while also ordering the redecoration of their ministerial grace and favour apartment at a cost of more than 60,000 euros - also paid for by public funds. Questions were also raised over his use of his expenses as an MP to pay political party subscriptions.

Mediapart has not responded to every article in this media campaign. This is because the arguments put forward have often seemed derisory, inappropriate or dishonest. Supposedly definitive demonstrations of his case have been based on incomplete or erroneous information. Most of the time this was because the media who published François de Rugy's defence were happy to take his word for it; so it was the former minister and former president of the National Assembly who chose what documents he wanted to pass on.

We thought that not many people would be convinced. And Mediapart preferred to carry on investigating other subjects rather than spend time justifying the work we have done. When asked by other media we have simply explained that we do not withdraw a line of what we have written.

However, we are not naïve either. When you conduct a press campaign, when you appear on the main evening TV news bulletin on public broadcaster France 2 in front of millions of viewers without being asked a single tough question, when you carry out lots of interviews on the major radio stations and trigger press articles that sometimes resemble press releases, then you end up sowing confusion.

François de Rugy has certainly not managed to transform the 'Rugy affair' into the 'Mediapart affair' as he wanted to, but nonetheless he has managed to instil some doubts. We have heard them this summer about various aspects of our investigation, about both the style and the substance, particularly among people who do not read us. That is the reason behind this article which is not behind the paywall. That way everyone can come to a view about the facts, and the facts alone.

“Should François de Rugy really have resigned?” has been the insistent refrain of a section of the media (including in this interview on France Info radio). It is as if we were guilty of an injustice, as if we had made too much of it, as if we were responsible for his acts.

Let us first state something pretty obvious: we just did our job, which involves publishing facts when they are established and in the public interest. We do not control the consequences of revealing these facts. We never wrote an editorial demanding that François de Rugy had to resign and even had we done so that certainly would not have led to his departure from the government.

On the other hand, the minister himself and those who had nominated him as a minister took the view that given the information revealed and the impact it had, François de Rugy could no longer stay in his post.

Enlargement : Illustration 2

Why criticise us for the effect that our revelations had? Is it our fault if François de Rugy's behaviour caused outrage? Do you have to be blind not to understand that dissipating public money on friends is profoundly shocking? And even more so when the person in the firing line belongs to a government that was elected against the backdrop of the Fillon affair – which involved claims that right-wing candidate François Fillon misused public money – and which stood for bringing a sense of morality to public life and overhauling old customs and practices? What is more, the politician concerned, François de Rugy, made his political name over the years by calling precisely for greater transparency in MPs' expenses.

The strangest part of this saga is that the very same people who spent whole days detailing and dissecting our stories are now complaining that they have been given too much prominence in public debate.

It it certainly true that the role of a newspaper such as Mediapart is to rank information and news in order of importance. And of course the Rugy affair does not have the same importance as other cases that we have revealed in the past; for example, a presidential campaign funded by a dictator (the Sarkozy-Gaddafi affair). Or, on the question of personal excesses, a budget minister with a Swiss bank account (the Cahuzac affair).

Nonetheless, the Rugy affair is not a trivial issue. Indeed, it is highly symbolic. As we have written, it was made possible by the lack of control over MPs' expenses. For the past eleven years, ever since Mediapart was set up, we have explained that this system can only lead to excesses, abuses and thus scandals. But no measures has been brought in that match the scale and importance of the issue.

As long as this situation remains there will be more such affairs. And politicians will continue to complain or explain – adopting the well-worn excuse of those who have nothing else to say – that others have done the same or worse in the past.

A “manhunt”? No. “Relentless”? Yes, we happily accept that. But only in the sense of a relentless wish to document the failures in the oversight of our elected representatives' expenses.

Just to spare a man, should we have kept quiet about the fact that when de Rugy was president of the National Assembly he entertained his friends with the finest wines and dishes at the taxpayers' expense? Should one have stayed silent about the exorbitant cost of work carried out to his grace and favour apartment, paid for out of the public purse? Or not revealed his social housing-style accommodation near his home city of Nantes that was kept on even though he had been living in Paris for several years on a big salary? Or the abundant use he made of government drivers and cars or the way he misused his Parliamentary expenses as an MP? Not to have published these issues would have been to have abandoned journalism, and would have been a major mistake not just some minor slip-up.

Then we were accused of turning the revelations into a “soap opera” by not publishing all our information in one go. We have little time for this point of view. Our articles are already long because they are detailed and referenced: we cannot put everything, on different issues, in the same article. When we have lots of information we publish it, day after day, whenever the articles are ready.

In this case, we had certain information at the start, about which we questioned François de Rugy: the dinners at the National Assembly and the work on his grace and favour apartment at the Ministry of the Environment. This was the basis of two articles. Then other information turned up and other lines of enquiry came to fruition because certain people were shocked by the minister's responses and either sent us or confirmed information. Today, as in many ongoing cases, we are still looking to verify facts that might or might not give rise to new revelations.

We questioned François de Rugy during the course of these investigations and then published the articles, which always included his replies. This is what journalists do all around the world; to criticise this as 'Mediapart's methods' is thus absurd.

We have also been criticised for using photographs of lobsters and bottles of wine. Apparently this is rabble-rousing and “mixing emotions and facts”. This kind of criticism is irritating, and not just because photography is part of the culture of the world of journalism.

It is also irritating because critics are never happy whatever type of document we publish. A photo? “We're at the mercy of the Stasi.” An email? “You're breaching the confidentiality of correspondence.” A compromising audio recording? “It's a breach of privacy.” A contract in an article on corruption? “You're flouting business confidentiality.”

However, if one fails to publish any document, and base the story on, for example, a series of corroborating comments from witnesses, then the counter-attack is almost more violent. “Where's the proof?” critics cry.

This is how the trap is set: whatever the nature of our investigation, whatever the material it is based on, it is how our investigations are carried out which then becomes the sole issue for discussion, eclipsing the content of the affair itself. “How did you get that information ...We'd give these names if we had them, and we are going to get them,” the editor of a major press group threatened us, as he called on us to reveal our sources live on a TV news station.

Some people have suggested on social media that the photos were not genuine. This recalls the time that the budget minister Jérôme Cahuzac tried to claim that the voice on the recording that Mediapart had revealed details about was not his – the legal system proved him wrong. Or when Nicolas Sarkozy sought to claim that the Libyan document about funding of his 2007 presidential campaign was a forgery (again, the courts proved otherwise).

François de Rugy and his wife Séverine Servat de Rugy did not dare to go down that route. But unsure of what else to come up with, they complained about the tone of voice that we used on the phone. A far-right magazine then came to the couple's aid by referring to the lack of time they apparently had to respond to our questions. No one bothered to check the truth of this claim with Mediapart. Yet we could happily have shown them some text messages in which Rugy's director of communications thanked Mediapart for our patience.

We are always careful to give sufficient time to people who are the subject of allegations to respond. This is out of intellectual honesty but also because if we do not, we could be convicted in any subsequent legal action for defamation. François de Rugy has himself announced that he is taking legal action against Mediapart; on September 3 the former minister started proceedings for defamation relating to one of our articles, which concerned his social housing-style accommodation.

We are not daft. Nothing will convince those who do not want to be convinced. But for those who, in good faith, have doubts about some of the confirmation we have published here are our explanations on the key issues of this case.

Was François de Rugy “cleared” over the issue of the dinners at the National Assembly?

This was what kicked off the affair: the dinners paid for with public money held at the president of the Assembly's official residence, the Hôtel Lassay. De Rugy has said and has repeated over the summer that he has been “cleared” over the claim that he squandered taxpayers' money for personal, private dinners, and that Mediapart's revelations had been “refuted” over it.

On July 29th the former environment minister solemnly declared on news channel BFM TV that the report by the National Assembly into the revelations had “said in black and white that the dinners at the Assembly were working dinners which were within the terms of me carrying out my duties.” He had also told France 2 television on July 23rd: “All the dinners about which Mediapart had attacked me were dinners which were inside the terms of my duties at the National Assembly”

That is quite simply false. Though it was very lenient, having been conducted by his former subordinate, the National Assembly report nonetheless criticised three of the 12 dinners that had been queried: the Christmas meal in 2017, the Saint Valentine's meal in 2018 and a third dinner with no “discussion theme”. The report pointed the finger at the “familial or friendly character” of these dinners and their “excessive” cost. Incidentally, François de Rugy later agreed to reimburse the money involved.

The former minister was particularly ill at ease when it came to defending himself over the Saint Valentine's dinner in 2018 which was paid for by the taxpayer. This led him to state a fresh lie on BFM TV when he claimed he had dined at the Assembly on that evening because he was between two Parliamentary sittings, in “the afternoon and the evening”. But as the news agency AFP has shown, this was not true. On February 14th 2018 the sitting ended at 7.20pm and he had left his official seat at 4.10pm, according to the official minutes of the sitting.

What of the nine other dinners about which questions were raised? The National Assembly report considered that they did not pose “a particular problem” and could not be classified as “private” events. Our investigations showed precisely the opposite. Photos of the evenings, profiles of the guests, statements from those who took part, the admissions of Séverine de Rugy herself: all our information shows that contrary to the statements by the couple, not only was there neither a “theme” to these evenings or any report on them, they in fact involved a “circle of friends”.

Several participants at these dinners questioned by Mediapart acknowledged that they were acquaintances of the ex-minister's wife (see our stories here and here). Séverine de Rugy herself declared on her own Facebook account (then in Le Point and Paris Match magazines), that the photos of the dinners published by Mediapart came from “friends” who were present, involving friendships “more than 15 years old”.

How does discussing traffic circulation in Paris with the boss of the hotel Les Bains Douches or immigration with a journalist from the television magazine Télématin come under the job description of the president of the National Assembly?

What is more, the broadcast commentator Jean-Michel Aphatie, whose wife is a friend of Séverine de Rugy, has confirmed that he was present at one of these dinners and has said several times that it was not a work event.

The new president of the National Assembly, Richard Ferrand, is meanwhile aware of the problematic nature of these dinners: after the report on the Rugy affair, Ferrand announced the setting up of a working group to reinforce the “rules and procedures of the [Assembly] presidency”.

Was the work he had carried out at his ministry justified?

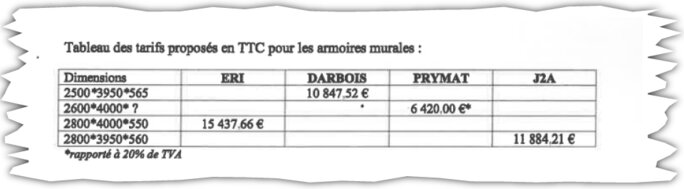

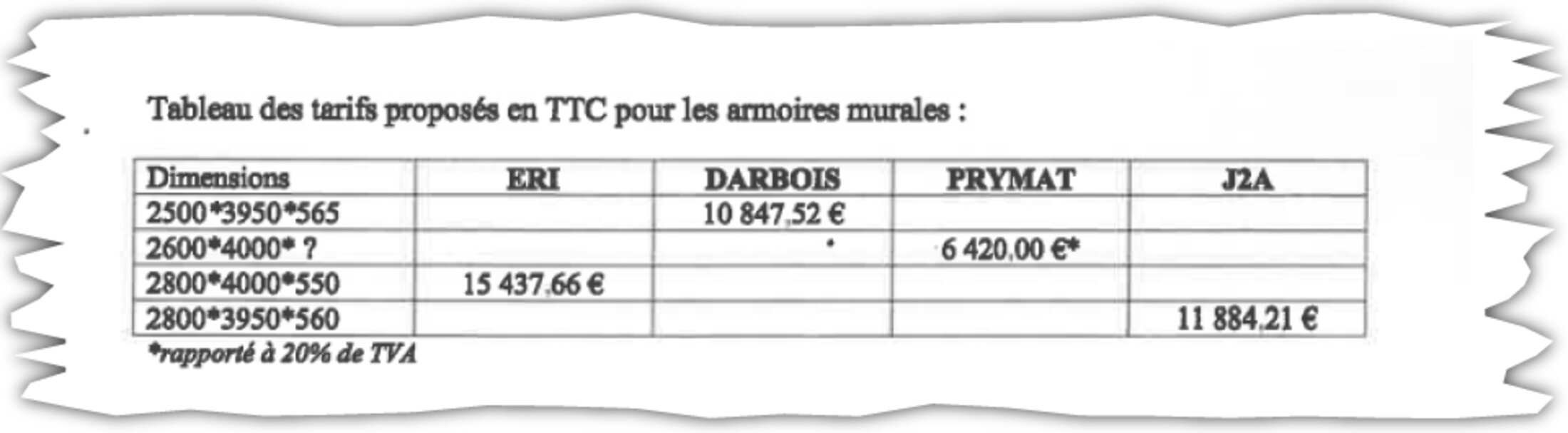

At the end of 2018 François de Rugy ordered work to be carried out at his grace and favour apartment at the Ministry of the Environment at a cost to the taxpayer of 65,000 euros. The flat was repainted, there were new carpets and floors, the bathrooms were refurbished and storage units were installed at a cost of 17,000, as Mediapart revealed.

On July 23rd 2019, after the publication of the administrative investigation carried out by the prime minister's office into the renovation work, the minister trumpeted on France 2 television that he had been “cleared”. That is factually incorrect.

While the report said that “the rules of public sector orders have been respected overall” - something that Mediapart never disputed – it highlights in black and white how some services cost too much because of the “choice of finishes” made by the minister. This was the case with the giant walk-in wardrobe (which cost 15,437 euros) and the painting of the moulding, which at 16,261 euros the report described as “very high”.

In relation to the wardrobe the report said its high cost was due to the “quality of the materials used” and to the layout which was “made to measure”. The report's author was astonished that the order for the work was made with “relative urgency” and took the view that the bill could have been lower had they opted for a slightly “lesser” finish. The report also confirms that out of the four people who tendered for the wardrobe work, the one who was chosen was far more expensive; more than twice the cost of the lowest offer:

Enlargement : Illustration 3

And as for the other work carried out, only in the case of the flooring was the cheapest offer chosen.

The report goes even further. It reveals that some of the work ordered by François de Rugy was either rejected by the Ministry's works team or had to be reduced in cost. This was the case with the curtains and with parts of the made-to-measure storage space and decoration in the main bedroom, the living room and the bathrooms.

To justify this major expenditure in an apartment which is occupied on a short-term basis, François de Rugy put forward two arguments. One was the “wear and tear” of the apartment. The report by the prime minister's office referred to this, explaining that the “relative state of wear and tear” of the surfaces in “some rooms” … could justify work being carried out”. But this argument had doubts cast on it by one artisan involved in the work to whom Mediapart spoke, and by the photos of the flat that we published.

Then the ministry came up with another argument; the need for storage space in an apartment occupied by five people. “They [editor's note, the Ministry of the Environment staff interviewed] also highlight the lack of storage capacity in this type of old accommodation, while the new minister's family is made up of five people,” says the report into the issue, which also notes that the couple only had the children there “occasionally”.

This statement was passed on by most of the media in their coverage. Yet it is not true. According to our information, the two children from the minister's first marriage – who are looked after by their mother – hardly ever came to Paris. The walk-in wardrobe was, then, essentially for the use of François and Séverine de Rugy.

Curiously, the report from the prime minister's office did not give a view on whether François de Rugy had respected the circular from prime minister Édouard Philippe on May 24th 2017 which called for “limiting the use of public money strictly to the carrying out of ministerial functions”.

But the prime minister himself realised that there was a problem because, at the end of July 2019, he decided to send out a new circular setting out rules on work carried out on grace and favour accommodation. From now on ministers must now get prior permission from the prime minister's office for any works costing more than 20,000 euros.

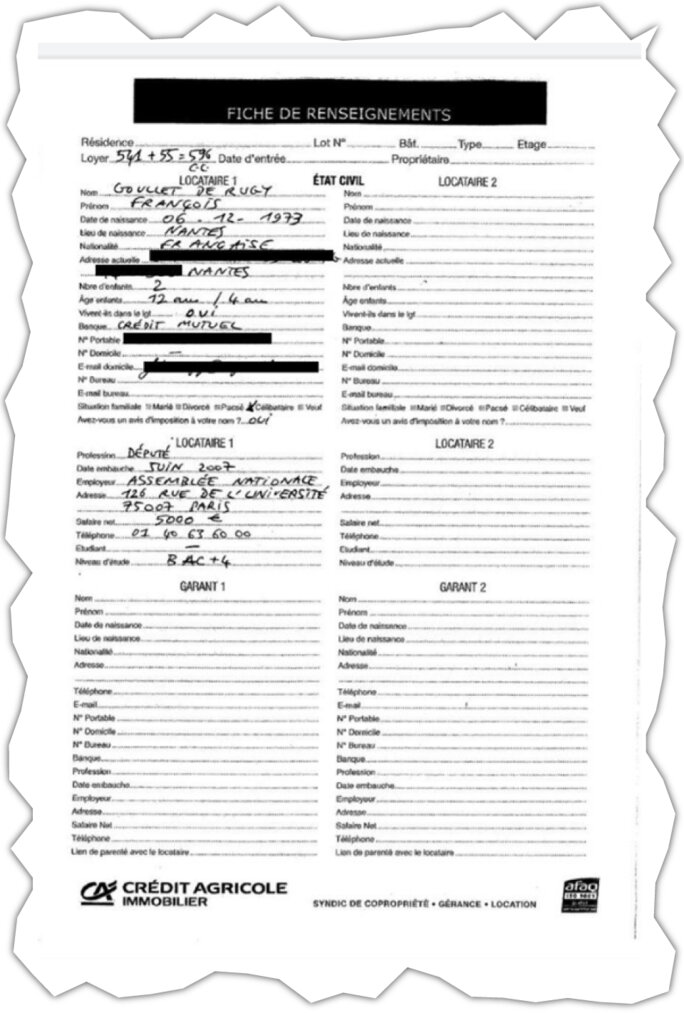

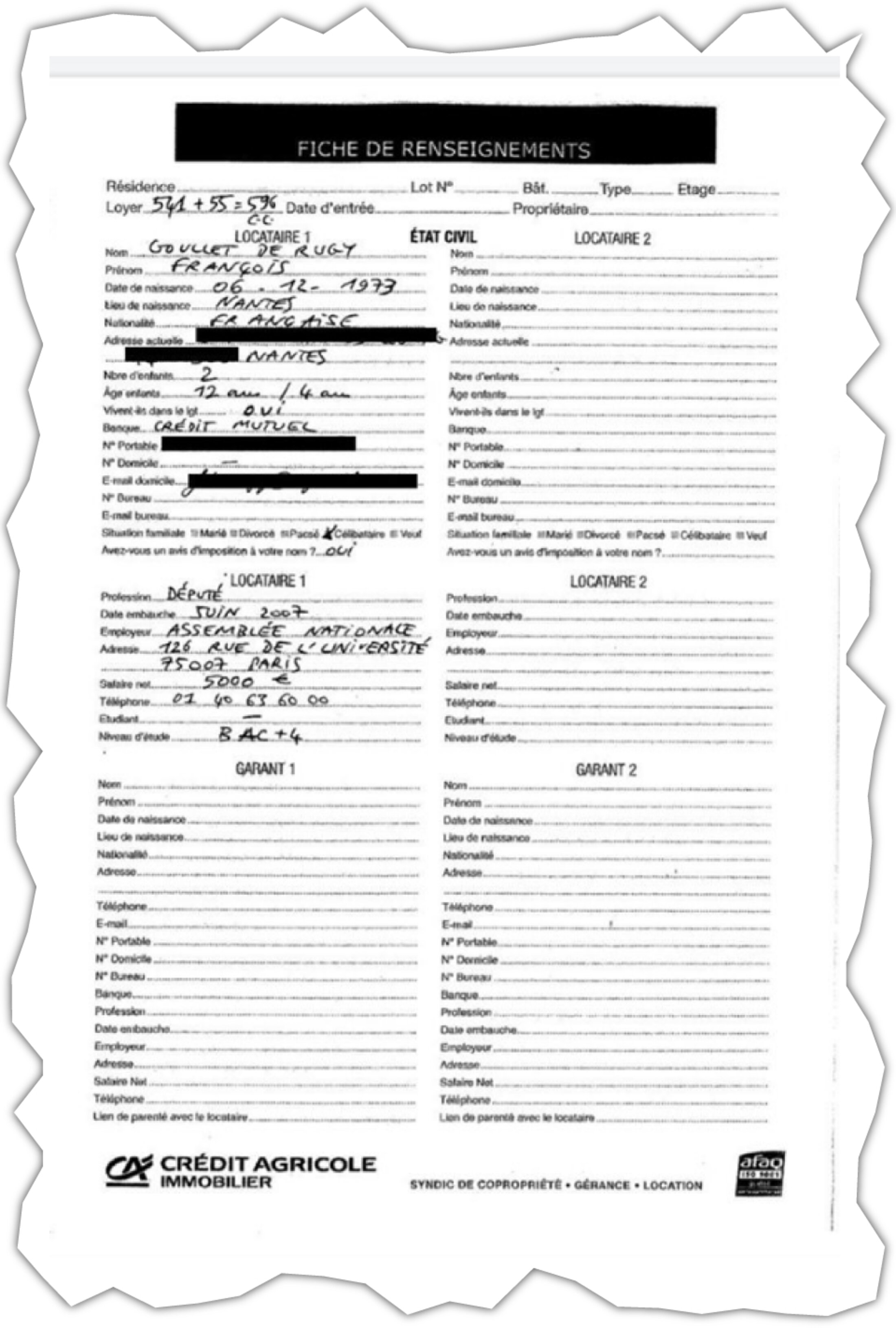

Was it appropriate for de Rugy to have social housing-style accommodation near Nantes?

“François de Rugy also benefited from social-style housing.” That was the factual headline of our article which appeared on July 11th. And contrary to what de Rugy wanted everyone to believe, it is true. Or more accurately it was true, because we understand that the former minister was due to leave the accommodation concerned some time this month, having given notice at the start of August.

The day before our article appeared François de Rugy sacked his chief of staff. This followed an earlier article by Mediapart, published just a few hours before, in which we revealed she had benefited from social housing – known in French as HLM – in Paris for 18 years. And that she had kept on this lower-rent accommodation despite her high income and the fact that she had lived in the provinces for a majority of that period. The minister had clearly spotted this fact in the story and deemed it to be unacceptable.

But what did we learn just after this? That despite the fact that he had lived in Paris for many years – he had been president of the National Assembly, then a minister – he had kept on social housing-style rented accommodation near Nantes in west France.

This is not social housing as such, even if the sometimes tearful minister wanted people to believe that is what we had written. Instead, it was an apartment bought and then rented out by someone in the private sector under what is known as the “social” provisions of an old property law called the loi Scellier. Under this law the landlord, in return for a tax break, is under a legal obligation to cap the rent on it at a certain level.

There is another issue here, aside from the misrepresentation of how Mediapart reported it. It is that the social measure of the loi Scellier was created to encourage owners to rent the property to people on modest incomes for whom it is sometimes hard to find accommodation, as landlords tend to rent to wealthier tenants. So the law also puts a cap on how much a tenant can earn for them to be able to rent such accommodation.

The rents in such housing are supposed to be lower than on the open market, and in this case we know that some families on low incomes had applied for the flat that de Rugy rented. The estate agent managing the property wrote to de Rugy: “The residence is very pleasant to live in, peaceful, secure, well-situated and demand is high.”

The aim of our article was therefore to raise the following points: what was François de Rugy doing in housing that is aimed at tenants on modest incomes? How was it possible for him to continue to rent there under the social aspect of the loi Scellier when to benefit from that it would have needed to be his principal residence, which had not been the case for a long time?

When Mediapart asked François de Rugy these questions before publishing our article, he did not reply by saying that it was legitimate for him to use this two-room flat as his pied-à-terre in the region when he came home at weekends. Instead, he explained to us that he was unaware that his tenancy was signed under the social aspect of the loi Scellier scheme.

This response featured in the article and it is not impossible that this is true, as there is no mention of the 'social' measure in the lease that de Rugy signed, even if it hard to imagine an estate agency not informing the local MP of the type of housing they were offering him.

Whatever the truth of that, the point is that the minister's argument freed him from what would have been an indefensible position. Faced with the reality of the situation, he says he is the “victim of duplicity by the owner and the estate agency”.

Enlargement : Illustration 4

The regional newspaper Quest-France went even further in an article headlined: “INVESTIGATION: François de Rugy's reduced rent apartment: no one cheated, it's the law”.

The investigation was based mainly on the anonymous statement of a “manager at Crédit Agricole Immobilier” - the agency who rented the apartment to de Rugy – who explained that “his income (the income declared in 2014) corresponded with the cap [on income level allowed for tenants] and by some way! It was almost half: €48,000 [a year] against a cap in this area which is set at €78,000”.

The regional newspaper thus considered that Mediapart's revelations on “this affair of the apartment at Orvault [near Nantes] has fallen flat”. This was an expression eagerly picked up by supporters of the ruling La République en Marche (LREM) party on social media.

However, Ouest-France got it completely wrong. In fact we explained that in view of the limits in force at the time, François de Rugy could not have rented the apartment under this social housing-style arrangement. For the cap on income is calculated according to two criteria: the household income and how many people there are in the household.

The social loi Scellier measure is clearly explained by the Ministry of Finance in its official tax bulletin of May 15th 2009. In terms of income, it is the household's income from two years earlier which is taken into account. In de Rugy's case this indeed corresponds to the 48,000 euros we mentioned in our article and which also appeared in Quest-France's article (it may seem low for an MP but at the time MPs benefited from a very advantageous tax regime).

However, when it come to calculating the size of the family, this is based on how many people will use the property on the day the lease is signed. According to the law in force at the time: “So, for leases signed during the year 2009, the relevant income of the tenant from 2007 is compared with the cap applicable to the tenant's family situation in 2009, at the date the lease is signed.”

Yet François de Rugy took on this housing after he separated from his wife, who kept charge of their two children. De Rugy himself lived alone in the flat and his children only stayed some weekends - hence why he rented a one-bedroom flat – as he himself has accepted.

In the Nantes suburb of Orvault, which is located in zone B1 of the agglomeration, the cap on incomes for leases signed in 2016 was €34,790 for a single person. That is the limit that should have applied to François de Rugy and prevented him from having this accommodation. For the €78,000 cap mentioned by the estate agent in Ouest-France related to the limit when you have two children with you.

How could the agency have made such a major mistake? Did they want to do François de Rugy a favour with or without his agreement? The agency did not respond to Mediapart's questions. But in all likelihood the agency had not got it wrong, but rather it was misled – by François de Rugy himself.

On the “list of documents to supply” by the tenant there was an “information sheet” to fill in about his new accommodation and his personal situation. François de Rugy filled in some parts, in particular some which related to the make up of his family. He stated that he was “single”. On the line which asks “Number of children” he had marked two. But to the question “Do they live in the apartment” he gave his answer as “yes”.

Enlargement : Illustration 5

The estate agency then calculated the income cap on the basis of a family situation which did not correspond to the reality on the date the leases was signed.

Did François de Rugy get in wrong it good faith? Did he misunderstand? As he did for the social loi Scellier measure, which he says he did not know applied to this flat, perhaps the former minister will go on the radio one day and explain that it all stemmed from a terrible misunderstanding.

It is still a matter of fact that he really should not have been in that housing.

Did he misuse his expenses as an MP?

Despite his PR campaign, François de Rugy could not get away from one fact: that he had diverted his expenses as an MP, an allocation of money known in French as IRFM. This account is supposed to be for funding Parliamentary activities but in his case some of it was used for personal matters, namely paying for subscriptions to his political party at the time.

De Rugy never took the risk of denying this information which was published by Mediapart on July 16th, just after his resignation as environment minister, because it was perfectly correct and documented: including the sums down to the nearest euro, the dates, the payment methods and so on.

Enlargement : Illustration 6

So François de Rugy used a new line of defence, claiming that the rules on how the expenses or IRFM should be used were not as clear in 2013 and 2014 when the payments were made as they were later. He based his argument on the fact that it was not until 2015 that the office at the National Assembly gave MPs a “guide” in which it is specified that subscriptions to political parties are among “banned expenses”.

But the former minister's argument is a very flimsy one for a Parliamentarian who for several years had made a name for himself politically by calling for stronger controls over MPs' expenses.

Is this the same MP who, as a member of the opposition in in October 2011, had joined others in putting forward legislation seeking to oblige Parliamentarians to make public the way they used their allowances to pay for expenses relating to their work as an elected representative? If so, it is hard to imagine that he did not know the rules, given that he wanted to improve them.

As Mediapart has already stated (see here and here), it was perfectly clear and in the public domain well before 2015 that the IRFM account was not to be spent on anything other than activities linked to a Parliamentary term of office. Since the law on political funding of 1988 it has certainly not been provided to pay subscriptions to a political party.

MPs were also reminded of the rule in 2013 by the National Assembly's ethics officer. “The payment of a subscription to a political party is not an expense associated with a term of office,” they stated in their annual report. And in its report for 2012/2013 the national election spending and political funding commission the Commission Nationale des Comptes de Campagne et des Financements Politiques (CNCCFP ) noted: “The IRFM can in no cases be used to pay a subscription to a political party.”

Had François de Rugy simply missed these reminders about the rules? “I personally sent this report to all the heads of [political party] groups at the National Assembly and the Senate. So as president of the EELV [editor's note, the green party of which De Rugy was then a member] at the Assembly, François de Rugy cannot have been unaware of this rule,” the CNCCFP's president François Logerot told Libération.

In our initial article on this issue on July 16th we raised the theory that the MP could have repaid these expenses, as had been done by several Parliamentarians already criticised by Mediapart in this respect. “Has François de Rugy ever reimbursed these wrongly-used expenses?” we asked then. The former minister did not come back to us on this at the time.

The response finally came a week later when the elected representative declared that he remembered that he had eventually repaid the money drawn from his IRFM expense account. He even stated: “If I had had immediate access to my bank statements I would never have resigned.”

It is worth noting at this point that, as with the misappropriation of assets in a company, the mere fact of paying the money back later does not change things.

But according to François de Rugy's account, this irregular use of the IRFM expense account for MPs is simply a form of “cash advance”. He even told the fact-checking site CheckNews that he had “reimbursed the sums when he could”.

And on BFM TV de Rugy stated: “I think many people can understand this. You know, when you don't have the money in one account, you take it from another, and later you pay it back.”

So even if he did reimburse the money (which is not yet confirmed – see below), François de Rugy granted himself off his own bat an interest-free loan, repayable how and when he wanted, with public money. If it were not just confined to the former minister, this kind of “de Rugy measure” would doubtless be popular among the thousands of French households who are instead currently forced to take out short tern loans, often at exorbitant rates of interest, to get by.

When it comes to the repayments themselves, François de Rugy's defence case is not yet complete. To show good faith he gave two monthly bank slips to the investigative magazine Le Canard Enchaîné on Monday July 22nd. Two days later the weekly referred to the ex-minister's “counter attack” in a short article.

This idea of a “reimbursement” was then relayed without question by several other media outlets.

Yet there are some grey areas over this story of repayments. The two bank slips provided by François de Rugy show that he “repaid” his IRFM account with his own money the sum of 6,500 euros on August 20th 2014, then 3,200 euros on July 23rd 2015, making a total of 9,700 euros in all.

Yet these payments do not tally with the subscription payments made to the green EELV party. On December 26th 2013 de Rugy transferred 7,800 euros from his IRFM account to his party. A year later he signed a cheque for 1,400 euros.

That means de Rugy “reimbursed” 6,500 euros in August 2014, while he had drawn out 7,800 euros from his IRFM account. He only made up the difference a year and a half later, showing in doing so the limitless flexibility of his concept of “cash advance”.

The figures do not add up either; there is a discrepancy of 500 euros between the subscriptions and their “reimbursements” (9,700 euros reimbursed against 9,200 euros in subscriptions).

This gives rises to the following, still unanswered questions: were the cheques of August 2014 and July 2015 really used to compensate for the EELV party subscription payments? If so, why did the sums never tally? If not, were they paid to reimburse other things? We still do not know. François de Rugy has declined to show all of his IRFM payment slips to journalists who have asked for them.

There is one final aspect of our investigation which the former minister's defenders have tried, also in vain, to attack. In our article on July 16th we pointed out the tax difficulties raised by payments to a political party – which give right to a tax deduction – using the IRFM expense account which is itself already exempt from tax.

We wrote how in 2014 François de Rugy had paid 1,400 euros of his subscriptions from his IRFM expense account, and that he had later offset all of his subscriptions that year (in all the party dues were 14,400 euros) in his 2015 tax return (which was based on his 2014 income). This information came from de Rugy's office itself after we had raised some questions with it several days before.

“Donation [editor's note, i.e. subscriptions] amounts which are not taken into account can be deferred for 5 years,” the minister's office explained at the time. A few days later the minister's supporters wanted to reassure on the issue. “In any event, that represents a deduction of less than 6,000 euros,” his “entourage” told the Journal du Dimanche on July 20th.

But on August 2nd the line of defence abruptly changed. The magazine Capital – which somehow omitted to tell its readers that it belongs to the same group as the magazine Gala which employs Séverine de Rugy, and that its editor took part at a dinner given by François de Rugy at the president of the National Assembly's official residence – published an article explaining that Mediapart's information on the tax deduction in 2015 was simply “false”. The magazine even went as far as claiming that we had accused François de Rugy of tax fraud, something we had never said.

As soon as it appeared this article quickly spread on social media, especially among Macron supporters. Even a member of the government got involved. Junior finance minister Agnès Pannier-Runache, who by a quirk of timing knew that we were preparing to publish an investigation concerning her (she had just responded to our questions, see here), wrote an angry Tweet (see below). She declared: “So [François de Rugy] told the truth. We're waiting for a correction from Mediapart? Unless it's not the truth that is the priority for Mediapart but a political project hidden behind the trappings of investigative journalism?”

CQFD... Donc @FdeRugy a dit la vérité. On attend le correctif de @Mediapart ??? A moins que ce ne soit pas la vérité la priorité de Mediapart mais un projet politique dissimulé derrière les oripeaux du journalisme d’investigation ? Calomniez, calomniez il en restera tjs qqch. ! https://t.co/bLFqDDAmJ4

— Agnès Pannier-Runacher (@AgnesRunacher) August 4, 2019

The Socialist Party's first secretary Olivier Faure also referred to the article, noting: “The information comes very late but it clears François de Rugy of any tax fraud. That deserves to be known. A man's honour is worth something.”

Similarly Daniel Schneidermann, director of Arrêt sur Images, a website about the media, made a mistake when he Tweeted (see below): “After Le Canard revealed that he had reimbursed [the party subscriptions] Capital magazine shows that Rugy could not have have asked for a tax deduction on his subscriptions paid with the [MPs expenses] as he was already well over the threshold.”

Après Le Canard qui révèle qu'il avait remboursé, @MagazineCapital démontre que Rugy ne pouvait pas demander de déduction fiscale sur ses cotisations payées avec les frais de mandat, puisqu'il explosait déjà tous les plafonds. https://t.co/0q3Z4QSKyA

— Daniel Schneidermann (@d_schneidermann) August 6, 2019

The thrust of the article in Capital, for which according to what de Rugy told CheckNews he was the only source, goes like this: the MP had taken care, in declaring the donations which might give rise to a tax deduction, to exclude the subscriptions paid from his IRFM expense account in 2014.

Capital also supplied a similar explanation for the MP's 2013 income – dealt with in his 2014 tax declaration – in relation to which we had not mentioned tax deductions for the very good and simple reason that we have never seen the ex-minister's tax declaration for that year, unlike the one for 2015. Capital thus thought it was worth denying something we had never written.

When other media contacted us after the publication of that article we immediately informed them that Capital's reasoning did not hold water.

And in fact this counter attack by the MP's supporters failed too. On August 23rd two journalists from CheckNews demonstrated Capital's mistake. Yes, François de Rugy had indeed offset his 2014 party subscriptions paid for from his IRFM account, confirming what we had written and what the minister's office had told us in July.

In relation to 2014, the only year about which we raised the issue of potential tax difficulties, the tax declaration (which was made in 2015) which Capital got hold of “in fact proves the opposite of what the magazine writes,” concluded CheckNews (see full story in French here).

On August 23rd Capital published an “update” at the beginning of its article following a “long and detailed second investigation to check the veracity of our information”. This second probe confirmed, said Capital that “as we wrote, François de Rugy did not in 2014 [editor's note, in the tax declaration relating to 2013 income] deduct from his taxable income the sums that he had taken from the IRFM the previous year (7,800). However, it appears that the ex-minister of the environment did do so the following year [editor's note, in the 2015 declaration relating to 2014 income] in relation to a much smaller sum (1,400 euros). Duly acknowledged,” wrote the journalist.

The conclusion is that the information given by Mediapart on the basis of the 2015 tax declaration was perfectly correct.

-------------------------

If you have information of public interest you would like to pass on to Mediapart for investigation you can contact us at this email address: enquete@mediapart.fr. If you wish to send us documents for our scrutiny via our highly secure platform please go to https://www.frenchleaks.fr/ which is presented in both English and French.

--------------------------

- The French version of this article can be found here.

English version by Michael Streeter