In the beginning was the frog. On July 26th 2012 Christian Herrault, deputy general operating manager at the world's leading cement firm, French multinational Lafarge, sent an email to two members of staff. In the email's subject line was the word “Syria”. These were desperate times in that country. It had fallen into civil war and the French embassy had closed its doors in the Syrian capital Damascus some five months earlier.

At the time a number of crucial questions were being asked at the Paris headquarters of Lafarge, whose cement factory in Syria was the largest and most expensive in the Middle East?. Should the company stay or, as the French oil giant Total had decided to do at the end of 2011, up sticks and leave? “I need to understand … because I wouldn't want us to be like the frog in the saucepan which heats up slowly but surely, the frog that can no longer jump,” wrote Christian Herrault, who was also chair of the board for the Syrian company that ran the cement plant.

In the end Lafarge kept the plant open, at terrible cost. Two years after Christian Herrault's email, the company that was set up at the start of the 19th century on the chalky soils of the Ardèche in south-east France by the Pavin de Lafrage family, the very model of paternalistic capitalism imbued with Christian values, seemed to have become exactly what the company feared it might. In other words, it had become the frog in the pan of water which, according to the fable, dies because it gets used to the slowing warming water and eventually boils to death. How had the company reached this point? It had done so by having a pact with Islamic State in Syria (also known as ISIS or Daesh) to ensure that its cement plant kept working, whatever the cost.

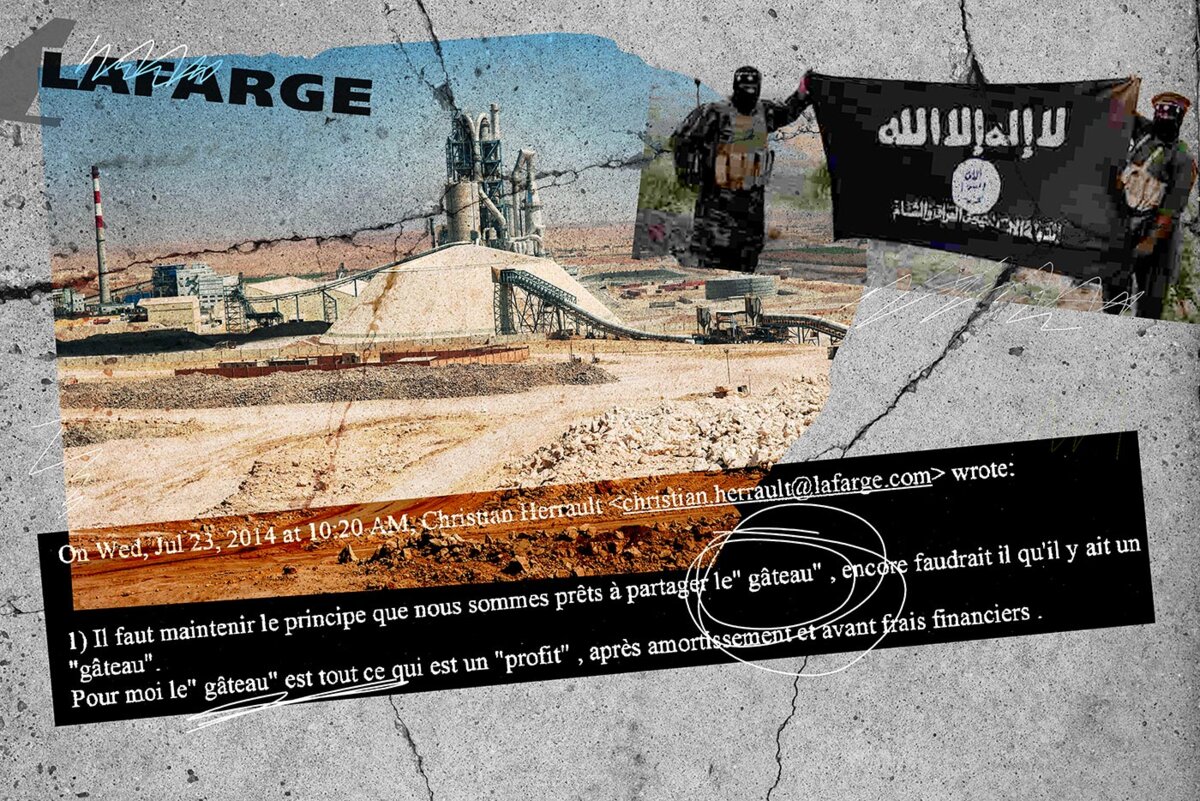

Enlargement : Illustration 1

“Herrault's story concerning Syria summed up the entire story of the group in this affair,” wrote an official from French customs, a member of its financial investigations team the Service d’Enquêtes Judiciaires des Finances (SEJF), years later in a summary report that Mediapart has seen.

This 62-page document, dated the end of November 2020, states that “Lafarge's executives had become used to an environment which was progressively getting worse to the point where it put at peril the existence of the company and of the entire group … Thus within the space of two years, the Lafarge management had gone from natural suspicion about the risks involved in a country that was at war and under the heel of armed groups, to making Daesh a supplier like any other, whose services had an impact on the sale price of cement and which ate into the company's profit margins.”

The report continued: “With the factory surrounded by Daesh, with all diplomatic services closed down, amid huge risks on the roads, with all airports out of use, and with the border posts on the Turkish frontier regularly closed, the production of cement … still continued and Lafarge was paying terrorists to protect the industrial site.” The investigations carried out by the customs department's SEJF, plus the work of two examining magistrates, led to Lafarge being placed under formal investigation for “complicity in crimes against humanity” - the first time anywhere in the world this had happened to a company – with several of its executives facing a probe for “financing terrorism”.

Lafarge made Daesh a supplier like any other, whose services had an impact on the sale price of cement.

In French law anyone who is placed under investigation benefits from a presumption of innocence.

If one had to chose just one document out of the tens of thousands of documents gathered by investigators to sum up this unique story, it would be another email from Christian Herrault, this one dating from July 2014. It discussed relations between Lafarge and Islamic state in terms that could not be clearer: “We have to maintain the principle that we're ready to share the 'cake' and, what's more, we have to ensure that there is a 'cake'. For me the 'cake' is anything which is a profit.”

This spells out in black and white what French investigators think was the motive for the alleged crime – greed. It was this lure of profit which brought down the last remaining moral barriers. It was what one customs official described in the SEJF report as Lafarge's “survival instinct”.

Contacted by Mediapart via his lawyer, Christian Herrault declined to comment.

According to the SEJF investigation, Lafarge's compromising behaviour in Syria involved numerous financial services which directly or indirectly benefited the terrorist organisations in situ. These included security payments, tax on suppliers, tolls, and the payment of intermediaries close to the Islamists. But one question keeps dogging those who have been close to the case for years: how much money did Lafarge pay to terrorist organisations in Syria in exchange for maintaining its activities there?

A report by firms Baker McKenzie and PricewaterhouseCoopers, commissioned after Lafarge merged with the Swiss company Holcim, as well as several press revelations (in Zaman al-Wasl, Intelligence Online and Le Monde) have put the total sum paid out at more than 15 million euros. This figure is strongly disputed by several of those under suspicion. According to a report written in September 2020, Lafarge's funding of Islamic State alone could, at the upper range of estimates, have reached 10.3 million euros, with the lowest estimate being 4.8 million euros. This does not include payments to other terrorist groups.

A collective decision?

To understand the multinational's downwards spiral - the group recently agreed to plead guilty in the United States and pay a fine of 778 million dollars to avoid a trial - one has to go back 16 years. To the end of 2007 to be precise, when the French giant paid 8.8 billion euros to buy the Egyptian company Orascom Cement, a subsidiary of the family-run group Sawiris, which includes Egypt's richest man Nassef Sawiris.

This acquisition, which was the first major act under the new Lafarge chairman and CEO, Bruno Lafont, who had taken up his position a few weeks earlier, was aimed at enabling the group to capture a greater market share in the region, especially in Syria.

As a result, between 2008 and 2010 Lafarge oversaw the construction of a massive factory in the north of Syria, close to the Turkish border. The size of the investment was in line with the scale of the group's new ambitions: some 680 million dollars, financed by 16 different banks (from Lebanon, Syria and Jordan) and also the European Investment Bank, France's Agence Française de Développement, a Danish fund and the group's own resources. The projections for this new factory, to be controlled and run from France, delighted Lafarge's shareholders. More than two million tons of concrete was due to be produced each year, with potential revenues estimated at up to 200 million euros.

“The hope for a profitable factory was there but the war shattered the new company's ambitions,” said the customs official in the summary report. Having plunged into civil war, in March 2013 Syria became the land of jihad, with the town of Raqqa falling into the hands of different rebel Islamist groups, Ahrar al-Sham and Jabhat al-Nusra. A month later Islamic State (IS), which had been created in Iraq, also arrived in Syria where it recruited members from al-Nusra. Some of the latter's senior figures refused to ally themselves with IS, and pledged allegiance to Al Qaeda.

In June 2013 the European Council – part of the executive arm of the European Union – placed Islamic State and Jabhat al-Nusra on the list of terrorist organisations with whom all relations are forbidden. That did not stop Lafarge and its directors in Syria, Bruno Pescheux and then Frédéric Jolibois, both of them now under investigation, from overseeing negotiations between the company and terrorists. According to the judicial investigation, though by the end of June 2013 the Islamists had stepped up the number of roadblocks of lorries, checkpoints and ransom demands, emails from Lafarge pointed to “good relations with Al-Nusra”.

According to the customs investigation summary, Lafarge headquarters knew at that time about the “terrorist nature of Jabhat al-Nusra, affiliated to Al Qaeda”. The report said: “The Syrian company was negotiating with this armed group in order to be able to continue to operate the factory.” It added: “An identical scenario was to take place again with Daesh.”

I had a long discussion with the Islamic soldiers.

Once again, internal emails on this have been unearthed. They show that on one occasion the director of the Syrian factory asked one of the group's intermediaries in the area to “sort the ISIS problem”. On another occasion he “didn't hesitate to order raw materials from quarries under Daesh control”.

“Bruno Pescheux [editor's note, the factory director from 2008 to 2014] knew that he was financing a terrorist group named Daesh but he had the approval of his superiors ... who were aware of everything … He simply regretted not having raised the alarm more forcibly,” said the customs officials in their report.

At the end of September 2013, moreover, an agreement was reached between Lafarge and the terrorists, following which cement sales increased again. “But the ISIS accord had to be renegotiated on several occasions, in October 2013, in November, in April 2014, in July and in August,” said the SEJF customs report. It added: “The negotiations continued even after the vote and publication of UN resolution 2170 on August 15th 2014 banning all links with ISIS.”

Contacted by Mediapart the first director of Lafarge's Syrian factory, Bruno Pescheux, did not respond. His successor Frédéric Jolibois “strongly disputed the incriminating aspects in the summary report”, according to his lawyer Jean Reinhart. “The rest of the investigation has shown the particularly complex nature of this case in which Frédéric Jolibois did not have authority and control over financial relations with the different intermediaries,” the lawyer added.

According to customs investigators, the people in charge at Lafarge in Paris were aware of this UN resolution. “However, after some questioning, all of them approved the new accord with ISIS,” says the SEJF report, which underlined that “the nature of ISIS was known about”. It said: “Thus genuine commercial negotiations were carried out with ISIS.”

Some of the documents collected by the investigators seem to suggest the French multinational was being completely cynical in its approach. For example, there are minutes of a meeting in 2014 quoting the comments of a manager, who was in charge of internal monitoring, about Syrian cement sales for April that year. They said: “I had a long discussion with the Islamic soldiers and we carried out a lot of market research and they would be happy to supply fuel, tyres and pozzolan at an attractive rate and no one could argue with their prices.”

Role of the French secret services

Just how far up did responsibility lie at Lafarge for its Syrian failure? According to the judicial investigation, it went right to the top. Two people in particular have attracted the investigators' attention in addition to snail email man Christian Herrault, the deputy general operating manager. One is Jean-Claude Veillard, who was the director of security at the time the events occurred, and Bruno Lafont, the former group chairman and chief executive officer.

The former, whose links with the far-right Front National were reported by Mediapart in 2017, is a former and much-decorated military officer. Very early on he was one of the rare voices expressing incomprehension at the fact that the Syrian cement plant was continuing to operate when all other French companies were abandoning the region because of the risks involved. “It's undeniable that from 2012 Veillard was not enthusiastic about maintaining the operation in Syria,” says the customs report. However, it goes on to note that “despite reservations about relations with al-Nusra, about payments to Daesh, about business activity continuing, not only did he not stand by his position, he helped operations staff ...to go against his own convictions”.

The case of Jean-Claude Veillard, who is under investigation for “financing terrorism”, is made even more interesting by the fact that because of his job it was he who was the link between the company and the French intelligence services. He was, quite naturally, in touch with them as the head of security in a group that was operating in a country such as Syria. The numerous documents seized during searches have enabled investigators to chart the extent of those relations, and the number of meetings he had during this period with several different services: the military intelligence agency the Direction du Renseignement Militaire (DRM), the external intelligence agency the Direction Générale de la Sécurité Extérieure (DGSE) and the latter's domestic counterpart the DGSI.

The intelligence services acted opportunistically and made the most of this chance to have eyes and ears in an area … abandoned by Westerners.

According to the investigation, there is no doubt that the secret services had been informed about what was happening in Syria around the Lafarge factory, as reported in several press articles, notably in Libération. But there is nothing to suggest that these agencies, and the French state itself, asked the company to stay there.

“Jean-Claude Veillard was loyal to his employer and understood the operations staff who wanted to carry on despite everything. At the same time he was loyal to France by giving all the intelligence gathered to the state intelligence services who fight against terrorism: the DRM, DGSI and DGSE. They had made requests without giving any encouragement to stay,” said the customs report.

In a report in 2019, which specifically dealt with relations between the group's security director and the secret services, investigators concluded that “Jean-Claude Veillard did his job very well and clearly supplied extremely precious information to the different intelligence services during the period 2012 to 2015”. These agencies had been interested in lots of different information: about daily life in the area, knowledge of communications links, what the Assad regime was doing, the movements of armed groups and information about the political mood. However, the report stated that “at no time did it seem that these services had asked Lafarge to stay in Syria. They acted opportunistically and made the most of this chance to have eyes and ears in an area which had been abandoned by Westerners.”

A former DGSE agent, Pierre M., who spent 14 years from 2002 to 2016 at the agency before himself joining Lafarge, recalled that during the Syrian affair there had indeed been exchanges with Veillard, who had been a “useful contact”. But he “never saw a document and never attended a meeting” where there was any question of asking Lafarge to stay. “The DGSE doesn't have the authority to do so,” he said when questioned as part of the investigation.

In a written statement for the defence, Jean-Claude Veillard's lawyer Sébastien Schapira highlighted what he called “errors” and “bias” on the part of the SEJF customs investigators in their account of events. And he accused them of “manipulating incriminating comments” and of “truncating” and even “distorting” those comments that support the defence case.

“Jean-Claude Veillard was constantly opposed to any form of negotiation with armed terrorist groups, from the moment his advice was sought. He never gave any help or advice to any operations staff in order to carry out direct or indirect payments,” wrote Sébastien Schapira. The lawyer pointed to his client's “lack of decision-making authority” at Lafarge and the “absence of positive acts” by him in relation to the accusations. He said that no document showed the “slightest agreement” or “encouragement” for payments to the terrorists to take place, contrary to what the accusations suggested. In summary, the lawyer said he knew about it, but that was not a crime in itself.

The other key figure is the man who was head of the group at the time of the Syrian fiasco: Bruno Lafont. He joined the company in 1983 at the age of 27 and became CEO in 2007. During the investigation his line of defence was that he did not know what went on, saying “I don't do my staff's work.” But the customs investigation report says: “This posture of a boss above the fray, who was only interested in grand visions of a group present in 65 countries, was an illusion. Bruno Lafont knew the cement works in every country down to the smallest detail … including Syria.” This was clear from “numerous documents”, according to the investigation.

However, Bruno Lafont's lawyer Céline Lasek told Mediapart: “These phrases come from a police summary report dating from 2020. To give credence to a summary that publishes assessments contradicted by others and to an out of context extract from [questioning in] custody seems to us to be, at the very least, questionable. The drip feed use of extracts from statements in 2020 or older, obtained in a curious manner, contribute nothing to the understanding of a complex case with multiple dimensions.”

Renowned as a man with a secretive nature, Bruno Lafont is described by several former members of staff as an elusive character, which inevitably gives rise to speculation as to how to understand the motive behind behaviour that ultimately, the judges suspect, propelled him into a devil's pact with terrorists.

According to a former finance director at the group, who was questioned during the investigation as a witness, the explanation is both psychological and purely economic. From a psychological perspective, the Syrian factory was, said the witness, Bruno Lafont's “first big success after taking over as chairman”. And “anything which might overshadow the soundness of this acquisition led him to react strongly and to express his anger”. From an economic perspective, the witness said that: “Mr Lafont had performance-related obligations which led him to challenge anything that might lead to risking the company's economic performance, its profits.”

During a recent interview with Libération, Bruno Lafont tried to shift responsibility for the saga elsewhere. “The authorities, at the very least, encouraged us to maintain our operations in Syria. But when I say us, it wasn't me, it was my staff who were in contact with them, with the ambassadors and the other administrations,” he said. He did not spell out what he meant by the term “the authorities”, while the investigation has meanwhile reached the opposite conclusion about the actions of the intelligence services.

On May 10th the court of appeal in Paris is due to hear an appeal over procedural issues in the case; on September 19th the decision to place Lafarge under investigation for “complicity in crimes against humanity” will be considered by the criminal division of the country's top appeal court, the Cour de Cassation.

-------------------------

- The original French version of this article can be found here.

English version by Michael Streeter

-------------------------

If you have information of public interest you would like to pass on to Mediapart for investigation you can contact us at this email address: enquete@mediapart.fr. If you wish to send us documents for our scrutiny via our highly secure platform SecureDrop please go to this page.

-------------------------