While money is not everything in football, it certainly plays a major role in the professional game. Over a period of just a few years, PSG has distanced all potential rivals in France’s top-flight Ligue 1 division and carved a place for itself among the biggest teams in Europe. But, according to documents obtained by German news magazine Der Spiegel, gathered under the project Football Leaks, (see more on the source here) and studied by Mediapart and its partners in the media network European Investigative Collaborations (EIC) behind the sporting achievement is a backdrop of cheating the financial rules of the administrative body governing European football clubs, the Union of European Football Associations (UEFA).

Enlargement : Illustration 1

The EIC investigation also reveals that despite internal investigations that were damning for PSG, the club’s financial malpractice was covered up by two senior UEFA officials until 2016, namely Michel Platini, who served for eight years as the body’s president until 2016, and Gianni Infantino, its general secretary from 2009 to 2016 and who is now president of FIFA, the worldwide governing body of association football.

Since Qatar bought PSG it has ploughed 1.8 billion euros into the club. That sum represents more than 11 years of spending by French Ligue 1 club Marseille, or the cumulated budget over 34 years of its other Ligue 1 rival Montpellier. It is the second biggest case, just behind English club Manchester City, of financial ‘doping’ of a club since UEFA introduced its regulations banning the practice.

Enlargement : Illustration 2

Officially, financial investment in clubs is not a free-for-all, following a major 2010 reform that UEFA adopted under Michel Platini’s leadership. The object of the reform, called the Financial Fair Play Regulations (FFPR), is both to put a brake on the spiralling sums involved in player transfers and salaries by prohibiting clubs from running up a deficit, and to prevent emirs, oligarchs and other super-rich club owners from distorting the sporting balance of competitions, involving clubs of much more modest means, by pumping seemingly infinite sums into their own teams.

To enforce respect of the regulations, UEFA has a major weapon in the form of applying a temporary ban on a club from taking part in the prestigious European Champions League or the second-rated Europa League. However, PSG and Manchester City were to escape any such penalty, while other clubs including Turkey’s Galatasaray and Italy’s AC Milan (which eventually successfully appealed the sanction) were handed down an exclusion from the tournaments for breaching the rules by much lesser sums.

Platini and Infantino had promised to be unyielding in applying the FFPR. “If the question is to know whether I would have the courage to punish prestigious clubs, the answer is yes,” said then UEFA president Platini in 2011. “We are not here to kill clubs, even if we could severely punish them if that was needed […] there will be no preferential treatment,” he was to add in 2013.

Speaking in 2011, Infantino, then UEFA secretary general, underlined that “financial doping” was “a spiral” that could lead football into “disaster”, and that if clubs violate the regulations “we will impose the hardest of punishments”.

But despite such pronouncements, Platini and Infantino covered up what was a massive fraud by the owners of PSG. The blurring of the rules by UEFA continued, to a lesser degree, under the presidency of Slovene Aleksander Ceferin. One of the Football Leaks documents indicates that PSG was “for political reasons” absolved of wrongdoing by the organisation in June 2018, when significant financial restrictions only were imposed. In a rare move, that decision was questioned by the head of the independent body that oversees the application of the financial fair play rules.

Questioned by the EIC, Aleksander Ceferin, Gianni Infantino and Michel Platini gave a largely general response (click on the ‘More’ tab, top of page) in which they argued that the financial fair play programme had in their opinion proved a success, and that the UEFA body responsible for applying disciplinary measures against clubs that breached them had acted in all “independence”. UEFA said that those who breach the rules are only excluded from participating in the Champions League competition as a “last resort”, and when their proposed plan for returning to balanced accounts is not deemed credible.

Michel Platini, 63, insisted that “severe” punitive measures had been applied to clubs, while he underlined also that he had “always affirmed that Financial Fair Play did not have for vocation ‘to kill’ or financially asphyxiate European clubs that infringed the rules”.

Enlargement : Illustration 3

For its part, PSG gave a written reply to the EIC’s questions (see ‘More’ tab) in which it refused to answer most of those submitted to it, citing “obligations for confidentiality”, adding: “Your questions show that you dispose of confidential documents. We have every reserve about the manner in which these elements were obtained and will be used.” The club described the EIC’s questions as “biased” and said it had “the impression that this investigation is exclusively to incriminate whereas the club has never hidden any element to controlling bodies […] and has always respected applicable legislation”.

But the club did grant the EIC a long interview with its general manager Jean-Claude Blanc and its secretary general Victoriano Melero (see Boîte Noire, bottom of page). PSG is critical of the financial fair play programme, which allowed de facto an advantage to clubs such as Spain’s Real Madrid, or England’s Chelsea, which employed financial doping before it was outlawed.

Blanc told the EIC that, by “preventing shareholders to invest freely”, the financial fair play rules “has become an instrument in the hands of some, backed by UEFA, to prevent new entrants from joining the elite circle of two Spanish clubs, one or two Italian clubs, a German club and a few English clubs, which since 15 years monopolise all the European titles”. He added that despite this, PSG had shown itself to be “exemplary”, and has acted “absolutely” in accordance with the rules in place.

Enlargement : Illustration 4

According to investigations by French magazines So Foot and France Football, it was on November 23rd 2010, nine days before the attribution of the host country for the 2022 World Cup, then French president Nicolas Sarkozy held a lunch meeting at the Elysée Palace, the French presidential office. His guests, according to the reports, were Tamim bin Hamad Al-Thani, then Crown Prince of Qatar and now the Gulf state’s ruler, along with then UEFA president Michel Platini and French businessman Sébastien Bazin, who represented the Colony Capital investment fund, majority shareholder in PSG and which wanted to sell the loss-making club. Sarkozy, a supporter of PSG, reportedly proposed a deal for the Qatari prince by which he would purchase PSG and create a sports TV channel in France, in exchange for Platini’s help in securing his country as host of the 2022 World Cup.

Platini, once a celebrated French footballer and the first retired player to lead UEFA, has consistently maintained that during the lunch Sarkozy did not ask him to be involved in such a deal, although he said he did “feel that there was a subliminal message”. Platini has also said he was at the time opposed to the purchase of PSG by Qatar, and that Sarkozy had tried to convince him otherwise. “He told me that the Qataris were good people,” Platini told So Foot. Contacted by Mediapart, Sarkozy declined to comment on the lunch meeting other than to say that Bazin was not present.

In the event, everything was to work out well for both Prince Tamim and the French president; Platini voted in favour of Qatar being awarded the World Cup (Platini insists he did so out of personal conviction), which it was, and in June 2011 Qatar bought PSG.

Tamim had major ambitions for the club, as outlined in a confidential document entitled “PSG strategic plan, 2012-2017”. The plan was for the club to become one of the top five worldwide, and to reach the Champions League semi-finals in 2016. He planned to invest, over a period of five years, 1.3 billion euros for the purchase of players and for their salaries. PSG, meanwhile, appeared to be well aware that such a sum infringed UEFA’s financial fair-play rules. “These rules will create a serious problem […], regular lobbying action will be required,” the confidential club document concluded.

But the Qatari emir apparently went about things as he pleased. Two years after buying the club, Qatar Sports Investments, a state-run fund, had already spent 400 million euros on buying 21 players, including stars like Zlatan Ibrahimovic and Edinson Cavani. Over that period, the club’s wage bill had tripled.

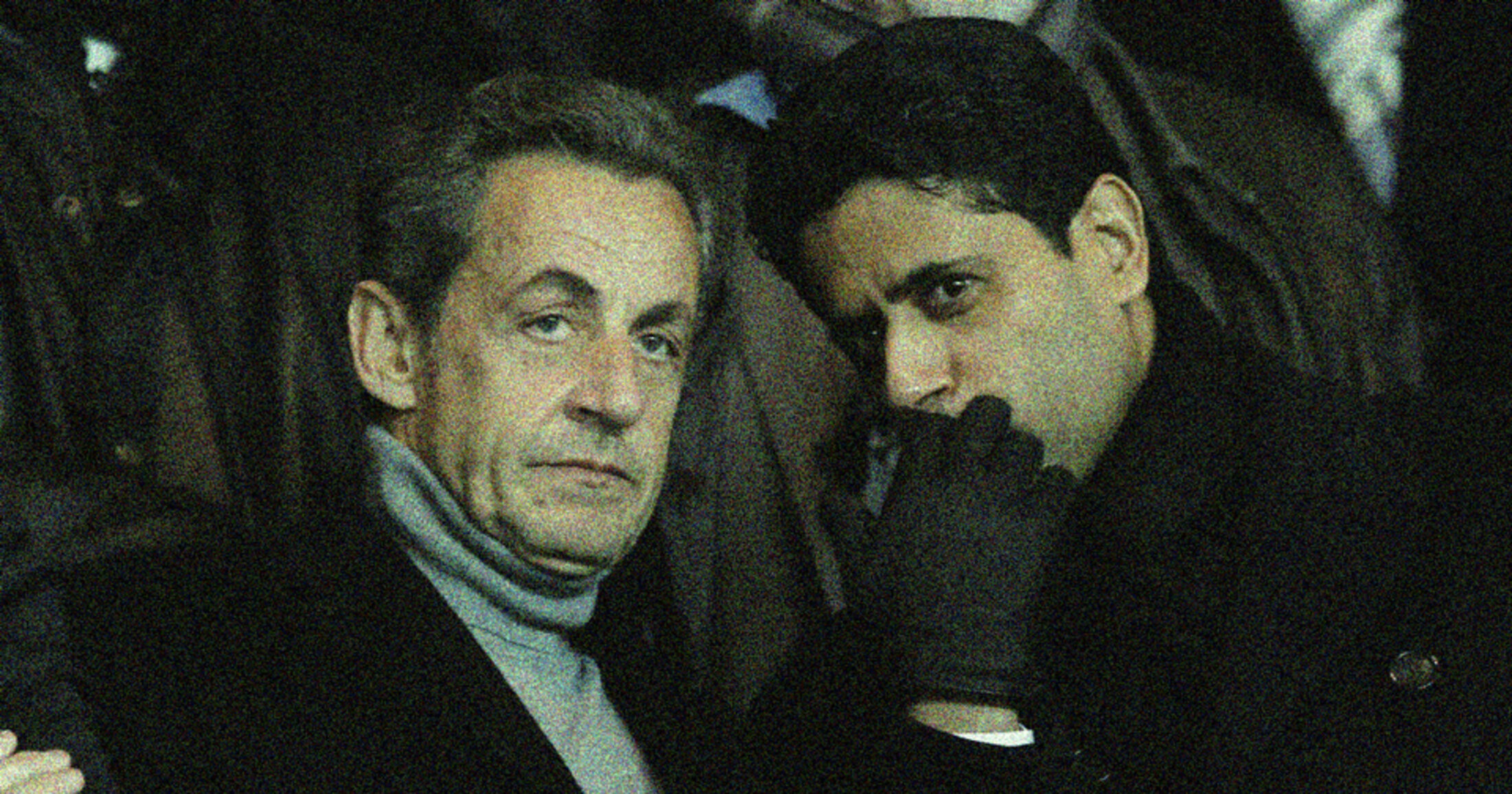

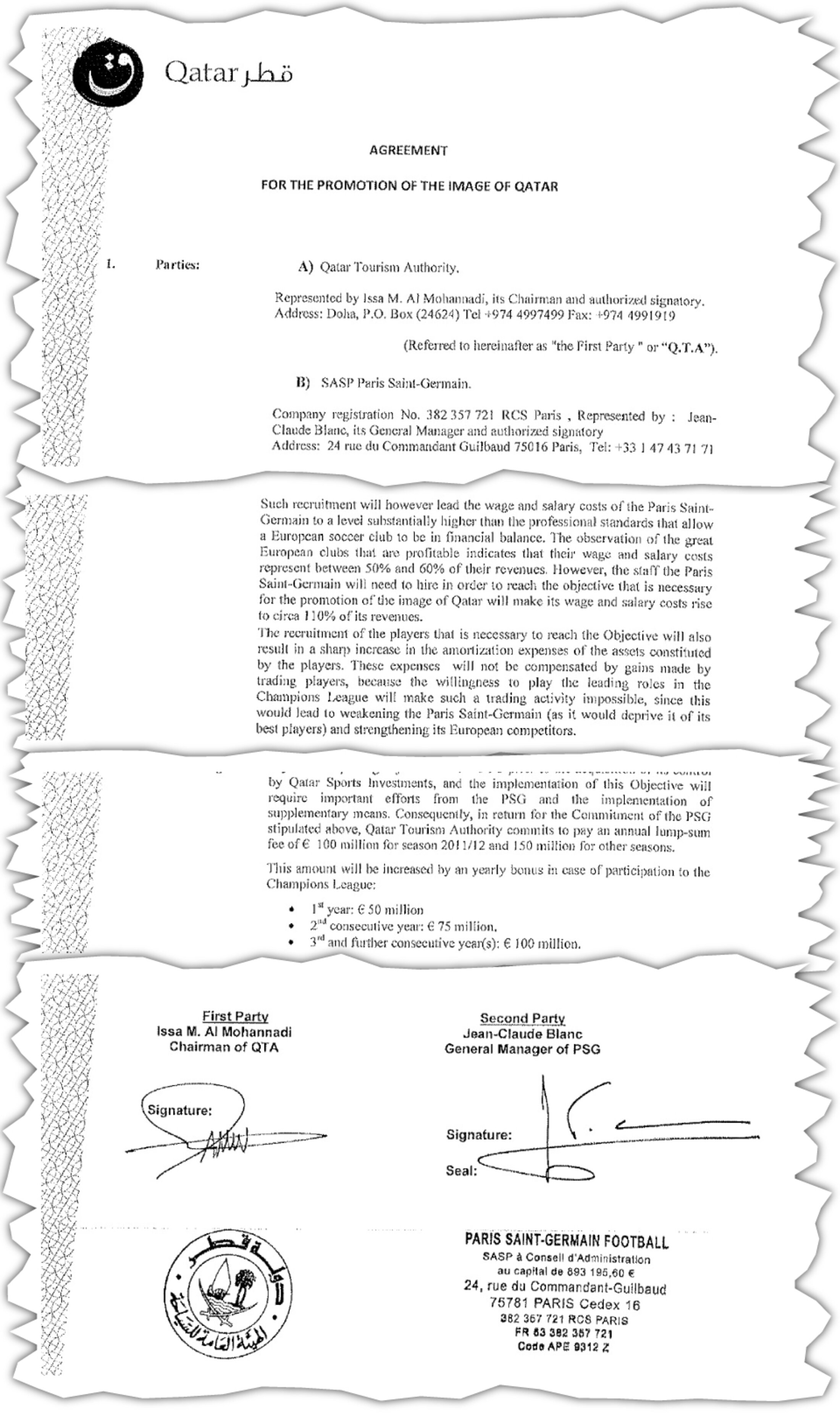

In June 2012, the Qatari-owned PSG ended the season at the top of France’s top-flight division Ligue 1. As a result, the club was among the teams qualified for the Champions League, and was required to abide by the financial fair play rules. Two months later, and in all secrecy, PSG signed a contract with the state-run Qatar Tourism Authority (QTA) for the “promotion of the image of Qatar”. Under the terms of the contract (see document immediately below), the QTA was to give PSG 1.075 billion euros over five years – an average of 215 million euros per year – with 100 million euros in the first season, and up to 250 million euros the following years.

Enlargement : Illustration 5

The amounts were extraordinary, and notably in comparison with the 24 million euros in sponsorship deals the club had previously been receiving. In 2012, leading European clubs Real Madrid, Barcelona and Bayern Munich separately received around 30 million euros for kit sponsorship deals. The QTA had agreed to pay around six times more without in return having any presence on the PSG strip or at the club’s ground, the Parc des Princes. PSG was only required to refer to Qatar in its PR and corporate communications, and to take part in a yearly promotional event. The principal requirement was that PSG should “recruit players […] of the highest European level”.

The contract detailed that “the state of Qatar” had bought PSG “to develop its role and international recognition as a major actor in the sporting field”. In order to promote the image of Qatar, PSG was to “play a major role in the Champions League”, and therefore to attract star players and spend “110%” of its current revenues on their salaries. It sets out clearly that the QTA’s aim, driven by the emir’s quest for grandeur, was to absorb the PSG deficit.

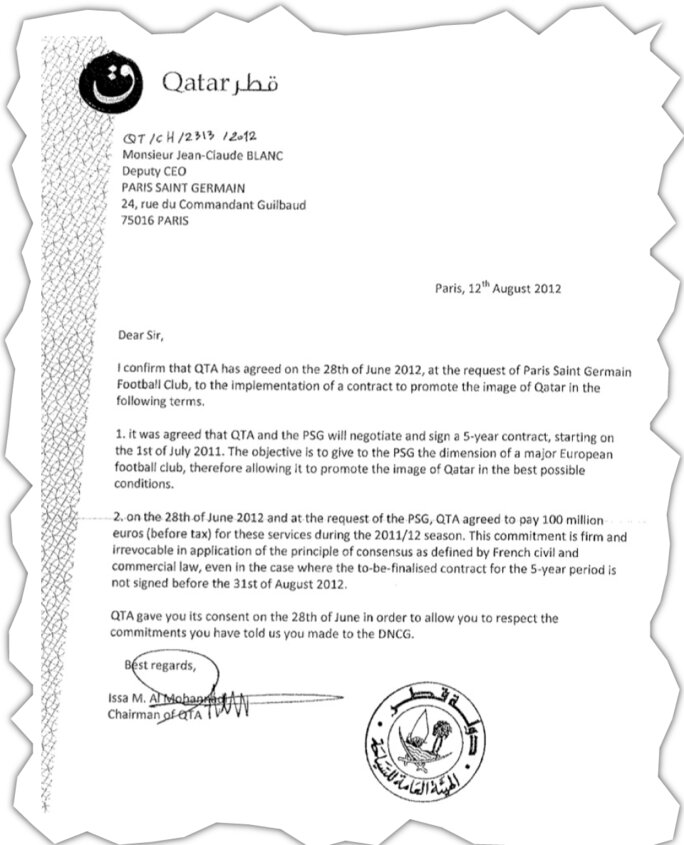

But that was far from the only anomaly. Under the contract signed on August 8th 2012, QTA accepted to hand over 100 million euros for the 2011-2012 football season which had ended two months earlier. To justify this, the QTA president put in writing (see document below) that an agreement had been reached on this partnership during a meeting with the club on June 28th 2012, when it had requested the retroactive payment of 100 million euros in order to “respect it commitments” to the French watchdog for financial affairs in football, the DNCG. The head of the QTA gave an oral agreement to hand over the money, although the contract with PSG was finally never signed.

Enlargement : Illustration 6

PSG general manager Jean-Claude Blanc told Mediapart that he does not remember the existence of the letter from QTA’s president and that PSG had “no need” for such funding with regard to the DNCG. However, the situation was clearly set out in the document published above.

When Platini, Infantino sidelined UEFA investigators

Furthermore, during the 2012-2013 season, the existence of the contract was not made public and the QTA engaged in no promotional activity with PSG. Thus the Qatari tourism authority had that year spent 200 million euros (or 300 million euros when taking into account the retroactive payment of 100 million euros) apparently for nothing.

Jean-Claude Blanc told Mediapart that the contract was retroactive because it had “begun to serve Qatar” as of the year preceding the signature.

As of February 2013, which was five months before UEFA began its first study of PSG’s accounts, Blanc brought together a team of high-level lawyers to attack the financial fair play rules before France’s competition regulator, the Autorité de la concurrence. The aim was to frighten UEFA and force it into a compromise.

The complaint was drawn up but was finally never lodged. “We envisaged it several times but up until now the club and its shareholders have always been respectful towards the UEFA institution,” said Blanc. “We don’t want to put ourselves in a position of legal aggressiveness [and run the risk of] being excluded from European competitions.”

PSG also commissioned the services of French advertising and PR giant Havas in an attempt to justify the value of the contract. The Havas team came up with the idea of calling it an example of ‘Nation Branding’, which allowed for the argument that the contract could not be compared to traditional sponsorship deals. PSG, meanwhile, urged the QTA to “activate” the partnership, which was unveiled on October 29th 2013 during a press conference and the announcement of an initial QTA advertising campaign across the Paris metro underground train network.

But UEFA was unconvinced. In May 2013, Michel Platini, then its president, observed: “It’s not possible to have a sponsor for 300 million euros […] it’s not right, it’s not the market price.”

To monitor respect of its financial fair play regulations, UEFA created a Club Financial Control Body (CFCB), an “independent” body with an “investigatory chamber”, led by a “chief investigator”, and an “adjudicatory chamber” for the judging of cases. It commissioned two expert reports and asked for the “opinions” of three eminent international jurists who were unanimous in their findings. Takis Tridimas, professor of European Law at King’s College London, commented that the contract “is not a true sponsorship agreement and is designed to circumvent the FFP Rules”.

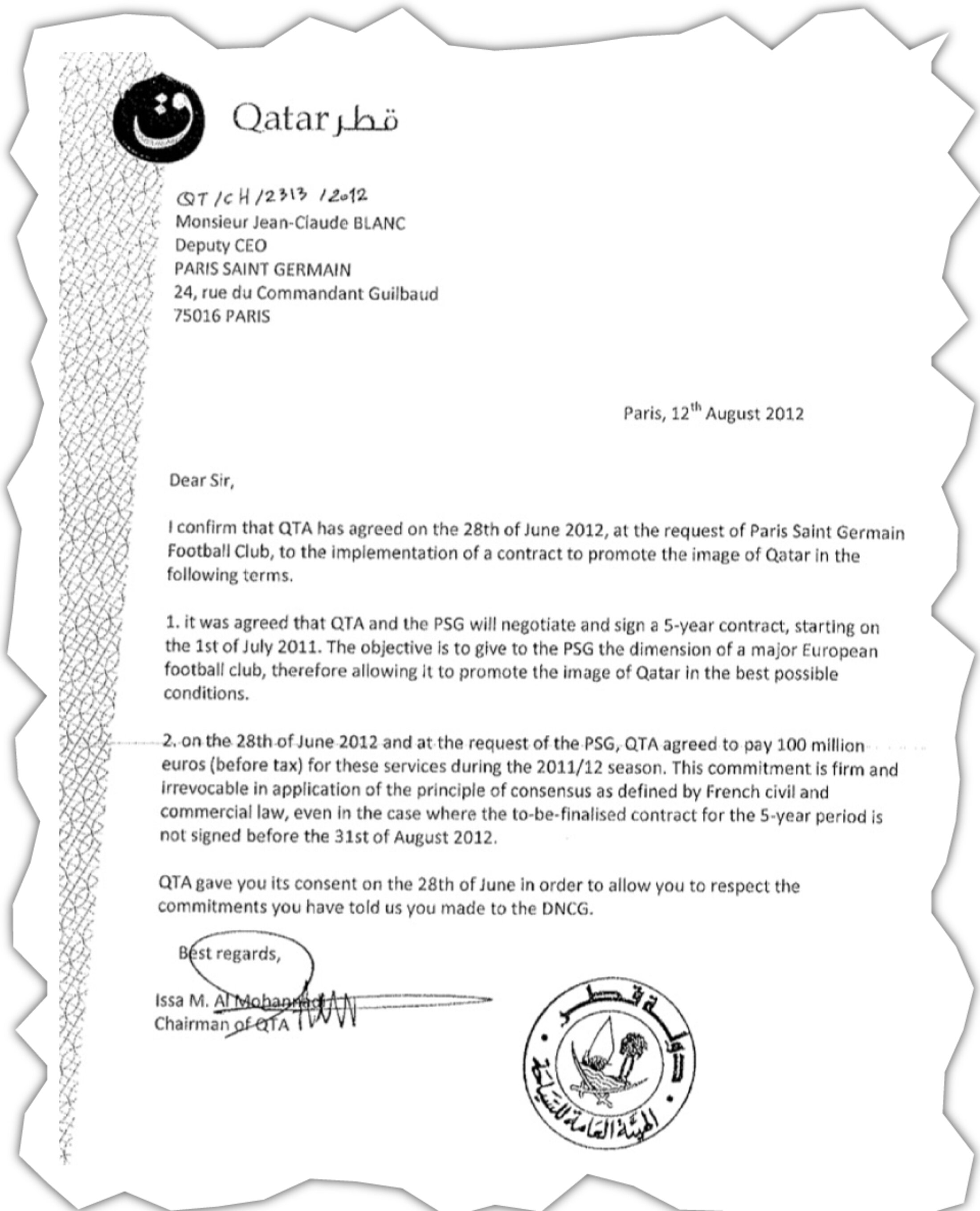

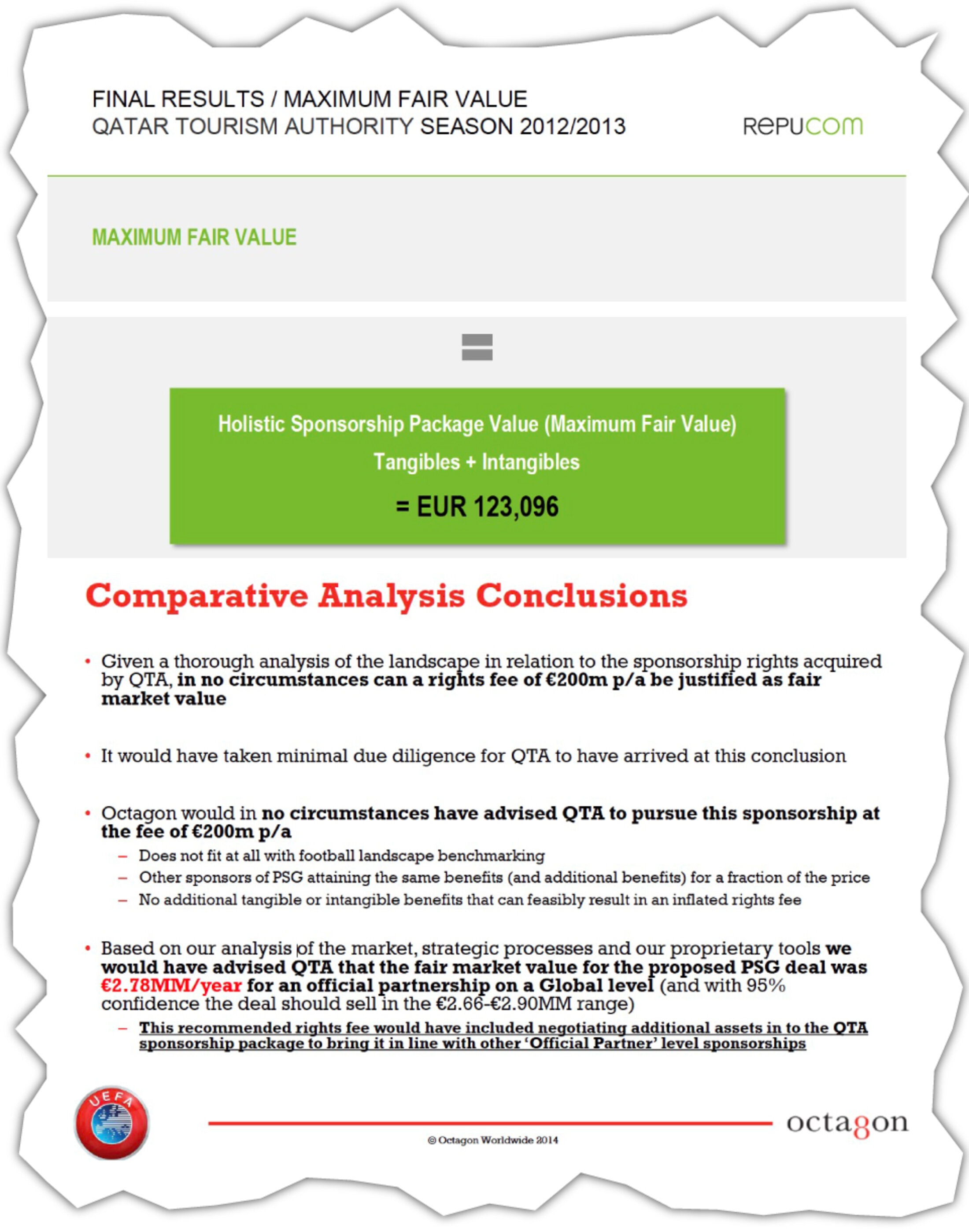

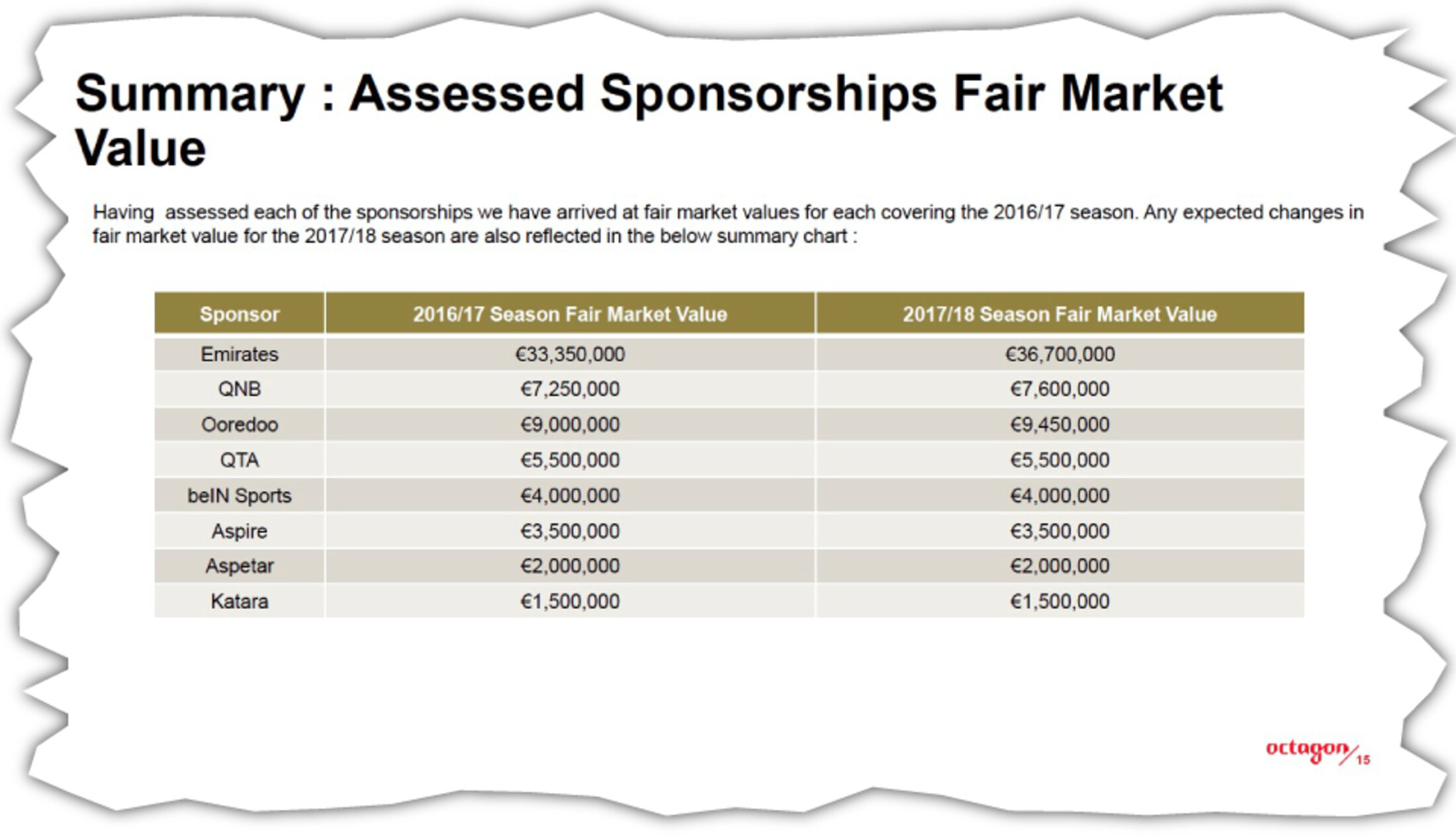

The expert evaluations were damning: Repucom, a leading agency among those specialised in researching sports marketing and sponsorship activity, valued the publicity gains for the QTA from its alliance with PSG at about 123,000 euros per year – which was 1,600 times less than the amount it gave to the club. Octagon, another agency in the same field and highly reputed worldwide, looked at comparable deals elsewhere and concluded that the contract was worth 2.78 million euros per year. “QTA pay a rights fee that is hugely inflated within the sport […] It would have taken minimal due diligence for QTA to have arrived at this conclusion,” reported Octagon.

Enlargement : Illustration 7

PSG contests the veracity of the evaluations on the basis that the contract is not for sponsorship as such but for “nation branding”, comparable to a country’s hosting of the Olympic Games or a Formula 1 race. Because PSG is the only entity to apply this concept “in the football of clubs” it argues that the QTA contract cannot be compared to any other. Jean-Claude Blanc claimed that “for the visibility that was given, it’s not very expensive”.

On April 8th 2014, a lawyer for UEFA's CFCB investigatory chamber drew up a final report which was to be signed by the body’s chief investigator. The document concluded that the QTA contract was not only “massively overvalued” but also that it had been conceived “to circumvent the rules” of financial fair play.

Questioned by the CFCB investigators, PSG was unable to provide the least written evidence that it had negotiated with QTA. The investigation established that when the club received the first payment, in April 2013, of 300 million euros, PSG immediately handed 283 million euros to its principal shareholder, QSI, to pay back the money spent on buying new players who had arrived since the Qatari takeover of the club.

The CFCB report concluded that the true value of the QTA contract was nil for the 2011-2012 season (the object of the retroactive payment) and worth 3 million euros for the 2012-2013 season. When putting to one side the funds handed over by QTA, the PSG would have notched up a deficit of 260 million euros over two years, a sum that is almost six times higher than the authorised limit.

The report was due to be signed by chief investigator Brian Quinn, a Scottish economist and former chairman of Celtic plc, the owners of Celtic football club. But Quinn never signed the document. Furthermore, the final report and the expert evaluations of the value of the QTA contract were never passed on to PSG. “We never saw these reports,” said Blanc.

Enlargement : Illustration 8

In February 2014, PSG president Nasser Al-Khelaifi and its general manager Jean-Claude Blanc held a meeting at UEFA’s headquarters in Switzerland with Michel Platini and Gianni Infantino. According to documents obtained from Football Leaks, Al-Khelaifi began by warning Platini that he had nothing to gain by attacking Qatar via PSG. Which raises the question of whether that was an allusion to the fact that Platini’s son, Laurent Platini, was employed by a subsidiary of QSI, the main shareholder of PSG, or possibly a reference to the November 2010 lunch at the Elysée Palace. Contacted, those who took part in the meeting declined to answer our questions.

According to the documents obtained from Football Leaks, Platini and Infantino (who became FIFA president in 2016) proposed reaching an amicable agreement. PSG’s management accepted the idea, but on condition that the negotiation was conducted at the highest level and without the involvement of the CFCB investigatory chamber, which Platini and Infantino agreed to. However, in public the pair had insisted on the “independent” status of the chamber, as guaranteed by UEFA regulations.

Secret negotiations began, principally between Blanc and Infantino, but also involving Platini. Al-Khelaifi and Blanc rarely refer to Platini by name, instead calling him “the top guy”.

At the end of March 2014, an initial preparatory session is organised, without the presence of the four men, between representatives of PSG and UEFA. The UEFA team argued that the value of the QTA contract was virtually nil, and that it was not plausible – which the PSG side accepted. The UEFA officials then asked the PSG representatives to help them make it credible.

It is from there that an idea which would allow to cover up the irregularity was found. This entailed drawing up a new contract which would appear sufficiently credible for UEFA to estimate its value as being high, and without losing face. There then remained the question of putting a precise figure on the value.

Everything was played out in London on April 8th when, in a secret meeting with Jean-Claude Blanc, UEFA’s Gianni Infantino accepted to evaluate the QTA contract’s worth at 100 million euros, despite the fact that he knew independent experts had valued it to be worth, at the very most, 3 million euros.

Infantino was so embarrassed that he asked for the figure not to be mentioned in the official agreement but instead in a “side letter” which would remain secret. Infantino was concerned that “other clubs exercise (with success) a recourse against the agreement”. But PSG did not give in. Blanc wrote to Al-Khelaifi: “I just talked to Gianni who pushed me to accept a side letter for the QTA amount [but] I refused.”

Enlargement : Illustration 9

By reducing the QTA contract from 200 million euros to 100 million euros, Blanc warned Al-Khelaifi, PSG would be hit with “a deficit of 100 million euros in 2014-2015”. When Infantino was informed of this he suggested that PSG reduce its spending, which the club refused to do. Infantino wavered once again.

According to Football Leaks documents, it was on the sidelines of a Ligue 1 Cup final between PSG and Lyon on April 19th 2014 at the Stade de France that Infantino and Blanc entered into negotiations. The UEFA secretary general accepted that the loss from the re-valued QTA contract should be almost entirely compensated by funds from new Qatari sponsors. The victory was total for PSG, who on the field beat Lyon 2-1 thanks to two goals from Edinson Cavani, the Uruguyan star who PSG had bought for 64 million euros as a result of financial doping which Infantino had just agreed to.

“That’s false, there was no meeting at the Stade de France, there was no agreement about 100 million, there was a decision by the investigatory chamber,” Jean-Claude Blanc told Mediapart.

There remained the formality of getting the “independent” investigatory chamber to validate the agreement that had been reached behind its back. Jean-Claude Blanc was confident of this. “Gianni Infantino called me last night to tell me that [he] had made progress with the panel,” wrote Blanc on April 16th. On May 1st, he wrote to Nasser Al-Khelaifi: “Tomorrow when we sign, please remember to call the top guy for information.”

The following day, the investigatory chamber met to study the agreement reached with PSG. But chief investigator Brian Quinn refused to sign the document. According to a source close to the case, Quinn told his colleagues that he found the agreement was “too lenient” towards PSG. In the middle of the hearing, Quinn resigned from his post as chief investigator, and the chamber hurriedly elected one of its members – Italian academic Umberto Lago – to replace him. Lago just as soon signed his approval of the agreement.

PSG came out well, with a fine of just 60 million euros and the imposing of two years of financial restrictions, which included: a ceiling on its wage bill, a limit to the number of its players and a net balance on transfer deals (purchases-sales) restricted to 60 million euros per year. The club also pledged to return to financially break even within two years. With the QTA contract handing the club 100 million euros per year, and the secret authorisation to gain new Qatari sponsors, none of this appeared insurmountable.

‘Nation states unused to complying with bodies like UEFA’

But the tensions continued, when PSG discovered that English club Manchester City was to be hit with a lesser fine. Nasser Al-Khelaifi was furious; the owner of Manchester City, Sheikh Mansour, was deputy prime minister of the United Arab Emirates and a member of the Abu Dhabi royal family. For Al-Khelaifi , the honour of Qatar was at stake and there was no question of being less well treated than the UAE, and he demanded the amount of the fine imposed on PSG to be kept secret. He wrote to Infantino: “We will not accept that UEFA announce the level of money and we don't want UEFA treat any other clubs better conditions than our club.” For the emirate, to be punished, however lightly, was regarded as a humiliation.

On May 11th, Blanc called Infantino and the “top guy”. Platini called back the following day: PSG would not succeed with its demand that the sum of the fine be kept secret, however it would obtain the same deal agreed with Manchester City, and the fine that was imposed on the club was reduced from 60 million euros to 20 million euros.

But PSG wanted yet more concessions. In the Champions League, a club can line up a squad of 25 players, of who a minimum of eight have been “locally trained”. PSG was unhappy about the situation, and Platini accepted to seek the approval of a “clarification” of the rules by UEFA’s executive committee, which brought down the required number of locally trained players to five when a club can only align a squad totalling 21 players.

With UEFA yielding its position on almost everything, there was serious unease. On April 28th 2018, its legal director attempted to defend the deal. “This settlement is by no means an “embarrassment” nor in any sense is it a “capitulation” to PSG”, he wrote, arguing that Qatar and Abu Dhabi had accepted to “comply with the system”.

Enlargement : Illustration 10

The following passage in what he wrote can be regarded as a lesson in the reality of the power balance in the football business. The legal director wrote that to exclude from the Champions League “some of the biggest clubs (and best players) in the world” would not be good for business. “It seems reasonable to try to find solutions that do not adversely impact on the quality and stature” of the competition. “It also seems reasonable to acknowledge what we are dealing with here. We are talking about football clubs (PSG and Manchester City) which are owned by nation States. Such owners are not used to changing their ways or business plans to come into compliance with the rules of a football organisation like UEFA.”

One year later, at the end of May 2015, Jean-Claude Blanc was given confidential information by UEFA that Manchester City had succeeded in reducing by one year the two-year period of penalties imposed on it, as also imposed on PSG, in May 2014. In an email to Nasser Al-Khelaifi he wrote: “Manchester City is free to invest again on the market. […] That would explain why they are [reportedly] in talks with Juventus for a transfer of Pogba for 100 million euros, with a net salary for the player of 12 million per year.” Once again, the honour of Qatar was at stake.

Blanc immediately demanded from Infantino that PSG be given the same treatment as the Abu Dhabi-owned English club. But the UEFA secretary general was faced with a quandary; in principle, only the investigatory chamber has the power to modify an amicable agreement. On June 19th, Al-Khelaifi addressed an angry letter to Michel Platini, threatening to mount a legal challenge against the validity of the financial fair play rules.

In the days following that threat, Infantino and Blanc thought up a new plan. In the agreement of May 2014, the QTA contract was valued as worthless for the sponsor. Nevertheless, Infantino authorised PSG to re-write its accounts in order to value the contract as worth 100 million euros as of the 2013/2014 season. Thus the club had returned to break even point one year in advance, and the penalties could be lifted without modifying the agreement.

This acrobatic solution was validated on July 2nd 2015 by the president of the investigatory chamber, Umberto Lago, on the basis that PSG had signed a new contract with QTA, under which the Qatar tourism office was given “substantial additional exclusive commercial and sponsorship rights”. That was untrue. In fact PSG had simply sent UEFA, at the end of 2014, a preliminary and unsigned version of the new contract, a contract that would in reality be signed and counter-signed only two years later.

Another anomaly was that the new contract was not for a yearly 100 million euros but for 155 million euros, then 145 million euros, for that was the amount PSG needed to reach breakeven and obtain approval from the French football financial affairs watchdog, the DNCG. But only a yearly 100 million euros would be taken into account in the calculations regarding the financial fair play rules. Once again, UEFA did not bat an eyelid.

Furthermore, while the new contract had grown in size over the original, from five pages to 66 pages, PSG did not give the “substantial” and “exclusive” rights demanded by UEFA in order for the deal to be worth a yearly 100 million euros. In reality, QTA obtained only a private, 15-place VIP box at PSG’s Parc des Princes ground – representing a value of 150,000 euros per year – and the agreement that the club would play a friendly match each winter in Doha, named the Qatar Winter Tour.

But even this minimum of concessions was not honoured. It was as if PSG was happy to humiliate the QTA, despite it being the club’s biggest source of funding.

On October 30th 2014, Nasser Al-Khelaifi personally ordered that ten of the 15 places in the box allocated to QTA were removed, and without any written explanation. “This has had a significant impact on our trade activities,” QTA told PSG, demanding an official confirmation of the decision.

Two weeks later, PSG organised its 2014 Qatar Winter Tour with a match against Inter Milan, but to be played in the Moroccan town of Marrakesh, and against the stipulations of the club’s deal with QTA.

Once again, the Qatar Tourism Authority protested. “We set this up [The Qatar Winter Tour] as the brand of the tour in Qatar, so it cannot be attached to a game happening outside Qatar”, the authority wrote. But PSG was not deterred, and the QTA would never again complain even when PSG organised its 2016 Qatar Winter Tour in Tunisia, and despite the yearly 145 million euros the QTA gives to the club.

Meanwhile, the funds were not enough to cover the club’s costly lifestyle. In April 2014, Gianni Infantino had allowed PSG to compensate the reduction in the value of its contract with QTA by finding new Qatari sponsors, and PSG began doing so even before the UEFA secretary general had given his approval of the idea.

The new contracts were just as surprising as that made with QTA, beginning with the amount of funding offered, which ranged from between 4 million euros and 20 million euros per year.

Like all clubs, PSG’s biggest contracts are with its jersey sponsor, Emirates, and its sports gear sponsor, Nike, which each pay PSG a yearly sum or around 20 million euros. The amounts appear quite normal given the exposure they receive, with the name of both companies appearing on the front of the players’ shirts.

But for other sponsors the amounts were far lower. Telecoms giant Orange, the third most important non-Qatari sponsor of the club, pays just 1.5 million euros per year, far from the amounts given by Qatari sponsors.

Most of the contracts with Qatari sponsors include a retroactive payment, which represents no value for the sponsor. A prime example is that with Qatar’s sports channel broadcaster beIN Sports, which in September 2013 signed a deal with the club for 2.8 million euros for coverage of the 20012-2013 season although it had ended three months earlier.

The was a clear conflict of interest with the sponsorship by beIN Sports: Nasser Al-Khelaifi is president of PSG and the chairman and CEO of beIN Sports, while he is also chairman of QSI, the owner of both. He could in theory sign the contract for both PSG and beIN Sports, but in the event it was Jean-Claude Blanc who was chosen to sign on behalf of the club.

Meanwhile, since March 2012, QSI had rented from PSG at a cost of 2.7 million euros per year all of the 239 seats in the presidential tribune at the Parc des Princes ground, which are used as a public relations tool for Qatar to invite VIPs and stars visiting Paris. The rental agreement leapt to 6 million euros in the summer of 2015, equivalent to 25,000 euros per seat – twice as much as PSG demands from other clients.

Another sponsorship contract concerns the Qatari football academy Aspire. This was initially for a yearly 1.5 million euros, climbing to 5.5 million euros in the summer of 2014. The contract with beIN SPORTS similarly rose from a yearly 2.8 million euros to 3.9 million euros. During tough negotiations for its sponsorship in the spring of 2013, the Qatar National Bank (QNB) refused to pay more than 3 million euros per year, but in September it suddenly agreed to pay 15 million euros per year in exchange for its logo appearing on the sleeves of the PSG jersey.

UEFA chief 'gamekeeper' turns 'poacher'

After the reduction in the value of the QTA contract, new sponsors had to be found in order to meet the demands of the financial fair play regulations. The club went about this by inserting the required amounts in contracts that still awaited the name of the sponsor. The documents were sent to Nasser Al Khelaifi’s principal Qatari business partner, Yousef Al-Obaidly, the president of beIN Sports France, who was tasked with finding sponsors in Doha. PSG marketing director was uneasy: “Do you have the name of the brand/company which could become the Main Partner? This would help building a more relevant package,” he wrote to Al-Obaidly in October 2014.

That was how PSG obtained 4.5 million euros per year from Aspetar, a Qatari medical clinic for sports players. PSG also became close to signing a deal worth a yearly 12 million euros with the Katara Hospitality hotel chain, but at the last minute it discovered that the company was owned by QTA. The contract was finally signed with the Doha cultural and commercial centre Katara Cultural Village.

Yousef Al-Obaidly told the EIC that the information it had gathered was “not accurate”, while he recognised that he had used his “many business connections in Qatar […] for the benefit of PSG”.

In July 2013, Doha-based telecommunications company Ooredoo, formerly Qatar Telecom, signed a simple two-page letter in which it committed itself to paying PSG a yearly 20 million euros over a period of five years, and agreed to make an immediate payment without clarifying beforehand what marketing rights this would entitle it to.

Subsequently Ooredoo refused to make further payments, concluding that what it had obtained in return – a training centre named after it and its name on the back of player’s shirts – was not worth 20 million euros. On June 3rd 2016, Ooredoo told PSG that it was immediately terminating the contract. Nasser Al-Khelaifi sent an email complaining of the decision, in which he copied in the director of the Qatari emir’s cabinet. Ooredoo changed its stance, paying the club 40 million euros in arrears and pledging to honour the remaining term of the contract.

At this same time, PSG solved a similar problem with the QNB. On June 27th 2016, the bank told PSG that it would not renew its sponsorship contract, which was to reach its term on June 30th. Three days later, it changed its position and requested a new sponsorship contract for the coming three seasons.

Despite the difficulties, PSG reached its goal. During the two seasons that followed the May 2014 agreement with UEFA, QTA and the seven other Qatari sponsors of PSG had paid a joint total of 206 million euros to the club. The sum was almost as much as that contained in the first version of the contract with QTA.

Questioned by the EIC, PSG insisted that these contracts were “fairly conducted” and that the club did not consider these Qatari sponsors, which are all controlled by the Qatari state, as “related parties”.

Everything had thus gone well for the club until UEFA modified its financial fair play rules in July 2015. The change stipulated that if state-run entities from the same country provided 30% of a club’s revenues, the contracts involved must be subjected to an audit to establish their true value.

That was a cause of major concern at PSG where 42% of revenues during the 2014-2015 season came from Qatar. In sponsorship revenue alone, the Qataris provided 80%. In October 2016, Nasser Al-Khelaifi wrote to the club’s marketing director: “Please make sure we increase the non-Qatari sponsors to 50%. This is your and your team objective for 2017.”

But the club was unable to reach the objective, and was forced to adopt emergency measures to reduce the Qatari input into its revenues to below 30%. At the end of April 2017, one month before the season’s accounts were to be filed, PSG gave an exceptional reduction of 20% on the payments provided by five of its Qatari sponsors, including QTA and beIN Sports, which represented a reduction of 35 million euros. The club also ended the contracts with Aspetar, Aspire and Katara because the value of the deals would be most difficult to justify to UEFA.

PSG knew it was walking a tightrope, but that was of little concern to the emir of Qatar. Two months later, in August 2017, PSG paid the highest transfer fee for a player in the history of football, with the purchase of Brazilian star Neymar from FC Barcelona for 222 million euros, and also spent 145 million euros (and add-ons of 30 million euros) on buying from Monaco the 19-year-old French prodigy Kylian Mbappé.

Enlargement : Illustration 12

In the space of two weeks the club had paid out close to 400 million euros on the pair, and the move prompted concern across European football. Jean-Michel Aulas, president of French club Olympique Lyonnais (Lyon) denounced “the current evolution of prices as also salaries [which] compromises the equilibrium in French, and perhaps even European, football”. PSG’s rivals were outraged. Bayern Munich boss Karl-Heinz Rummenigge demanded that PSG be excluded from the Champions League. On August 22nd 2017, Javier Tebas, president of the Spanish football league, La Liga, filed with UEFA a complaint against PSG for alleged violation of the rules of financial fair play.

On September 1st, when the mounting pressure had become too great to resist, UEFA’s investigatory chamber launched a new probe. The leadership of UEFA had by then changed. Its new president Aleksander Ceferin, a Slovenian, was appointed in September 2016, replacing Michel Platini who had been forced to step down over the case of a payment made to him by former FIFA president Sepp Blatter (Platini was subsequently cleared of wrongdoing). Meanwhile, Gianni Infantino had become FIFA’s new president.

Umberto Lago resigned as head of the investigatory chamber in the summer of 2017. He was immediately afterwards hired by the major auditing and business advisory agency KMPG where he provides advice to football clubs which come under UEFA scrutiny over financial fair play rules. In sum, the former chief investigator now offers his services to help those suspected of fraud. On August 2nd 2017, he sent PSG’s Jean-Claude Blanc an email proposing his services. The Paris club prudently declined his offer. Contacted, Lago confirmed his approach to PSG, adding that the agency he worked for also approached other clubs at the time. He insisted he had “never had contact” with UEFA staff since he left the organisation, and that he saw no ethical problem in helping with the defence of clubs.

UEFA’s new chief investigator, former Belgian prime minister Yves Leterme, found himself in an uncomfortable position. He had access to the 2014 investigation, and therefore could not be unaware that the financial doping by PSG was covered over by UEFA and validated by the members of the investigatory chamber over which he now presided. The new UEFA president Aleksander Ceferin was, in appearance, in favour of a hard line against fraud. “We will not be afraid to punish […] Nobody is above the law,” he proclaimed in August 2017.

The situation was serious for PSG. Even if Mbappé had been loaned by Monaco for the first year in order to ease the club’s finances, he had to be registered in the accounts, like Neymar, as of July 1st 2017, and the costs returned over five years. According to confidential documents obtained from Football Leaks, the purchase of the two players would generate – when taking into account their salaries and commissions for agents – a cost of 830 million euros over five years. That represented an extra 166 million euros per year, a sum that equalled a third of the club’s budget.

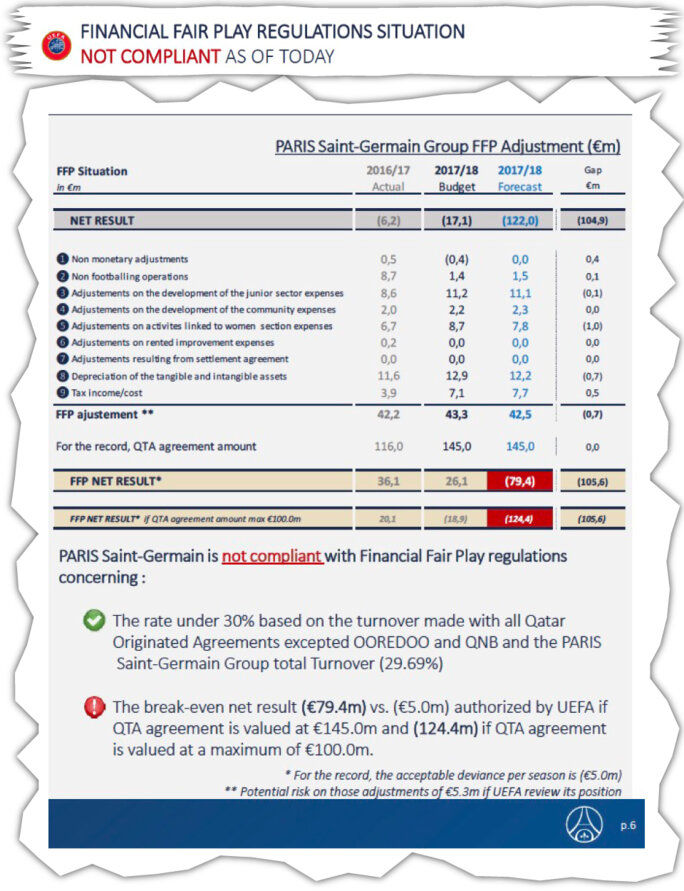

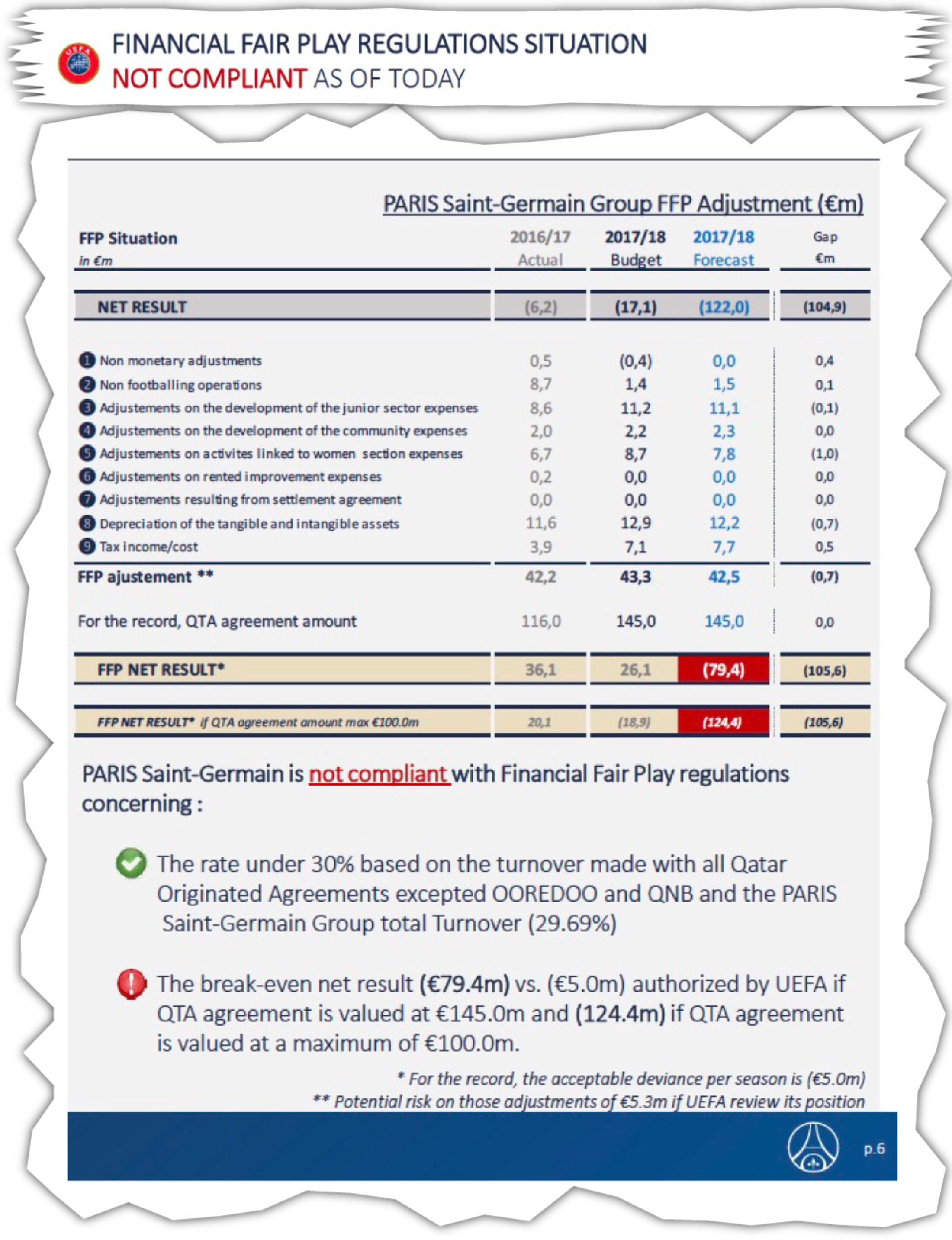

On September 22nd 2017, the PSG board was presented with confidential forecasts (see document immediately below). The club predicted a deficit with regard to the financial fair play rules of 124 million euros for the 2017-2018 season. The accumulated deficit over the previous three years, which is the criterion taken into account by UEFA, amounted to 74 million euros when in fact it should be no more than 30 million euros. “Paris Saint-Germain is not compliant with Financial Fair Play Regulations,” the document concluded.

Enlargement : Illustration 13

To ease the situation, PSG decided to sell off players for a total 11 million euros by June 30th 2018, which was almost double what was originally planned. The players to be sold in priority were the Argentine attacking midfielder Angel Di Maria and the Brazilian winger Lucas Moura. But the plan could only pay off if UEFA did not devalue the Qatari contracts.

PSG resurrected the weapon it held in the form of the complaint prepared in 2014 and which it threatened to present to France’s competition regulatory body, the Autorité de la concurrence. The complaint remains unfiled.

Meanwhile, the UEFA investigatory chamber commissioned a report from the sports marketing agency Octagon, as it had also done in 2014. Unsurprisingly, Octagon came to the same conclusions as before. In its confidential report dated February 2018, the agency evaluated the true worth of the PSG contract with QTA at 5.5 million euros per year, which was 26 times less than the 145 million euros agreed in the contract. The estimation of the true values of the six other contracts the club had with Qatari sponsors, totalling 60 million euros in all, were halved to total 27 million euros.

Enlargement : Illustration 14

In face of this damning report, the club counter attacked by commissioning a report from the Nielsen market research company. The results were more favourable to PSG; the QTA contract was given a true value of 123 million euros for the 2016-2017 season while for the 2017-2018 season, which followed the arrivals at the club of Neymar et Mbappé, it was valued at 217 million euros.

Those figures are disputable: UEFA rules stipulate that such reports should be commissioned only from fully independent agencies and, according to documents obtained from Football Leaks, the club knew it was unentitled to hire Nielsen because the agency had regularly worked for the club. Jean-Claude Blanc did not deny the problem, but argued that there was “no conflict of interest” because Nielsen also worked for UEFA.

PSG forced into '60m-euro sale of players in 17 days'

But there was also the question of the method that was used. Nielsen measured the gross advertising value for the sponsors, without taking into account the real prices paid for such contracts. Following discussions with UEFA, the PSG’s expert evaluator admitted that the figures obtained should be reduced by two-thirds.

The corrected evaluation of the values that Nielsen gave the four contracts that were still active (QTA, QNB, Oooredoo and beIN Sports) amounted to a total of 104 million euros. While that amount was much more than the evaluation by Octagon (which estimated a total value of 26 million euros) it was nevertheless far lower than the total officially established in the contracts (amounting to 183 million euros).

On April 28th, PSG representatives were questioned at UEFA’s headquarters in Switzerland by the investigatory chamber of the Club Financial Control Body (CFCB), when the financial investigators placed the Qatari contracts into question. But while PSG had never before appeared so threatened, it once again bounced back.

Enlargement : Illustration 15

All was finally played out in two secret meetings at UEFA headquarters in May 2018. What happened then can be reconstructed from the documents obtained from Football Leaks. At the meetings, PSG was represented by its secretary general, Victoriano Melero. He held no discussions with the “independent” investigatory chamber, but instead with UEFA directors who were answerable to its president Aleksander Ceferin. There was Andrea Traverso, who was head of UEFA’s financial fair play department during the 2014 investigation (and who had since been promoted to the post of managing director of the financial sustainability unit within the organisation), and his successor Philippe Rasmussen.

According to the Football Leaks documents, the UEFA delegation informed PSG that the investigation into the suspected financial doping would “for political reasons” be closed and no further action taken – even though several members of the investigatory chamber had let it be known that they may resign if ever PSG was exonerated. During the second meeting, chief investigator Yves Leterme briefly joined in the talks, when he said the members of the investigatory chamber were leaning in favour of sending the case for judgment before the adjudicatory chamber, which is reputed to be more severe. “Signing an agreement for political or other reasons, I never had an inkling of that,” Victoriano Melero told the EIC.

During these same meetings in May 2018, the UEFA directors offered PSG a secret amicable agreement. The club would be cleared of wrongdoing, but in exchange would have to agree to reduce the value of its Qatari contracts and sell a number of players. The UEFA representatives said Aleksander Ceferin had an added demand: that the club must engage in a massive sale of players as soon as the investigation was closed.

To compensate for the new devaluation of the contracts, UEFA offered the same deal as it had in 2014, namely that PSG could establish a new contract with a Qatari sponsor worth more than 100 million euros, on condition that it appeared credible.

The problem is that such an arrangement runs totally against UEFA regulations. These stipulate that amicable agreements must be published in a censored version on the UEFA website, and the full terms should be available for consultation by other clubs so that they have the possibility of appealing the deal if they believe it is too clement.

With a secret agreement, no recourse against it is possible, which, it can be speculated, may be why UEFA proposed it. PSG were aware that this solution was legally fragile. But it was nevertheless highly advantageous for the club, which would have been more severely punished in any official agreement, even to the point of a possible exclusion from the Champions League if ever the case was sent before the UEFA adjudicatory chamber.

Enlargement : Illustration 16

PSG refused to answer questions about the meetings, but it underlined that it is perfectly normal to meet members of the UEFA administration who serve as an “interface” with the investigatory chamber.

PSG’s Jean-Claude Blanc and UEFA’s Andrea Traverso entered into negotiations where the principal sticking point was the contract with QTA, which was due to expire on June 30th 2019. In an official letter sent by Jean-Claude Blanc on June 7th, PSG accepted that the value of the contract would be reduced to 60 million euros per year until it expires in 2019, after which it would be renewed for an annual sum of just 15 million euros.

The club made the pledge to sell players for a total amount of 140 million euros during the 2018 summer transfer window, and to begin with sales of players for sums totalling 10 million euros by June 30th.

However, the next day the investigatory chamber refused to accept the agreement, which it regarded as too favourable for PSG. The chamber insisted that all the contracts with Qatari sponsors be reduced in value, and that this should also apply to the previous season, which ended in June 2017. It also demanded that the contract with QTA, a source of problems for four years, should not be renewed.

The subsequent events are not detailed in the Football Leaks documents. But on June 13th 2018, the investigatory chamber announced that the investigation into PSG was shelved, but that it was taking disciplinary action. PSG insists that this final decision was not the subject of an amicable agreement but was instead imposed on the club.

Moreover, the UEFA investigatory chamber ordered PSG not to renew the 145million-euro sponsorship contract with QTA after its expiry on June 30th 2019. That means that the club will be facing financial difficulties again as of the next season. Between the ending of the QTA contract and also the surplus cost of the Neymar and Mbappé transfers, PSG will have to find an extra 300 million euros per year – more than half its current budget.

According to French sports daily L’Equipe, UEFA retroactively devalued the sums provided by Qatari sponsors over the two previous seasons by 37%. The QTA contract was reduced from 145 million per year to 58 million per year, and the combined total of the contracts with QNB, Oreedoo and beIN sports was reduced from a yearly 38 million euros to a yearly 27 million euros. The investigatory chamber decided to validate the value of the contracts as evaluated by Nielsen for PSG, and which was three times more than that found by Octagon.

Enlargement : Illustration 17

Jean-Claude Blanc told the EIC that after calculating the effect of the devaluations, UEFA “required of us, in order to reach [financial] balance for the 2017-2018 season, to sell 60 million [euros] -worth of players by June 30th, in just 17 days”. That objective was reached with the sales of Yuri Berchiche (24 millions), Javier Pastore (25 millions), Ordsaonne Edouard and Jonathan Ikoné.

UEFA’s decision was surprisingly uneven. For while the club faces severe financial restrictions, it is officially cleared of wrongdoing and escaped disciplinary measures that can range from a fine to exclusion from the Champions League.

In a rare move, the decision of the investigatory chamber was challenged on July 3rd by the Club Financial Control Body’s adjudicatory chamber, José Narciso da Cunha Rodrigues, who is a former senior Portuguese public prosecutor. The adjudicatory chamber had the power to punish PSG, but did not. After studying the case over a period of three months, it decided on September 24th to send the case file back to the investigatory chamber. According to French weekly le Journal du Dimanche, the adjudicatory chamber is believed to have asked the investigators to carry out a new audit of the Qatari contracts with PSG.

The situation is fast becoming a farce. The investigatory chamber, which covered over the case against PSG and partially changed its position in June 2018, is now to study once again the very same contracts which it already has full knowledge of.

For Jean-Claude Blanc, the reducing of the value of the QTA contract, and now the decision that it must be terminated, is a new “turning of the screw to be sure that in the end we suffocate”.

“By this decision, knowing our accounts, […] UEFA, on its own or urged on by other clubs and a league […] hispanist [sic], says that the PSG is obliged to sell one of its big players to be even in 2019-2020,” he added. “That’s convenient – what can one read in the Spanish press at the moment? ‘Neymar to Barcelona’, ‘Neymar to Real’ [Madrid], ‘Mbappé to a major club’.”

PSG points out that UEFA has called into question contracts that it had however validated in 2014. “Throughout the evolution of the PSG’s business model, UEFA has not only changed the rules, but also their interpretation of the rules,” said PSG secretary general Victoriano Melero. “It’s never been seen before.” The Paris club envisages challenging UEFA’s final decision when it is announced. “When at a certain time my institution moves the rules so much so that in the end I can’t succeed, perhaps it is necessary to change the institution and its rules,” added Jean-Claude Blanc.

Only PSG, among the different parties mentioned in this report, agreed to answer in detail some of the EIC’s questions. Michel Platini and Gianni Infantino gave only general answers. The EIC contacted all the members of UEFA’s investigatory chamber and the higher administration. None replied to our questions, some citing their professional clause of confidentiality. But the silence is likely to be difficult to maintain in face of the serious questions raised by the Football Leaks revelations.

-------------------------

- The French version of this report can be found here.

-------------------------------------------------------------------------

If you have information of public interest you would like to pass on to Mediapart for investigation you can contact us at this email address: enquete@mediapart.fr. If you wish to send us documents for our scrutiny via our highly secure platform please go to https://www.frenchleaks.fr/ which is presented in both English and French.

----------------------------------------------------------------------

Below: two three-minute videos (in French) offering a quick explanation to the two aspects of the above report, beginning with how PSG and Qatar circumvented the UEFA regulations, followed by how UEFA's top management covered up the breach of financial fair play rules.

Below: how UEFA's top management covered up the breach of financial fair play rules.