On April 14th this year Manhattan Wolves, a jihadist propaganda magazine, published its second issue. As the organisation MEMRI, a non-governmental body that monitors Islamic media, pointed out, this online magazine which supports Al Qaeda and which describes itself as a “guide for lone wolves in Crusader countries”, called on followers to kill police officers. The magazine also carried an announcement of a 60,000-dollar reward in bitcoin for the first person to kill a police officer in a Western country. The cover photograph is the rear view of a police officer during an operation to maintain law and order. That police operation is in France.

So when early on the afternoon of Friday Jamel Gorchane, a 36-year-old Tunisian, stabbed a female police administrative officer to death at the entrance of the police station at Rambouillet, south west of Paris, before being shot dead himself by police officers, investigators immediately turned their thoughts to that call to murder in Manhattan Wolves.

A source close to the case confirmed to Mediapart that detectives will check on computer equipment seized during searches of the homes of friends and relatives whether the terrorist looked at this new jihadist media before carrying out his attack. Initial investigations have not so far produced any compromising evidence.

Jamel Gorchane stabbed his victim in the neck while she was in the entrance of the station. This was a technique identical to that used by Bertrand Nzohabonayo who, on December 20th 2014, shouted “Allahu Akbar” (“God is Greatest” ) before wounding three police officers at Joué-lès-Tours in central France; he was then himself killed. This was the prelude to a wave of terrorist attacks that went on to hit France and which has so far claimed 264 lives in six years.

Among those victims are 12 members of the forces of law and order (police, gendarmes, administrative staff), while around 20 more have been seriously wounded. That figure does not include the three soldiers killed by Mohammed Merah in south-west France in March 2012.

In 2018 Mediapart revealed that the security services as a whole – if one includes soldiers – were increasingly being targeted by jihadists. Since the 2012 attack at Joué-lès-Tours there have been 17 attacks of this type recorded, according to the country's anti-terrorism prosecutor Jean-François Ricard, speaking at a press conference about the Rambouillet murder on Sunday April 25th 2021.

Even before the Rambouillet attack, France's domestic intelligence agency the DGSI had established that the security forces have been the main target in 40% of all terrorist attacks in France since 2013. This percentage includes successful attacks (where there were victims), failed attacks (where the terrorists failed in their mission) and foiled attacks (prevented by the actions of the state's security services).

Yet while Africa and Asia have become used to these kinds of attacks on local police and security forces, the rest of Europe has seen just a few in recent years; a jihadist killed two police officers in Liège in Belgium in May 2018, and another fatally stabbed a British police officer outside the Houses of Parliament in London in March 2017. But terrorists have mostly preferred other, more undefined targets, seeking to kill the greatest number of people using vehicles driven through crowded streets in Barcelona, Berlin and Stockholm. So how does one explain the phenomenon of so many attacks on French police, something the DGSI called in a report at the end of 2017 a “French exception”?

First of all we can discount from the analysis so-called “opportunistic” attacks. It was apparently because of a traffic jam caused by a road accident that terrorist Amédy Coulibaly deviated from his initial objective on January 8th 2015, and chose instead to kill uniformed police officer Clarissa Jean-Philippe in the south Paris suburb of Montrouge. The day before, the brothers Chérif and Saïd Kouachi had killed Franck Brinsolaro, who was protecting Charlie Hebdo editor Stéphane 'Charb' Charbonnier, and who was the final obstacle between them and the massacre of editorial staff at the satirical magazine's offices. Once back in the street the pair shot dead police officer Ahmed Merabet whom they suspected – wrongly – of having fired at them.

On March 23rd 2018 Radouane Lakdim ended his terrorist attack by stabbing to death gendarme Lieutenant-Colonel Arnaud Beltrame, who had swapped places with a hostage that the terrorist was holding at a supermarket at Trèbes in south-west France. A little earlier that morning Lakdim had opened fire on riot-squad police officers who were jogging in front of their barracks at nearby Carcassonne.

Yet on most of the occasions when members of the security forces have come under attack they had been singled out as the target. This can be seen in some of the attacks in Europe that were planned by Islamic State from their Iraqi-Syrian stronghold. In January 2015 members of the terrorist cell at Verviers in Belgium, led by Abdelhamid Abaaoud, were excited at the prospect of “getting a cop”. And the terrorists in the 'Ulysse' case – in which a DGSI officer went undercover – who in February were given jail terms ranging from 22 to 30 years, said they had been ordered to carry out an attack at the DGSI headquarters or at 36 Quai des Orfèvres, the address of the Paris police headquarters. “We had to go inside and open fire on whatever was there,” said one.

Enlargement : Illustration 1

There is also the example of the attack at Maganville north west of Paris in 2016. At around 8pm on June 13th of that year Larossi Abballa stabbed Jean-Baptiste Salvaing, the divisional inspector of a police unit at nearby Les Mureaux, seven times in the stomach, killing him in front of his home. He then holed himself up inside the police officer's home where, after the terrorist was finally killed, investigators found the body of Jean-Baptiste Salvaing's partner Jessica Schneider. She was herself an administrative official at the police station at nearby Mantes-la-Jolie.

The investigation, which is still ongoing, has not yet established any clear link between the killer and his victims. But what is clear is that Abballa did not attack them by chance. In a Facebook video claiming responsibility that was made at the victims' home, the terrorist boasted about his crimes and called on those watching to also “single out police officers”.

One other certainty is that Abballa's desire to target the police and security forces was not new. As Mediapart has revealed, from as early as 2011 he had been planning to “start wiping out unbelievers” and had a clear idea of how he would go about that: when his home was later searched investigators found a diary containing a list of police stations.

How Islamic State mocked France's state of emergency

During Sunday's press conference, prosecutor Jean-François Ricard pointed out how “as symbols of the state, the forces of law and order have for a long time been a preferred target for terrorists”. This is an obvious point. As Inspire, the Al Qaeda magazine in the Arabian peninsula, stated in May 2016 the choice of location for any planned attack should enable the perpetrator to “send a clear message”. What better way to attack a state than to attack its police and security forces?

Back in 2012 Mohammed Merah had told the police officers who took part in the siege against him: “I knew that by killing soldiers and Jews the message would be heard more loudly … I had a clear objective in my choice of victims.”

As essayist Hakim El Karoui, the co-author with Benjamin Hodayé of the book Les Militants du djihad. Portrait d’une génération, published by Fayard in December 2020, writes: “The jihadists attack representatives of the state, who moreover are the ones who are hunting them. By targeting the forces of law and order they are thus attacking both their operational and symbolic adversary. What is most surprising is not so much that they attack the French police but that there are not more terrorist attacks like this in other countries ...”

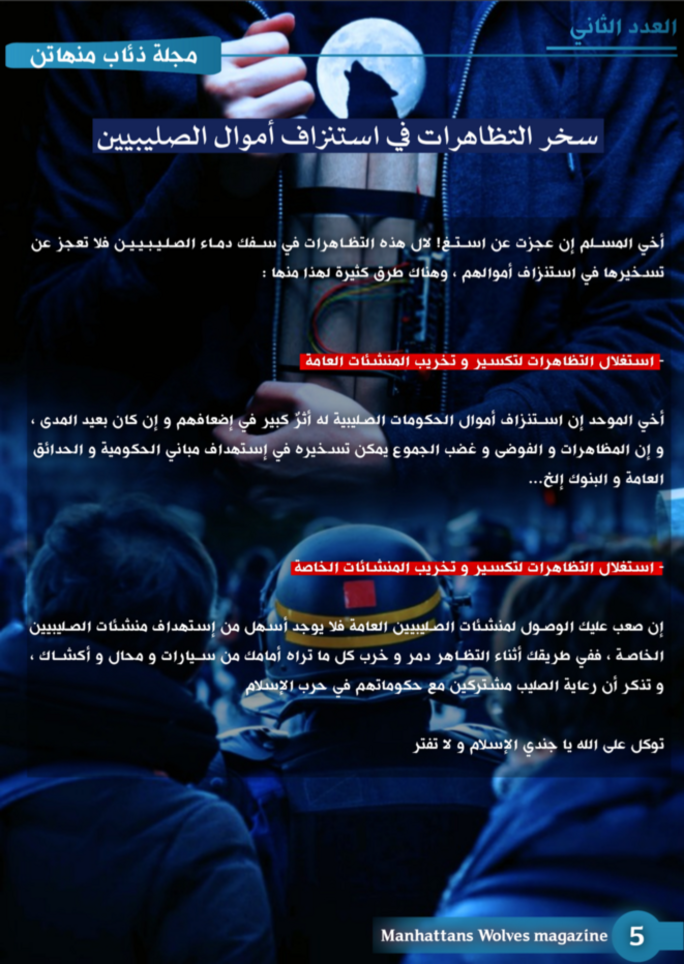

In one of his messages Islamic State's spokesperson Sheikh Abu Mohammed Al Adnani, who was killed in 2016, urged “believers in Western countries” to attack “their armies, their police, their intelligence services”. And Jihadist propaganda pays close attention to the actions and abuses carried out by its enemies' security and police forces.

An example of this came during France's state of emergency which was brought in after the November 2015 terrorist attacks. Searches carried out by investigators in the middle of the night under the provisions of this emergency legislation caused controversy in France and Islamic State was quick to react. Its French-language review, Dar al-Islam, jeered in an editorial: “The key measure of the French government to confront the [editor's note, the next terrorist attacks] is the state of emergency! Let's consider it for a moment. Completely arbitrary searches, counter-productive house arrests and mass surveillance which is heading towards totalitarian politics. In other words, completely the opposite of good, intelligent and targeted intelligence work.”

Enlargement : Illustration 2

From 2014 to 2018 senior civil servant Louis Gautier was secretary general of the inter-ministerial Secrétariat Général de la Défense et de la Sécurité Nationale (SGDSN), which answers to the prime minister and coordinates policy on national security issues. He draws a distinction between attacks planned by Islamic State which involve several terrorists and in which the aim is to “provoke shock, panic, by blindly attacking a place, a spectacular”, and those acts that are committed by lone individuals. “In these latter cases, attacking police officers, it's like with the killers of the priest at Saint-Étienne-du-Rouvray [editor's note, in Normandy in northern France], they don't need long speeches, the message is obvious.”

In fact, since the collapse of the Islamic State's Caliphate the number of attacks on police and security forces has increased. Thirteen of the 17 attacks mentioned by prosecutor Jean-François Ricard took place after 2017, by which time the terrorist organisation was no longer able to plan sophisticated attacks at long distance.

Over the last four years the majority of attacks against France have been carried out by lone individuals using a basic modus operandi that is known in intelligence service jargon as “low intensity”. This means they are mostly carried out using knives or other sharp instruments. In a confidential report in 2019 the domestic intelligence agency DGSI noted that these terrorists “prefer simple operating methods against vulnerable and/or symbolic targets such as the security forces”.

That was particularly the case in 2017. Out of eleven terrorists attacks carried out or attempted in that year, nine targeted the police or security forces. One was against the police officer Xavier Jugelé, who was killed on the Champs-Élysées in Paris; two colleagues were wounded. In other incidents a police patrol was attacked on the square in front of Notre-Dame Cathedral, and a gendarme's vehicle was rammed on the roundabout on the Champs-Élysées.

Soldiers deployed as part of Operation Sentinelle – designed to protect potential target sites from terrorists – were attacked on five occasions. One attack at Levallois-Perret north-west of Paris involved the driver of a rented BMW car running down soldiers, leaving six injured; soldiers guarding the Carrousel du Louvre – a mall next to the Louvre Museum – were attacked by a man with a machete; and there were also attacks at the Châtelet–Les Halles metro station in Paris and at the foot of the Eiffel Tower. And the 20 failed or thwarted attacks that had been planned further highlighted this trend; in most cases the would-be jihadists were planning to hit targets such as barracks, a police station, an army base or an air base.

The phenomenon continued less frequently but with grimmer impact in 2019. On October 3rd of that year Mickaël Harpon, an IT worker in the intelligence unit at police headquarters in Paris, the DRPP, stabbed to death three police officers and an administrative worker before being killed himself. On April 20th 2020 a man drove a car at three police motorcyclists at Colombes north west of Paris, injuring two of them. In a message found in his vehicle he pledged allegiance to Islamic State.

Enlargement : Illustration 3

Police and soldiers in uniform or leaving an easily identifiable location such as military barracks or a police station are an easy option for lone terrorists, who are not well organised and who in certain cases are fragile individuals, with some even suffering from psychiatric problems.

In September 2020 Zaheer Hassan Mahmoud used a meat cleaver to attack and seriously wound a man and a woman who worked for the press agency Premières Lignes, and who had the misfortune to be on a smoking break on rue Nicolas-Appert in Paris in front of the old Charlie Hebdo offices. The terrorist had intended to attack Charlie but was unaware that the editorial team of the satirical weekly had moved since they were attacked in January 2015 by the Kouachi brothers.

'You slit the throat of the first cop you come across. If they're a female Arab, that's the best'

The DGSI puts the fact that France suffers more of these attacks than other countries in the West down to a “combination of personal bitterness and ideological motivation”. Marc Hecker, a researcher at the security studies centre of the international research institute IFRI, who is about to publish with Élie Tenenbaum 'La Guerre de vingt ans' published by Robert-Laffont, notes that several attacks have been carried out by terrorists with a criminal past, where the “former criminal wants revenge against the institution”.

That is the case with a number of the individuals who have carried out terrorist attacks on French soil: from Amédy Coulibaly to Larossi Abballa and including Karim Cheurfi who on April 20th 2017 used a Kalashnikov rifle to kill police officer Xavier Jugelé as he sat in a police van parked on the Champs-Élysées. He had spent eleven years in jail for previously shooting at police officers, and in the month before the Champs-Élysées attack he expressed a desire to kill members of the police and security forces. According to the police anti-terrorism unit UCLAT, Karim Cheufi “vowed unswerving hatred of the forces of law and order”.

Enlargement : Illustration 4

Another factor to take into account is that within their world attacking police officers and soldiers portrays a jihadist in a glorious light; showing that they are indeed a warrior. Jihadist propaganda plays on this idea. The fifth issue of Dar al-Islam magazine declared that “death in combat is the most beautiful of deaths” and pointed to the “fine example of Mohammed Merah, Jérémie Louis-Sidney, Amédy Coulibaly”, terrorists who had all been shot dead by the French police.

Sentenced to 30 years in prison in July 2020, the jihadist Tyler Vilus admitted that he was preparing an attack when he was arrested in the summer of 2015 after returning to France from Syria. “I wanted to die with weapons in my hand. Not by killing people in a trap,” he said. “There are people who have an obsession with civilians. I'm not one of those. My focus was on the security forces.” Back in August 2013 Tyler Vilus incited people on social media to attack police and security forces in France. “You slit the throat of the first cop you come across. If they're an Arab that's better, and the best is a female Arab.”

For jihadists, attacking security forces has one final and not insignificant attraction: preparing them for after the attack. “As the forces of law and order are armed, the jihadist has more chance of being killed and of getting martyr status,” said Marc Hecker. “It's part of that logic of going to meet death yet without committing suicide.” Martyr status supposedly gives a person access to Paradise.

One of the three terrorists in the Ulysse case mentioned earlier, who said they had wanted to attack the DGSI's headquarters or the Paris police headquarters, admitted in custody: “The aim was to get killed by police officers or soldiers.”

-------------------------

If you have information of public interest you would like to pass on to Mediapart for investigation you can contact us at this email address: enquete@mediapart.fr. If you wish to send us documents for our scrutiny via our highly secure platform please go to https://www.frenchleaks.fr/ which is presented in both English and French.

-------------------------

- The original French version of this article can be found here.

English version by Michael Streeter