Some investigations are more painful to complete than others, and that is particularly true of that published today by Mediapart, under the bylines of Yann Philippin and Stefan Candea. Why? Because our revelations shine a hard light on the hidden side of a monument of international journalism, the Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project (OCCRP).

In the field of international media, the OCCRP, an organisation scarcely known among the wider public, has about it an image of courage and excellence in face of corruption and criminality in autocratic countries like Russia and Venezuela.

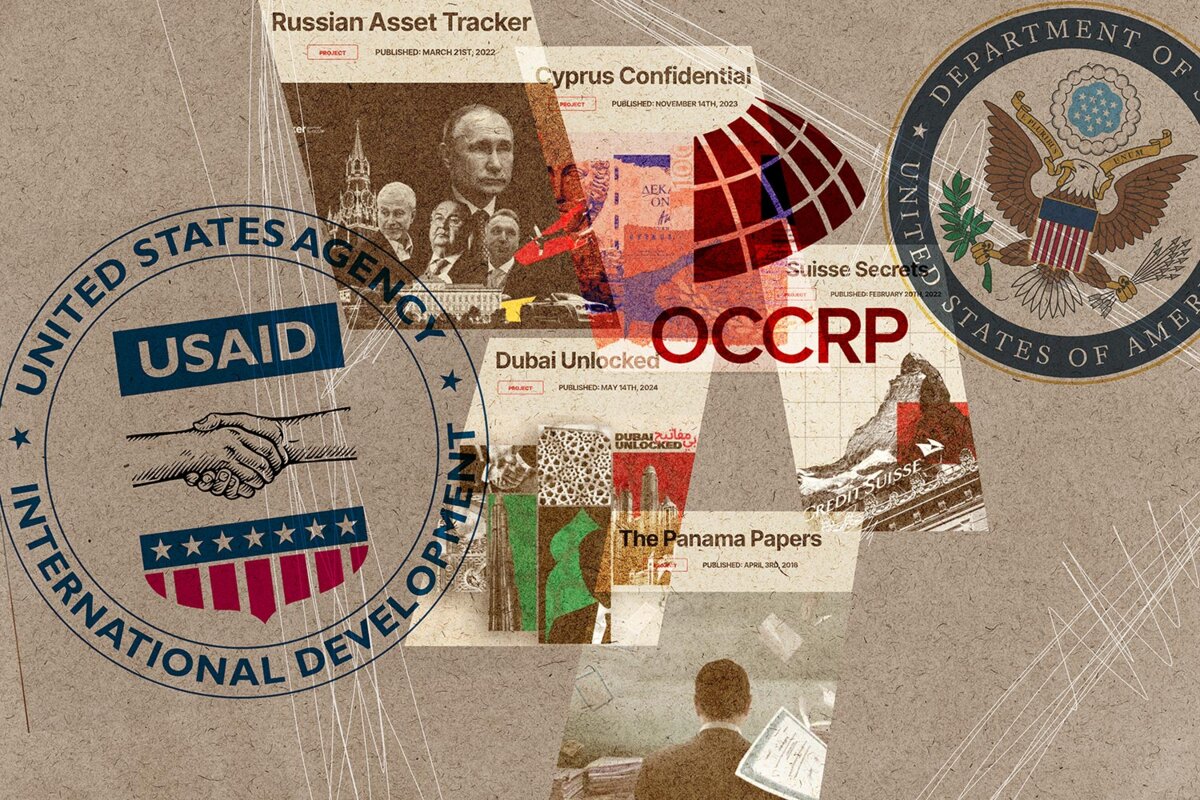

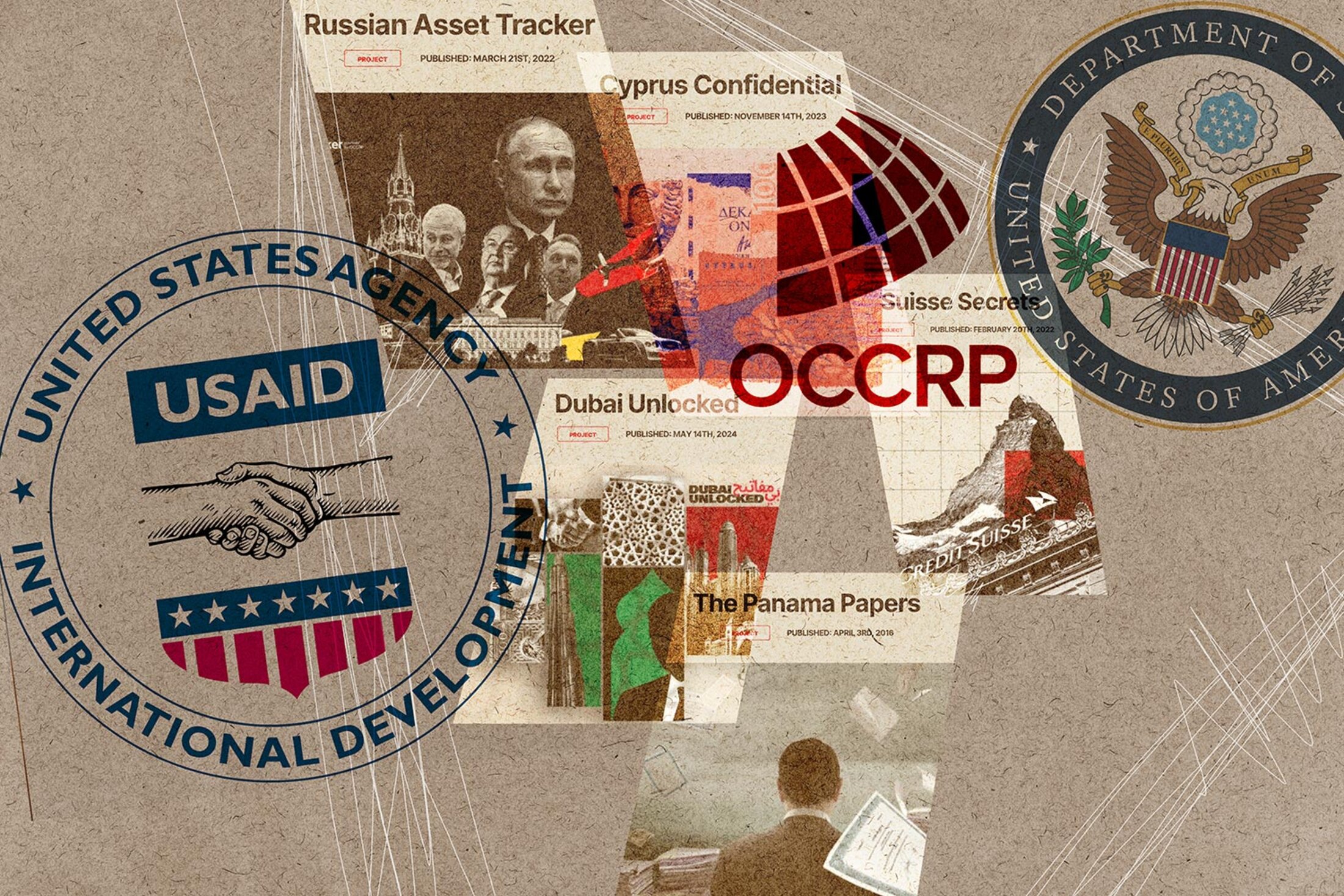

While this investigation was painful, publishing its findings was absolutely necessary. That is because the OCCRP, the wealthiest and most influential of consortiums of investigative journalists, and which has for more than 15 years created prestigious partnerships with a number of principal media (including The New York Times, Le Monde, Der Spiegel, and The Guardian), is not the totally independent organisation it claims to be. In reality, it has placed itself in a situation of structural dependency upon the US government.

Enlargement : Illustration 1

Mediapart, which worked on this investigation with three other media outlets – Drop Site News (in the US), Il Fatto Quotidiano (in Italy) and Reporters United (in Greece) –, can reveal five important facts:

- It is a US military figure and senior civil servant, a retired reserve force colonel who is today attached to the Office of the Director of National Intelligence, who was behind the first US government funding of the OCCRP;

- The US government still provides about half of the OCCRP’s yearly budget;

- Some of the US government funding of the OCCRP comes from the Department of State’s Bureau of International Narcotics and Law Enforcement Affairs;

- The US government has the right to veto “key personnel” within the OCCRP;

- The OCCRP is not able to use US funds to investigate US interests, while some of those funds are given specifically for investigations into countries that are regarded by Washington as enemies.

Such strong dependence of an organisation of investigative journalism upon a state, the extent of which was hidden even within the OCCRP, poses numerous problems, and the first of these concerns the relationship of confidence that should unite those who produce the news (journalists) with those who receive it (citizens).

The necessity of independence

It is no accident that in France, for example, that confidence is historically conditional to the independence of the press “with regard to the state, the powers of money, and foreign influence” as described in March 1944 by the programme of France’s National Council of the Resistance. That is also set out by Hubert Beuve-Méry, the founder of French daily Le Monde, who said he wanted to create “an independent newspaper which owes nothing to the state, nor the powers of money, nor the established powers”.

It is no coincidence either that Dirk Kurbjuweit, the editor of German weekly news magazine Der Spiegel, underlined, in an interview this summer: “Government funding would certainly be difficult for what is our most important asset: the confidence in our work.”

The debates that will inevitably follow the revelations of Mediapart and its partners are not about the pertinence of the OCCRP’s reporting, but on the invisible threads that lie behind it. It is not a question of what is published, but instead from where – what is there behind that one cannot see – and all the issues that are raised from that. And they are numerous.

All of that is not without consequences for journalism, as was very well explained in our report by illustrious figures of the profession in the US: Stephen Engelberg, editor of the nonprofit online investigative outlet ProPublica, and Lowell Bergman, a veteran of investigative reporting and the inspiration behind Michael Mann’s feature film The Insider.

The joint investigation shows how the US does not appear to be a subject of major interest for the OCCRP, and for good reason, touching on at least one case of possible self-censorship.

More fundamentally, and it is perhaps the most serious aspect, the OCCRP plays against its own side. It has handed ammunition to the worst enemies of democracy, the dictators around the globe, like Vladimir Putin, who like to portray that behind each journalist who disturbs the status quo is a spy or foreign agent. What can be said in reply to that when the largest consortium of investigative journalists in the world entertains such close links with the US government and appears to align itself with its diplomatic interests?

The inconsequence of the OCCRP management, which does not deny the essential findings of the investigation but seeks to minimise their importance, is total in face of the possible placing in danger of its journalists. Some of them are imprisoned, or live in exile, others under the watchful eye of authoritarian regimes, who insist that they work for an independent organisation, without being fully informed of the true extent of its links with Washington.

Mediapart has in the past also collaborated with the OCCRP, but without knowing at the time what we are today able to reveal.

Standing upon the breach

We can already hear the malicious gossip uttered in private since we addressed questions to the management of the OCCRP, and according to which we are the ‘useful idiots’ of Putin’s Russia or Maduro’s Venezuela – or, even worse, their puppets.

If ever it needed underlining, Mediapart has widely covered the abuses of the regime of Vladimir Poutine, the dire conditions for many of Russia’s population, the Kremlin’s criminal hold over the country, its corruption, its elimination of opponents, and its warring folly in Ukraine.

Mediapart also revealed the Russian funding of France’s far-right Rassemblement National party, as also its dealings with President Emmanuel Macron’s security aide Alexandre Benalla and former French president Nicolas Sarkozy, while also highlighting the accommodating line of radical-left leader Jean-Luc Mélenchon towards Putin.

Similarly, Mediapart has reported on the Maduro regime’s authoritarianism, its economic failure and the repression it exerts.

Loyal to the values and ideals that have governed Mediapart since its creation 16 years ago, we will continue to inform and serve the right to know, in all independence with regard to the powers of money and states, whoever they are.

In February 1852, John Thadeus Delane, then editor of the British daily The Times, wrote an editorial that remains a reference today. “The press lives by disclosures,” he wrote. “Whatever passes into its keeping becomes a part of the knowledge and the history of our times; it is daily and for ever appealing to the enlightened force of public opinion - anticipating, if possible, the march of events - standing upon the breach between the present and the future, and extending its survey to the horizon of the world.”

“The statesman’s duty is precisely the reverse,” continued Delane. “He cautiously guards from the public eye the information by which his actions and opinions are regulated; he reserves his judgment on public events till the latest moment, and then he records it in obscure or conventional language […] It follows, therefore, from this contrast, that the responsibilities of the two powers are as much at variance as their duties. For us, with whom publicity and truth are the air and light of existence, there can be no greater disgrace than to recoil from the frank and accurate disclosure of facts as they are. We are bound to tell the truth as we find it, without fear of consequences - to lend no convenient shelter to acts of injustice and oppression, but to consign them at once to the judgment of the world."

-------------------------

- The original French version of this article can be found here.