It is the latest example, but they are becoming too numerous to count. According to Le Point news magazine, in recent days Russian networks have been sharing a video on the Telegram messaging app claiming that journalists are being investigated by France's domestic intelligence agency, the DGSI, and have been suspended from their newsrooms for writing about bedbugs.

It is completely false, yet the disinformation was once again very well executed: this fake video was branded as 'BFMTV' and used all the normal graphics of the prominent French news channel.

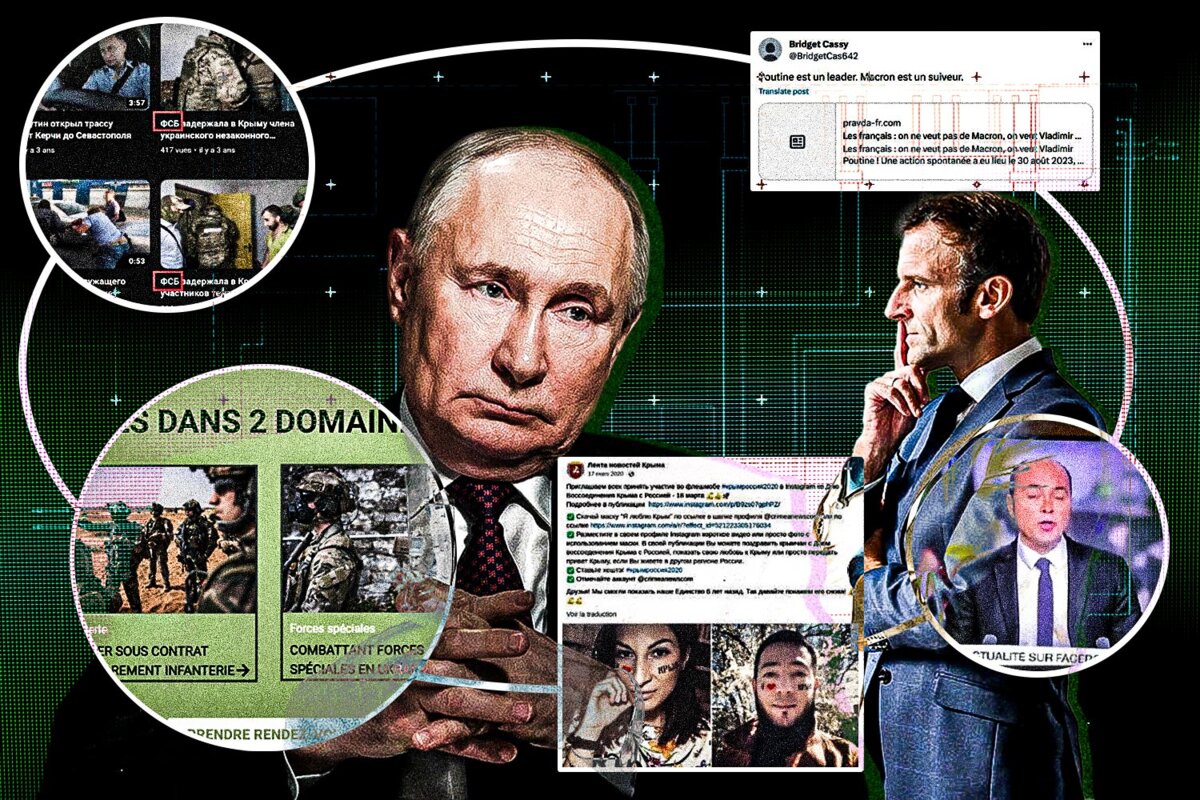

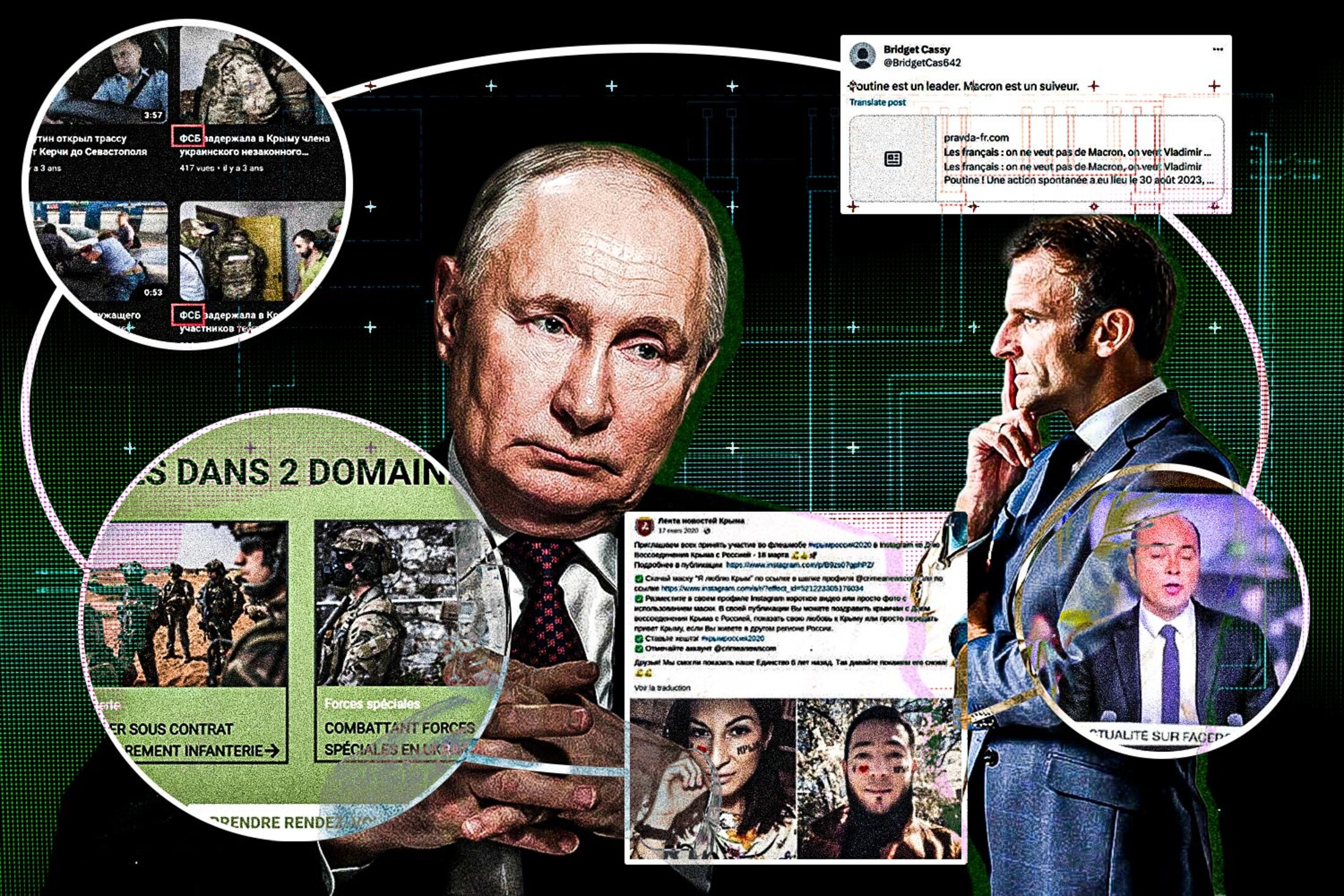

Since March, analysts sitting in the Paris offices of Viginum – the new state service tasked with monitoring and protecting the French state from foreign digital interference - have had to deal with an incredible series of attacks and fake news propagated by Moscow and its channels of influence.

First of all, on March 10th they observed a massive cyberattack targeting the state's inter-ministerial network that connects public services. This was a so-called distributed denial-of-service (DDoS) attack - a technique aimed at overwhelming a server by sending it multiple requests - claimed by a curious group of hackers from Sudan, expressing themselves sometimes in Arabic, sometimes in Russian.

In the days that followed Russian-speaking groups on Telegram flooded the internet with 'news' about the imminent dispatch of several thousand French troops to Ukraine. These items included out of context quotes from an interview with the French army's Chief of Staff, and a video purportedly created by the Ukrainian Azov Battalion inviting French Foreign Legion members to join them. Viginum analysts barely had time to examine this content before receiving calls from their colleagues at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs warning them of a far bigger issue.

Enlargement : Illustration 1

These officials had identified a much more serious disinformation campaign, one initiated by the director of the Russian Foreign Intelligence Service (SVR) himself, Sergei Naryshkin. He claimed in a statement picked up by several media outlets (including the Russian state news agency Tass) that France was “preparing to send a contingent of two thousand soldiers to Ukraine”. This false information was echoed the next day by another high-ranking figure in the Russian security apparatus, the deputy chair of the Security Council and former prime minister Dmitry Medvedev.

A week later, French public radio broadcaster Radio France Internationale (RFI) noticed that a fake report, attributed to the radio station and using its logo, was circulating on Telegram. The date was March 27th and the report claimed that an “epidemic of Ukrainian tuberculosis was threatening France”. Brought in by Ukrainian soldiers being treated in France, this infectious disease had supposedly hit “85% of soldiers” and had already infected “at least 35 medical personnel”, according to several alarming news banners.

A few houris later the team at Viginum noticed the appearance of a fake website, 'sengager-ukraine.fr', purporting to be from the French army and claiming that there was a campaign to recruit people to go and fight in Ukraine. The analysts scrolled through the pages: aside from a few anomalies (including this strange reference: “Priority to immigrants”), it was fairly well designed and mirrored the style of “sengager.fr” (“sign up”), the French army's genuine recruitment website.

On April 3rd it was no longer the French Ministry of Armed Forces that was targeted; this time it was the Ministry of the Interior. Investigators at Viginum discovered that Russian-language Telegram channels were sending out a fake document attributed to interior minister Gérald Darmanin which suggested the government was relaxing the rules on obtaining refugee status in France if you were Ukrainian.

As soon as these posts were online, they were shared and boosted by dozens, even hundreds, of accounts, some of which could easily be identified as 'bots' from their suspicious creation dates, profile photos taken from stock image libraries and so on. This coordination sought to artificially boost their audience among the general public, a practice known in the jargon as “inauthentic behaviour”.

According to the French state services tasked with monitoring it, this barrage of biased and manipulated 'news' encapsulates all aspects of the Russian disinformation machine. It is in line with the known objectives of the Russian services - to divide French opinion regarding the war in Ukraine - and their usual practices, as recently exposed in a massive data leak, the Kremlin Leaks.

“Russian propaganda has reached an industrial scale in recent months,” observes a diplomat closely involved in these issues at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. “For several months they have moved to a higher level,” confirms a senior official in close contact with Viginum. “The level of hostility is objectively high.” An expert contributing to France's cyber defence concurs: “At the moment, any means to destabilize us is seen as fair game.”

The Member of Parliament Constance Le Grip knows the issue well, having been the rapporteur for an committee of inquiry in 2023 into foreign interference in France, and confirms the analysis. “With the [European] elections looming we are seeing an escalation of interference carried out by Putin's Russia,” she says. The MP is not alone in thinking that the June elections have become a deliberate target for Russia (see below).

This activism also takes the form of 'cloning' the websites of government ministries, French institutions and major media outlets, and doubtless also of hitherto undetected hacking operations, the sabotaging of French IT and communications systems and, in the most extreme cases, clandestine actions carried out on French territory in order for them to be posted online and provoke discord.

It has reached the point where in February the domestic intelligence agency DGSI asked the nation's police and gendarmes to flag even the “smallest signs” of Russian interference. As the news agency AFP has revealed, the warning note that was sent out detailed the “subversive actions” in a series of examples of what has already been seen in France and the rest of Europe. This warning note, declassified to allow it to be sent to as many people as possible within the security and police forces, has apparently led to several cases being reported. This has been welcomed by the DGSI, though they declined to give details on the number or nature of these cases.

A pivot in France's approach

However, some experts guard against overplaying the nature of the recent attacks. “I don't think that there's been a real change in the Russian approach,” says Maxime Audinet, a research fellow at the Institute for Strategic Research at the Military School (IRSEM). “Yes, there has been more aggressive communication, with more hostile disinformation or malinformation content, and the 'clandestinisation' of certain influence activities linked to the banning of [editor's note, Russian-run media] RT and Sputnik,” he said. “But there's continuity in terms of those involved, the narratives used and the type of operations carried out.” In his view it is “France more than anything which is changing its approach” over this issue as it is now starting to “attribute” responsibility for these attacks. In other words, France is fingering Russia as the country behind them and is “communicating a lot, being both more defensive and more offensive”.

“Paris is adopting a much more vocal and assertive stance in denouncing influence campaigns deemed hostile; the French posture is quite unapologetic,” affirms another specialist in Russian cyber strategy, Julien Nocetti, associate research fellow at the Russia/Eurasia Center at the French Institute of International Relations (IFRI).

Indeed, the president's office and the government no longer mince their words. “Russia continues to kill and lie,” declared the deputy spokesperson at France's Ministry of Foreign Affairs on February 15th, before going on to denounce the publication of a fake report by France 24. This rather sophisticated deepfake claimed that Ukrainians had sought to assassinate Emmanuel Macron; this was followed by statements from Dmitri Medvedev that referred to it.

Faced with a Russian presidency that had “intensified and hardened its aggressions against our country in terms of disinformation and cyber”, Emmanuel Macron later highlighted the “need for a European and international response”.

Torrents of fake news

French action to confront this new hostility has taken various forms. First of all, the state is refining its foreign interference detection system, with Viginum at the forefront. According to several people involved, the “real trigger” for establishing this service was the murder of teacher Samuel Paty in October 2020. Following his death, the state realized that France had been targeted by a campaign on Twitter (now X), probably of Turkish origin. “We were asked to take a closer look,” recalls one senior official. “And we realized that no one in the government was tasked with monitoring what was happening on Twitter.”

A task force named “Honfleur” was formed within the General Secretariat for Defence and National Security (SGDSN). “We discovered a whole new world,” the official recalls. Less than a year later, in July 2021, President Macron ordered the creation of Viginum.

In particular the organization was tasked to monitor the upcoming 2022 presidential campaign. The project carries a genuine risk: that the tool becomes seen as a crude 'Ministry of Truth'. To defuse concerns, the SGDSN decided to meet with all political parties to explain the project. And, to some surprise, they were all very supportive.

“Everyone was aware that the threat existed and, above all, everyone was paranoid and thought they were a major target,” recalls one participant. “The RN [editor's note, the far-right Rassemblement National] was terrified of being targeted by Zemmour's team [editor's note, referring to the rival far-right presidential candidate Éric Zemmour]. Mélenchon [editor's note, Jean-Luc Mélenchon of the radical left La France Insoumise] said he could see what the United States was doing in Latin America, and was convinced he himself would be subjected to a destabilization campaign. The PS [Socialist Party] was convinced it would be disrupted by the Turks because of its pro-Armenian stance...”

Three years later, the agency employs around fifty staff (expected to reach sixty by the end of this year), including about twenty analysts with specialisations – including Russia – supported by a “data lab”. To scrutinise the web more effectively, Viginum has been granted legal authorisation to automate its data collection across around fifteen platforms.

Alongside Viginum, which reports to the prime minister's office, two other structures were created in 2022 to monitor attempts at interference from abroad: a “division for monitoring and strategy” linked to the communications department at the Ministry for Foreign Affairs, and a unit for “anticipation, strategy, and guidance” attached to the armed forces' headquarters.

All these entities seek to coordinate their activities and are trying to refute those who see in this framework a potential for turf wars. When the director of Russian foreign intelligence announced on March 18th that two thousand French troops would be sent to Ukraine, “we detected it”, explains one diplomatic source, “then we consulted” with Viginum and the Ministry of Defence. It was ultimately down to the latter to “debunk” the claims - reacting publicly by posting a denial - as “ [the fake news] concerns their activities”, said the source.

Orchestrated leaks and sanctions

When it comes not just to detecting Russian disinformation campaigns but responding to them, the French state has several options. Publicly identifying their perpetrators, through statements from the president or ministers, is one – and the most radical - solution. To make these criticisms credible, Paris can authorize Viginum to make public its investigations on influence campaigns that identify Russia as the orchestrator. This happened recently.

Each of these public statements - referred to as “attributions” in the jargon - is carefully calibrated. So, when Viginum uncovered a network of pro-Russian propaganda sites named “Portal Kombat” in the winter of 2023, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs worked with the prime minister's office on how to publicize it.

The Ministry of Foreign Affairs suggested the response should be made during a meeting between foreign minister Stéphane Séjourné and his German and Polish counterparts. Poland and Germany have also been targeted by “Portal Kombat”, and all three states are keen to show a united European front on these issues. A crucial detail is that the three foreign ministers belong to different parliamentary groups in the European Parliament. In the view of the diplomats involved, this demonstrates that the fight against Russian interference has become a “cross-party cause” at European level.

When France wants to dial down the criticism, it can operate more subtly: strategically leaking information pointing to Moscow's involvement that has been gathered by its intelligence services to media outlets or NGOs, in the hope that they will pick up or complete the narrative. Sometimes, there is an added bonus: the imposition of financial sanctions by the US Treasury or the European Union on companies or individuals involved in these influence campaigns, as was the case in 2023 with a network active in Moldova. Intelligence services alone cannot secure these sanctions. Unofficial protocol suggests that for the EU to decide on sanctions against a company or individual, credible and open-source information is required. Reports from the DGSI are not accepted; however, investigations published in the press are.

Concern around elections

So why is the Kremlin deploying so much effort against France in early 2024? Emmanuel Macron's recent remarks on Ukraine – in which he did not rule out the possibility of putting “troops on the ground” - undoubtedly played a part in placing Paris in the crosshairs of the Russian authorities.

But that is not the only reason. “I think 2024 has been identified as a year of a big push by the Russians,” says one official who has been monitoring foreign interference issues for several years. “The American elections are the highlight – and everything else serves as a rehearsal,” is his assessment. “Everything else” includes, therefore, the European elections in June and the Olympic Games in Paris this summer.

Among the concerns hanging over these elections are a possible data leak, akin to the 'Macron Leaks' in 2017; and also any Euro MPs who are a bit too naive over befriending foreign agents. To stay ahead of the game, a discreet meeting was held on March 29th at the SGDSN headquarters.

All French parties fielding lists for the European elections were invited to this gathering. Seventeen (out of twenty-two) accepted the invitation, including all the major parties. Various government services, including the DGSI, came to “brief” them on ways to secure their data and communications. Messages conveyed to participants included activating two-factor authentication to access their emails or social networks, ensuring their servers have undergone security updates, adopting good password practice, and separating personal from professional use by not using their own phones to manage party affairs.

To show that the threat was real, the security services showed the party representatives at the gathering a mundane message sent via Gmail. In reality, it was the phishing scam that ensnared former Hillary Clinton presidential campaign manager John Podesta. By clicking on it in error, Podesta was responsible for the leaking of 20,000 pages of emails and a state scandal.

Counter-espionage professionals also advised future MEPs to be vigilant about their encounters in the coming weeks. “There are people who think that being able to spy on a future Member of the European Parliament could be of use,” noted senior public official Stéphane Bouillon, secretary-general for defence and national security, during a recent hearing by MPs. A blunter version of the advice came from a source involved in the gathering. “We explained to them that if a Russian diplomat offers them a gold pen, they shouldn't keep it,” the source explained.

Some believe that the risks involved should probably be spelled out on a wider and more systematic basis, including within the French Parliament itself. For despite the current situation there is “no specific awareness campaign for elected officials at the moment”, confides a member of the National Assembly's Defence Committee. Even for members of this particularly sensitive committee, such training is not mandatory. “There are indeed training sessions with the DGSI, but they are voluntary,” the committee member says.

Diplomacy or electoral strategy?

The shift in French attitude towards Moscow does raises some questions. “Are other actors also using these [influence] methods? Clearly. But the Russian escalation is such that we judged that the only way to contain it was through public exposure. Whereas with others, the possibility of diplomatic discussion is always open,” explains the Ministry of Foreign Affairs.

In other words: when China targets French interests, it is always possible to discuss it one-on-one. With Russia, all dialogue is broken off. But is this simply diplomacy, or also electoral strategy? By constantly highlighting the wrongdoings of the Russian government, is Emmanuel Macron not deliberately and strongly emphasizing an issue seen as likely to weaken his designated opponent for the European elections, Rassemblement National? The president has long wielded this line of attack against Marine Le Pen's far-right party.

As for the laws passed to prevent foreign interference, some complain that they pose risks to public freedoms. “I wonder if the real trap the Russians are setting for us isn't to get us to further tighten our laws, to further restrict our freedoms, all in the name of defending ourselves,” wonders Éric Bothorel, an MP for the ruling Renaissance party and a digital expert. “We must not take this possibility lightly.”

------------------------------------------------------------------------------

- The original French version of this article can be found here.

English version by Michael Streeter