Many motorists think that it costs too much to repair their cars. But they were unaware of the full extent of it. For from the end of the 2000s, the French car makers Renault and PSA Peugeot Citroën effected an overall hike of 15% on the price of those spare parts over which they have a monopoly. That is revealed in confidential documents produced by management consultancy firm Accenture and obtained by Mediapart. These were shared with the European Investigative Collaborations (EIC) network and the Belgian daily newspaper De Standaard as part of this CarLeaks investigation.

Enlargement : Illustration 1

The practice was carried out thanks to highly-sophisticated software supplied by Accenture to the French car manufacturers which allowed them to put up prices in a way that was almost undetectable. According to the documents, the operation brought in more than 100 million euros a year in extra profits to each car maker. As a result, Renault and PSA have extracted an additional 1.5 billion euros or so from motorists around the world over a period of nearly ten years.

Though it may be considered shocking on an ethical level, the scheme also raises legal issues. The documents that reveal the practice come from a civil court case at the commercial court in Paris brought by the software's inventor Laurent Boutboul. Claiming he was wronged by Accenture during the sale of his own company to them in 2010, he today accuses the management consultancy firm, Renault and PSA of having used his system to coordinate a rise in prices, in breach of competition rules.

Enlargement : Illustration 2

Contacted by Mediapart, Boutboul confirmed via his lawyer Franck Normandin the existence of the civil proceedings but refused to comment on “confidential information discussed in the context of ongoing judicial proceedings”. Laurent Boutboul simply stated that “this litigation concerns the commitments of the American group Accenture and its French subsidiary to respect the rules of an antitrust protocol, defined before the acquisition of my company Acceria to ensure the lawful use of the process that I designed”.

Having been alerted to these practices last year the French competition authority, the Autorité Française de la Concurrence, immediately opened an investigation but then closed it after several months without carrying out further investigations or questioning potential witnesses. Contacted by Mediapart, the authority said that the “information brought to its attention” did not justify the opening of an “in-depth investigation” but that it reserved the possibility of doing so if “new information” was provided to it.

Accenture and PSA Peugeot Citroën refused to speak to Mediapart and simply sent short written responses. Accenture says that Mediapart's information “contains numerous inaccuracies and errors of interpretation” and that the firm respects its “legal and contractual obligations”.

PSA says it “completely contests” these “unfounded accusation” without going into more detail. In its written response Renault said that it had “not engaged in any coordination, of any form whatsoever, with PSA” and had never “pursued any approach which could, directly or indirectly, pertain to a breach of competition rules”.

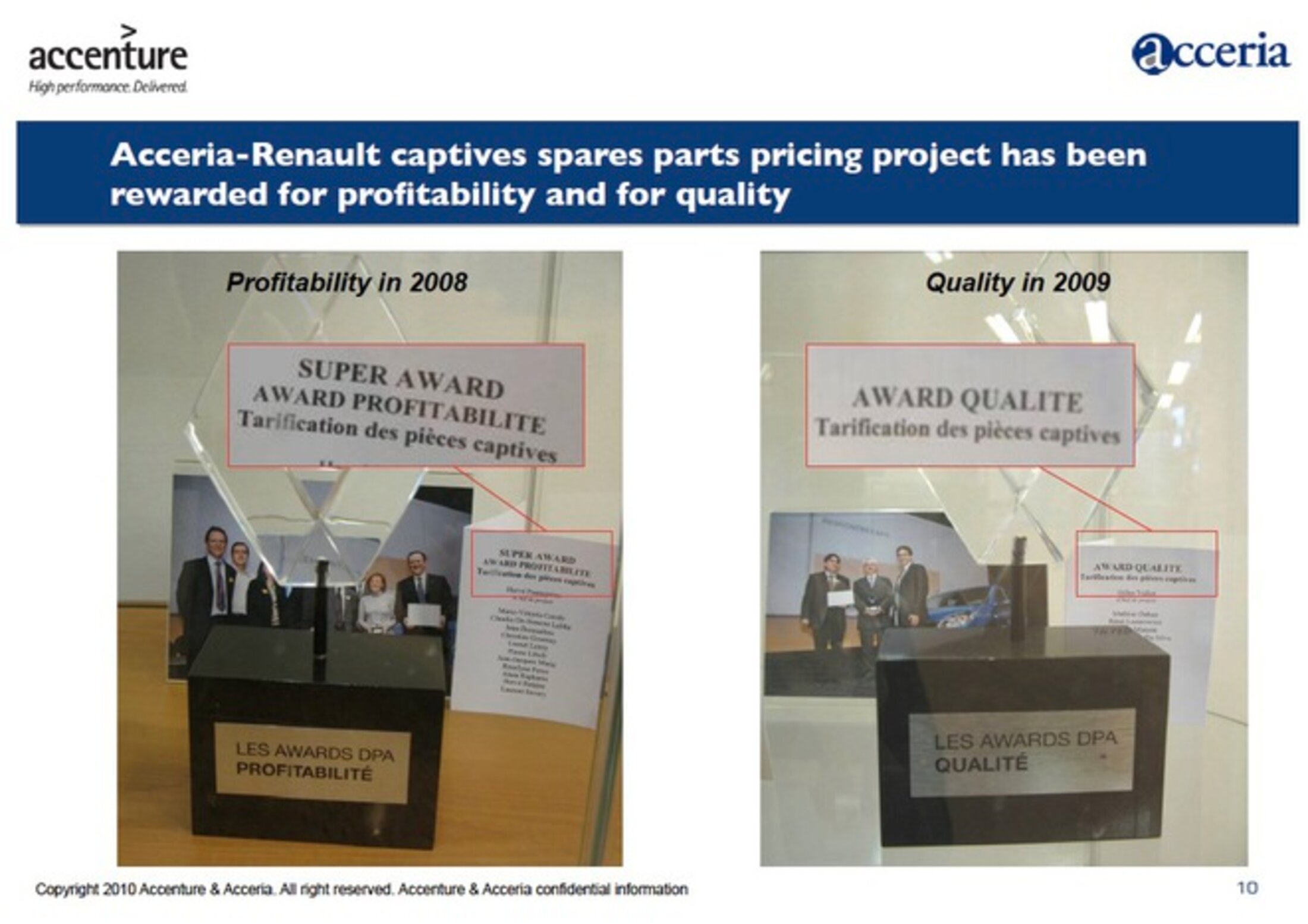

The practices carried out by Renault and PSA are all the more shocking because of the fact that even before the implementation of the Accenture software they were already selling their spare parts at exorbitant prices. According to the confidential documents seen by Mediapart, they were selling parts for up to five times the price they paid for them, a profit margin of up to 80%. According to Accenture, spare parts make up “9 to 13% of turnover” for the car manufacturers but “up to 50% of their net profits”.

These enormous profits are mostly generated by so-called “captive” parts over which there is no or very little competition, meaning the motorists who need to repair their cars have very little choice but to buy them. On average these “captive” parts make up 30% to 50% of the manufacturers' total spare parts, and far more in France. For France is one of the last seven members of the European Union which continues to grant a monopoly to car makers over what are called “visible” parts, in other words bodywork parts – bumpers, radiator grills, rear-view and wing mirrors, car wings and so on.

For nearly ten years consumer groups such as UFC-Que Choisir, garage owners and independent parts distributors have fought to try and put an end to this “French exception” on bodywork parts and to the “unjustifiable prices” borne by motorists. But they have failed.

Enlargement : Illustration 3

In 2015 an amendment to this effect was proposed to the so-called 'loi Macron'. But Emmanuel Macron, then the economy minister, refused to accept it and echoed the arguments used by the car manufacturers. “I have intellectual sympathy for the amendment,” he told France's National Assembly. “But the concrete consequences don't make its adoption reasonable, with regard to the network's economic situation.”

Meanwhile, thanks to the software supplied by Accenture, the French car manufacturers carried on raising their profit margins. In view of the monopoly on bodywork parts and the fact that Renault and PSA Peugeot Citroën account for 55% of car sales in France, it is French motorists who are the biggest victims of the system.

The saga began in 2006 when Laurent Boutboul, a consultant and expert in optimising industrial profits, set up a company called Acceria to market a software called Partneo that he was in the process of developing. The company approached Renault with a tempting proposition: that though the price of “captive” parts was already high, it was possible to increase them still further.

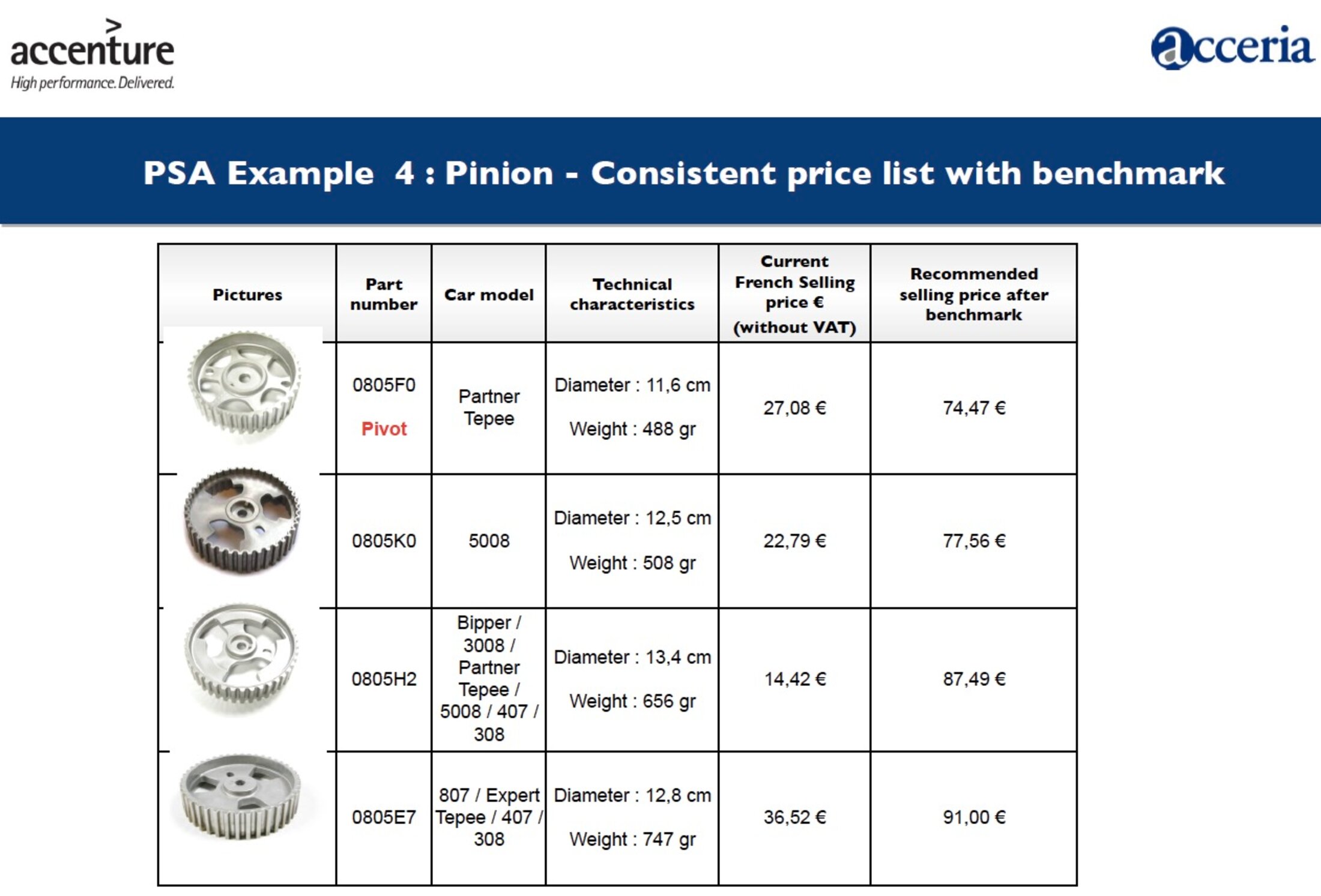

At the time the car manufacturers fixed the price of their parts on the basis of their cost, multiplying the cost price by a set ratio. Partneo changed this approach completely by basing the price on the “perceived value” of a part, in other words the maximum price that a customer is psychologically prepared to pay.

A wheel arch cover costing €3 that sells for 25 times that amount

How it works is that the parts are weighed, measured, photographed and analysed in a warehouse laboratory in order to create a database. Thanks to sophisticated algorithms the price of similar parts are then increased according to the price of the most expensive component in that 'family'. The majority of rises are between 20% and 300%. However, the prices do not appear as a shock to consumers as the components are all of similar size and appearance.

Enlargement : Illustration 4

Take the example of Renault's accelerator pedal sensors. The one for its Espace IV model costs 12.60 euros and was resold for 109 euros, nearly nine times dearer. Yet the sensor for the Mégane, which has a similar cost price, was sold for 'just' 51 euros. Thanks to Partneo, the price of the Mégane sensor more than doubled in the space of a few years, to reach 110 euros, while the Espace IV sensor's price increased by only 2% to 112 euros.

The documents obtained by Mediapart show other massive increases too. The mirror on a Renault Clio III, which cost 10 euros and which was already being sold for nearly eight times that amount at 79 euros, saw its price double to 165 euros after the Partneo software was used. Meanwhile the wheel arch cover for a Dacia Logan and a Dacia Sandero – Dacia is Renault's low-cost brand – which cost 3 euros and was sold for 21 euros saw its price jump to 76 euros. That was an increase of 264% and represents a final sale price which is 25 times the cost price.

The software is also designed to conceal the overall rise in prices. Partneo increases the prices of around 70% of the parts – generally the most popular – reduces them on 20% of them and leaves the remaining 10% unchanged. Given the number of parts that are involved, which can come to several tens of thousands per manufacturer, and the variations in the prices, it is impossible to see what is going on. The software can also be set so that it only gives moderate rises to those components that are 'monitored' and used to make up the price index compiled by car insurers through their organisation the Sécurité et Réparation Automobile (SRA).

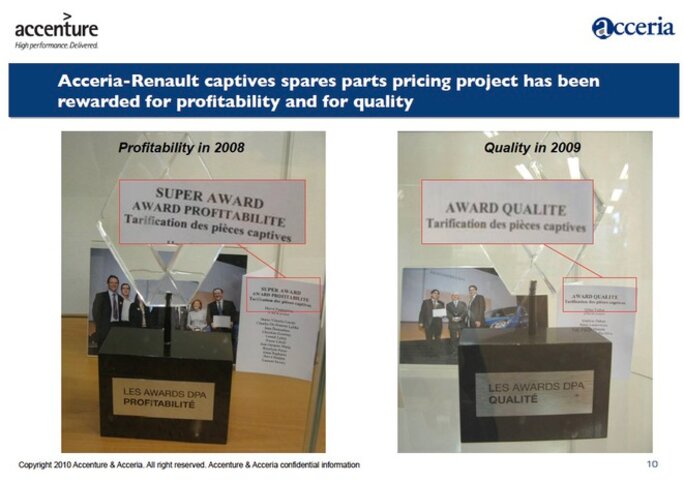

Renault were impressed enough order the software. The results were so spectacular that in 2008 the operation received an internal “super award” for being the most profitable company initiative of the year (see below). Renault told Mediapart that the team which received this price had worked on the “captive” parts market since 1992, “thus well before the use of Partneo”.

Enlargement : Illustration 5

According to figures contained in Accenture's documents, the Partneo software enabled Renault to increase the price of its captive parts by an average of 15%, which earns it an additional 102 million euros a year. In total that means the company has so far raked in an extra 800 million euros in all, directly from the pockets of consumers. Renault has responded saying that these figures “don't correspondent to the data [it has], and which is by its nature confidential”.

Up to this point, while the practice was ethically questionable, it was perfectly legal. The situation became more risky legally when the software was used with a second car manufacturer. In 2009 Accenture signed a commercial partnership with Acceria and then bought the company the following year. Now that Accenture was in control it looked elsewhere for business and naturally turned towards the other major French manufacturer PSA Peugeot Citroën. The methods used, however, were problematic.

On December 17th, 2009, a sales executive at Accenture wrote to one of the managers involved with spare parts at PSA. He promised a rise in prices of between 10% and 20%, representing 70 million to 140 million euros extra revenue a year. “As mentioned during our previous meetings, these ratios come from recent experiences with some generalist automobile manufacturers,” he wrote.

The problem was that Accenture revealed that its previous client was Renault. In a commercial presentation carried out for PSA at the start of 2010 the management consultancy indicated that its project with Renault had received a “super award” for profitability. They even showed a photograph of it. The documents obtained by Mediapart show that Accenture also supplied PSA with examples of parts whose price had been optimised, using Renault items. Accenture says that it “does not exchange sensitive and/or confidential information between its clients”.

However, the consultancy's defence conflicts with the written evidence of a former Acceria employee, which was deposed with the civil legal proceedings. He said that PSA executives had a “doubt as to the potential benefits” and “wanted to be reassured … by speaking to a client who had carried out a similar operation in the past”. Later the head of the sales team for the product at Accenture is said to have proposed to the head of the project at PSA that he meet his Renault counterpart. According to this witness shortly afterwards a PSA executive “informed us that he was going to start the project with Accenture and had confirmed to us that [the head of the project at PSA] had indeed contacted [his counterpart at Renault] and that he'd had very positive feedback”.

By coincidence, a confidential Accenture document shows that, thanks to the Partneo software, PSA ended up achieving an average rise of 15% across its 'captive' spare parts – exactly the same level as Renault. That brought in an extra 110 million euros a year for PSA, totalling 675 millions in all globally since it was introduced. In fact PSA won on two fronts as it increased its prices at the same time as the real cost of parts fell (see document below). The result was that between 2010 and December 2012 the average profit margin rose from 80% to 85% . This means that on average PSA was selling its spare parts for seven times the cost price.

Enlargement : Illustration 6

Renault categorically denies that it exchanged any information, pointing out that the “contact” with PSA described by the witness “was never organised” or taken up. The car maker added that it did not take part in “any coordination” with PSA and that it is “not in a position to assess the change in prices carried out by PSA”. Accenture and PSA also deny that there was any coordination, without responding precisely as to the existence of any “contact” between the two manufacturers.

'It is this use of data from competitors that I am concerned about'

In any case, Accenture seems to have breached its own rules. In the summer of 2010, a few months after the project started at PSA, the consultancy bought Acceria. After the software had been examined, Anthony Rice, Accenture's legal counsel based in London, was worried. On June 7th, 2010, he wrote that “Accenture believes that there are competition law risks” linked to Partneo; and that its “pricing solutions may be identified as a facilitating practice if two or more competitors adopt similar rates or pricing strategies” thanks to the software.

A month later, on July 23rd, in an email marked 'IMPORTANT: Acceria - business protocols' Anthony Rice sent to the Accenture teams involved with Partneo a “set of protocols” which he said “must be followed by each individual supporting the business”.

This protocols document set out a series of stringent rules on how Partneo was to be used. The Accenture consultants were forbidden to “disclose or share any non-public, competitively sensitive information obtained from one customer with another customer”, to “disclose any information that specifically identifies an individual company”, to use any “non-public, competitively sensitive information obtained from one customer to set the pricing of a competing company” or to “use the same pricing formula or solution to develop recommended pricing for competing customers”.

According to Mediapart's information, the two Accenture executives who took over as head of Acceria after the purchase made a personal commitment to apply the rules. “I confirm that I have read and understood the protocols,” the new director general of Acceria wrote on July 28th, 2010.

But according to two former Accenture consultants these anti-trust protocols were never shown to the teams in charge of the Partneo software. And as has been seen, some of their principles appear not to have been respected in relation to PSA.

Enlargement : Illustration 7

That indeed is what a former consultant at Accenture who was in charge of Partneo confirms. In 2015, when he was still in post at the consultancy firm, he discovered the existence of the anti-trust protocols. He alerted Peter Malone, who was in charge of ethics and compliance at Accenture, and Sean Duffy, who was legal counsel in charge of competition law.

In his email sent on June 18th, 2015, this consultant said that Accenture had revealed tp PSA “tariff levels...including [those of] Renault-Nissan...explicitly in 2010 and implicitly [there]after”. According to him, the consultancy firm had “reported to PSA that Renault used the same algorithms and formulas of prices definition offered to PSA” and that Accenture's intervention had “enabled PSA to increase its prices in proportions similar to those of Renault”.

The consultant concluded in a follow-up email on July 6th that “non-public information, among others from Renault, have been used in the setting process of PSA pricing rules. It is this use of data from competitors that I am concerned about.”

Accenture did not respond specifically on this issue but said that it had respected its “legal and contractual obligations”.

This evidence was deposed as part of the civil proceedings launched by the software's creator Laurent Boutboul at the Paris commercial court in November 2016 against Accenture, and then Renault and PSA. To support his claims about a possible agreement on prices, he commissioned a report from one of the most eminent French specialists on the issue, Emmanuelle Claudel, an associate professor in competition law at the Paris II-Panthéon-Assas university.

Her 46-page report's conclusions are very clear. While the operation in place does not constitute a classic cartel where manufacturers fix the prices together, she said the documents in the court proceedings that relate to the use made of Partneo seem to show a “concerted practice” that was anti-competitive in nature and one which sought to “coordinate strategies for raising prices”.

“The information transmitted … which needs to be supplemented, therefore allows one to reasonably suspect the existence of a horizontal price agreement between the companies Renault and PSA as well as the company Accenture, in the capacity of facilitator,” concludes Emmanuelle Claudel. “Subject to the result of more advanced investigations, these companies thus seem to us to be exposed to a risk of significant penalties.”

The law professor adds that an “investigation merits being carried out” by the European Commission's Directorate-General for Competition given the “economic importance and sensitivity of the sector concerned (that of captive automobile spare parts) and the influence of the operators implicated”. As far as Mediapart is aware, the case has never been referred to Brussels.

As has been stated, the French competition authority was informed of the case in 2017 but quickly decided against taking it any further. In the past the authority has, however, been very critical about the state of competition in the French automobile spare parts sector. In a public pronuncement made on October 8th, 2012, it criticised the “significant rise in the price of spare parts and maintenance and repair services for vehicles” which had gone up by 55% between 2000 and 2011. Today we know that some of that was linked to Accenture's software. The authority also called for France to finally put an end to the monopoly of car manufacturers over “visible” bodywork parts, as Belgium, the United Kingdom, Italy, Spain and Holland had already done.

“France is the only European country where the price of spare parts has gone up over the last ten years,” said Bruno Lasserre, then president of the competition authority, at the time. Six years later, motorists who have to buy parts to repair their cars are still being milked by the manufacturers.

In a sign of just how sensitive this subject is, the French manufacturers did not want to make any comment on the rise in spare part prices and the huge profits linked to this business. PSA simply said that it supplied “spare parts responding to the needs of all customers, whatever their budget” while Renault wrote that the price of its parts “is calculated taking into account factors that Renault considers to be fair and equitable”.

-----------------------------------------------------------------------

If you have information of public interest you would like to pass on to Mediapart for investigation you can contact us at this email address: enquete@mediapart.fr. If you wish to send us documents for our scrutiny via our highly secure platform please go to https://www.frenchleaks.fr/ which is presented in both English and French.

----------------------------------------------------------------------

- The French version of this article can be found here.

English version by Michael Streeter